Three years ago, I worked at a polling station at a local election. A lady pulled up to our table in her wheelchair and wanted to vote. She went on at length to describe how, for years, she and her husband had come together to vote and had always gotten something to eat afterwards. After voting, she said that she would not go out to eat, since “food just did not taste the same” since her husband’s passing.

I worked at a polling station again this past June, in a local election. After an elderly man cast his ballot and I extended the “I Voted” sticker to him. He politely asked if he could have two, explaining that he always came to vote with his wife, but that his wife had passed away months before. He said that this time he had made the long walk to the polling place alone and wanted to take an extra sticker in her memory.

I thought I would start with this anecdotal introduction not because old couples are my favorite magic, but to show that voting is an integral part of American life—from high school class president to the leader of the free world.

This was my first” real” presidential election. In 2008, I was not 18 yet, nor was a citizen, but I watched with much joy as Barack Obama—the president of our generation—was elected. In 2012, I was a senior at Berkeley, and I sent in my ballot by mail. On election night, I cheered with friends and fellow students as Obama got reelected, though it did not come as a surprise to anyone. In a sense, it did not feel as if I was following a real contest.

This year I—as much as it was possible—abstained from political debates, as they seemed like a badly-staged circus.

On Nov. 8, I went to work at the polling station at 6 a.m.—to assist with the heavy task of conducting the democratic process. Voters came in, everything ran smoothly throughout the day, and then around 6 p.m., the first results started making their way to California from the East Coast.

At first, the states claimed were the ones that everyone thought he would claim anyway. But then the panic grew; this alarming feeling which I had felt once before.

On March 1, 2008, following the contested presidential elections in Armenia, the ruling elite felt threatened by the opposition and so the outgoing president ordered the security forces to violently disperse the opposition rally. After the darkest of nights, the center of the capital city lay in disarray with burnt cars and broken windows. In the middle of all, there were ten people dead in the hands of security forces.

Far away from Armenia, I sat on the floor of my bedroom and felt the complete onslaught of helplessness, knowing that the future of a place I cherished and the tomorrow of my peers who were in Armenia was being stepped on. I was completely incapable of doing anything. I wept because I loathed that feeling of personal minuteness.

On Nov. 8, I had that same feeling—as if somewhere else, certain people decided the future of America and the political reality of my generation, and that all I could do was to stare at a map and feel my heart sink in deeper as it turned redder.

I did not really know whether I wanted to scream somewhere or cry a little, but no thoughts came to my head, no words formed around my tongue, and no tears wet my eyes.

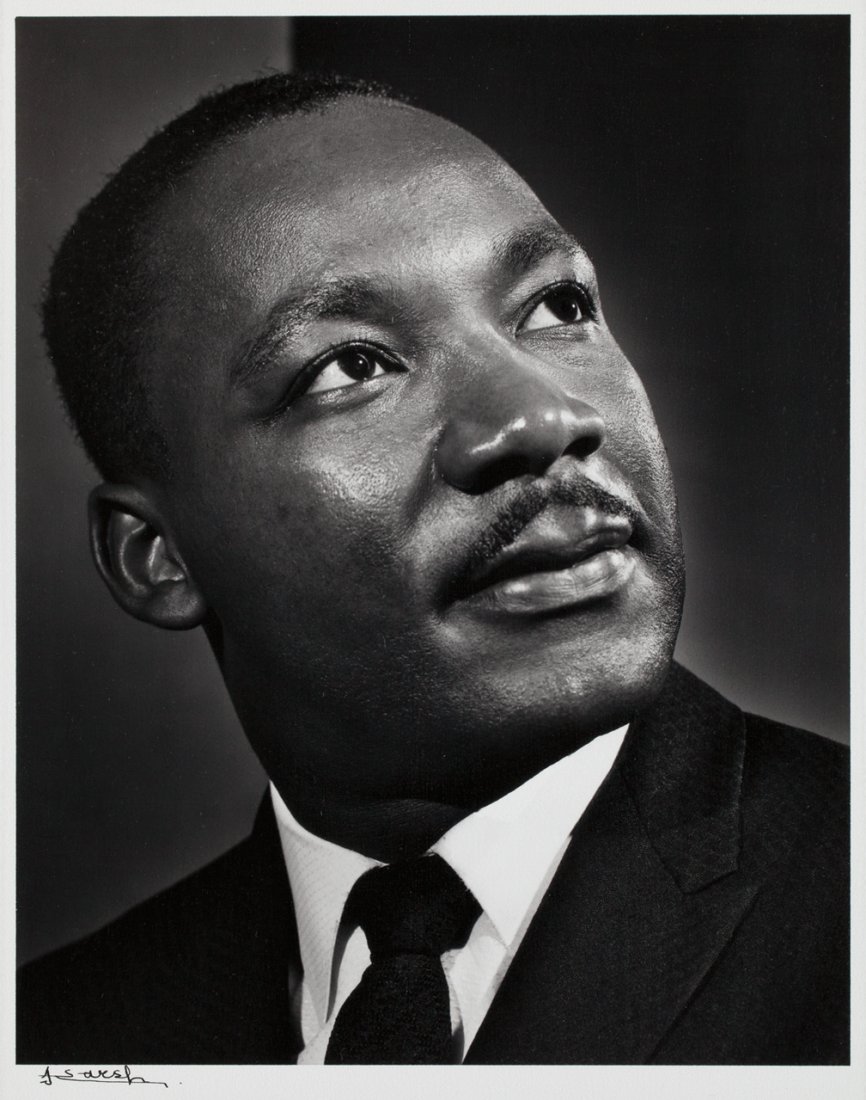

The following morning, the silence on my way to work was overbearing, so I listened to Martin Luther King Jr.’s last speech given in Memphis a day before his assassination. During his address, he spoke of all of society’s illnesses. But still in the middle of all that doom and gloom, he believed in America because he had “been to the mountaintop” and he had “seen the Promised Land.”

While this great man’s rich voice poured through my speakers and filled my car, tears rolled down my face. Not because the country that had birthed Dr. King had just elected what I consider to be a bigot as its president, but because we were so far from the mountaintop; that a certain layer of society had made its decision, which felt like it had carried the potential to roll us collectively further down the hill.

Maybe this year’s election campaigns played on the emotions of certain pockets of the society, who felt that the changes happening around them were too much. Maybe all these deep divisions lay dormant for decades since Dr. King had made his famous speech and now this man gave voice to those divisions. Maybe the fact is that half of the electorate is actually racist and sexist and could not bear to see the change in the white, patriarchal status-quo.

One thing that I know and can attest to is that the America that I have gotten to know in this past decade was already great. Sure, it was full of many cracks and tremors, but it was still great and I had come to accept that it was also a little bit mine. On Nov. 8, sixty million people decided that America was not great and that it was time to take it back from everyone else who also thought that it had become a little bit theirs.

I have struggled to grapple with what took place that day and if I told you that I understand what happened, I would be lying.

I cannot claim that I have been to the mountaintop nor have I ever seen the “Promised Land.” All I wish and pray for is that in this moment of internal and external confusion we all could be granted a tiny fraction of the vision of that great man, who even while walking through hell, had never stopped scaling that mountain or laying his eyes on the “Promised Land.”

Source: Armenian Weekly

Link: Far from the Mountaintop