Jews in Istanbul Threatened, This Time by Public Advertisements

Special for the Armenian Weekly

A twin suicide bombing claimed by Islamic Jihad kills 22 people at the Neve Shalom synagogue in Istanbul in 1986.

“One day you wake up and see that the neighborhoods of Kurtulus and Ferikoy have been surrounded by anti-Semitic advertisements.”

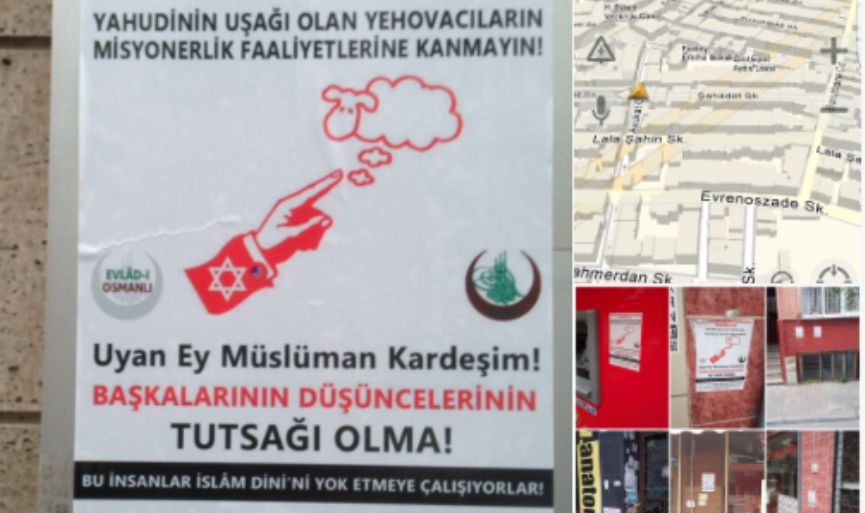

This is what Ishak Ibrahimzadeh, the leader of the Jewish community in Turkey, wrote on his Twitter account on Nov. 22. The advertisements he referred to read: “Do not be deceived by the missionary activities of the Jehovahists, who are the servants of the Jew. Wake up, hey my Muslim brother! Don’t be the captives of others’ opinions! These people are trying to destroy the religion of Islam.”

The advertisements also quoted the Koranic verse, which said: “Indeed, the religion in the sight of Allah is Islam.”

These words were what Jews were forced to see in these two Istanbul neighborhoods, which are in some of the most crowded parts of the city.

‘Do not be deceived by the missionary activities of the Jehovahists, who are the servants of the Jew. Wake up, hey my Muslim brother! Don’t be the captives of others’ opinions! These people are trying to destroy the religion of Islam.’

A similar sign at a shop in the Eminonu neighborhood of Istanbul greeted Jews in Sept. 2014. The sign read: “No Admittance to Jewish Dogs.” Many Jewish citizens of Turkey have shops in the neighborhood, according to the newspaper Salom.

Verbal attacks and insults targeting Jews in Turkey under the government of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) have been widely covered by Israeli media in recent years. But anti-Semitism is not peculiar to Turkish Islamists only. The independent scholar Rifat Bali wrote in an article published in 2009: “Anti-Semitism in Turkey is encountered not only among the Islamists and leftists but also among the nationalist and neo-nationalist streams, which in recent years have declared their hostility to the European Union, the United States, and Israel.”

Discrimination against and hate speech towards non-Muslims, including Jews, is a deeply rooted tradition in Turkey that goes back to the founding phase of the country.

Turkey has been secretly assigning codes its Armenian, Greek, Jewish, Syriac, and other non-Muslim minorities ever since the establishment of the Turkish republic in 1923. The Population Directorate of Turkey codes Greeks using the number 1, Armenians using the number 2 and Jews using the number 3.

When the Turkish republic was founded, non-Muslim bureaucrats and public employees—Turkish citizens of Jewish, Anatolian Greek, and Armenian origin—were quickly eliminated and banned from working for public institutions. Thousands of non-Muslims lost their jobs.

Like all non-Turkish languages, the public use of Ladino, or Judezmo, the language that Sephardic Jews brought to Ottoman Turkey from Spain, was also banned during the “Citizen Speak Turkish” Campaign of 1930’s. Ladino is now a severely endangered language in Turkey, according to the UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger.

In his 2005 article “The Jews in Modern Turkey,” scholar Franklin Hugh Adler describes the anti-Semitic tendencies of Turkey since the early years of the republic: “Already during the 1930s it had become clear that a distinctive form of anti-Semitism, not simply disdain of Turkey’s minorities, had taken root. Cevat Rifat Altilhan, who published the first Turkish editions of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion and Hitler’s Mein Kampf, traveled to Germany where he met with Nazi leaders who subsidized his dissemination of German anti-Semitic propaganda. Between 1940 and 1998, Mein Kampf was published in twenty-nine separate editions, while the Protocols was published ninety-three times between 1934 and 1991.”

Members of Turkey’s Jewish community pray at Neve Shalom Synagogue in Istanbul on Oct. 11, 2004 (Photo: AP/Murad Sezer)

Anti-Semitic attacks in Turkey`s history include but are not limited to the 1934 anti-Jewish pogrom in eastern Thrace, the 1941-1942 conscription of the “twenty classes” (an attempt to conscript all male non-Muslim populations, including the elderly and mentally ill during World War II), and the 1942-1944 Wealth Tax that ripped non-Muslims of their financial power, as well as the deadly terror attacks against synagogues in Istanbul in 1986 and 2003.

When Yasef Yahya, a 39-year-old Jewish dentist from Turkey, was brutally murdered on Aug. 21, 2003 in his office in the Sisli district of Istanbul, many Jewish lawyers and doctors in Istanbul removed the signs on their offices in order not to have the same fate as Yahya.

The current Jewish population in Turkey is around 15,000. Many Jews born in Turkey left for Israel when the Jewish state was reestablished in 1948. And life is still not easy for those who stayed.

Yasef Yahya, 39, a Jewish dentist from Turkey was brutally murdered on Aug. 21, 2003, in the Sisli district of Istanbul.

“The Jewish community continues to live in a world of dhimmitude where subordinate status and second-class citizenship is uncontested,” wrote Professor Adler. “Turkish Jews, as many scholars have pointed out, prefer to remain ‘hidden’ and apolitical… Jewish children know they will never hold high public office, and are steered mostly toward commerce, engineering, or the physical sciences.”

The increasing pressures against the Jewish community in Turkey as well as the post-coup purges and the threats of the Islamic State (ISIS) seem to further escalate the Jewish emigration from the country.

For example, a 42-year-old Jewish businesswoman and mother from Istanbul named Betty recently told the Times of Israel: “Of course we’re thinking about emigrating. Everyone in the Jewish community is because it is hard to imagine a future for ourselves here. Many Muslims are, too.”

For in Turkey, not only Jewish citizens, but also their synagogues and cemeteries are targeted. The Jewish cemetery in the southern Turkish city of Hatay, for example, was attacked by “unknown assailants” in June. The wall of the cemetery was broken, the gate was torn down and the grave stones damaged. The cemetery includes the graves of Jews and Armenians, as well as of Muslims.

The archeologist Jozef Naseh, the former head of the Antioch Greek Orthodox Church Foundation, said in October that there are no Jews left in Hatay and that the remaining Christians in the city are threatened.

Apparently, anti-Semitism has dominated almost all aspects of life in Turkey, where Jews—like Armenians and Greeks—have lived since antiquity, long before the Turks themselves arrived from Central Asia. According to the 2015 Anti-Defamation League Global 100 Poll, 71 percent of the Turkish adult population harbors anti-Semitic attitudes.

But Turkey does not seem to care about whether Jews and other non-Muslim citizens will leave or stay.

Many Jews left earlier to go to Israel, not because they gave up on Turkey. And those who stayed in Turkey greatly contributed to the country’s economy and commerce.

But when even the last ones want to leave, it is a sure sign that they have no faith in the country’s future, its stability, equality under the law, or even their neighbors.

Source: Armenian Weekly

Link: Jews in Turkey: A History of Persecution