By Gerson H. Smoger

Special for the Armenian Weekly

A musical taking place during the Armenian Genocide? Who would write that? Can it possibly be entertaining enough that non-Armenian audiences would want to see it? Impossible. And why would two people, neither of whom are Armenian, devote years to writing the story and literally hundreds of pages of music for such an improbable musical?

These are the questions my partner Jeffrey Sorkin and I have been asked.

And my answers have always been the same. As a life-long human rights advocate, why wouldn’t I devote myself to a story which takes place during the world’s first horrendous, unimaginable large-scale genocide? And once undertaking such a goal, why wouldn’t I hope to make it so entertaining that those who were as ignorant as I was about the genocide would not even realize that they were learning the secreted horrors of what happened?

Was I ignorant? Absolutely. I was in my twenties. I had a law degree. I had a Ph.D., and I professed to being a human rights advocate. Yet, I knew nothing about the events that resulted in the deaths of a million and a half people. Nothing.

So was my education about the horrors of the genocide a product of coincidence or fate? I had just graduated law school and I was working on a grant from the Ford Foundation at the United Nations Human Rights Commission. In Geneva, I struck up a friendship, or it may it be better to say that I was mentored, by an Armenian man named Set Momjian. Set explained to me how my historical education had been intentionally deprived as a result of a concerted effort to re-write history. Intelligent, well-read, believing myself to be worldly, I was nevertheless a victim. Set explained the details of the Armenian Genocide, which shockingly had never appeared in the extensive studies and history that I thought I had immersed myself in. He then enlisted my aid in lobbying for the recognition of the genocide at the United Nations.

Soon Set had to leave and go back to the States. So, was it coincidence or fate that Set and I discovered we lived within walking distance of each other in the suburbs of Philadelphia? Set was even kind enough to take my laundry back home to my parents. And when I returned to the States, he continued my education.

It was then that I started to sketch out an idea for the musical, which has become Some People Hear Thunder. In it, the protagonist would be someone like myself at the time, an itinerant young American traveling in areas where human rights were far from reality. As I worked more on the play, I decided to base that character on Herbert Bayard Swope, a young New York reporter who was sent by his editor to Germany. I would send him to Southern Turkey and that would be the play’s impetus, allowing the entertainment of New York to be mixed with the travails of those in Turkey. For an inspirational story during the genocide, Set pointed me to the story of those residing near Musa Ler. I read the recollections of those who survived, recorded in Cairo.

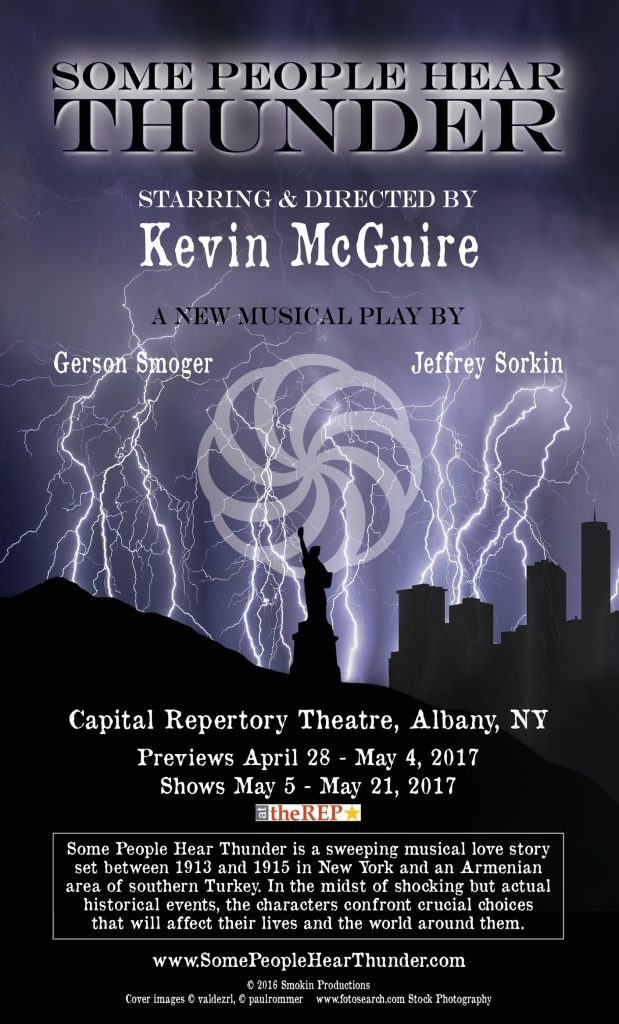

But the years passed. It was not until 2008 that the musical was finally for the most part finished. And it was not until the early spring of 2015 that Kevin McGuire, a veteran director and Broadway performer, told us that he thought it was so good that we had to plan an advanced workshop of the musical. Off we were to do just that in San Francisco. We decided to completely cast the play with an orchestra, although, as is customary in workshops, there were no costumes or sets. What we did not know, what we had no clue of, was that there would be a reunion of the descendants of Musa Ler that very same weekend in the Bay Area. What was the likelihood of that? We were then fortunate enough to have many of these descendants come to our workshop and watch the play. Was choosing this weekend out of all possible weekends coincidence or fate?

After the workshop, we went about deciding where to have our first full production. Because of Kevin’s long-term association with New York’s Albany Capital region, we decided that would be where Some People Hear Thunder would first be fully realized. Kevin, after all, had performed multiple times at the Capital Repertory Theatre and he had been the artistic director of nearby Hubbard Hall.

Our plans were made. The dates were set almost two years in advance. Everyone was hired. Then out of the blue I received an email from a 19-year-old university student, Meg Serian. She told me that she had been searching the Internet for information about her Great Grandfather, the Reverend Haroutune Nokhoudian, and soon found that he was a character in our play. Indeed, there are only three Armenians who lived at the time and who are depicted in the play. These are Dikran Andreasian, whose recollections were recorded in Cairo, Movses der Kaloustian, who returned to the new country of Syria after the war, and her Great Grandfather Rev. Nokhoudian. Until that call, I did not know precisely what had happened to Rev. Nokhoudian after World War I.

The reason I did not know? He had migrated to the United States and on Ellis Island his name had been changed to Harry Serian. I have now talked to several family members. It seems that Reverend (Badveli) Nokhoudian, who in 1915 was a pastor in Bitias, one of the villages near Musa Ler, had firmly believed that it would be impossible to resist and hoped that the severity of the Turkish punishment might be lessened by not initiating armed resistance. A deeply religious man, he led about 60 families who chose not to risk armed resistance. Tragically, most later perished in the “death march.” But Badveli Nokhoudian, as recounted in the autobiography that we have placed on the SomePeopleHearThunder.com website, managed to survive.

In fact, after surviving the genocide and travelling throughout the Middle East in search of a safe haven, Badveli Nokhoudian, his wife Siranoush and their four children eventually emigrated to the United States. There they finally settled in Troy, N.Y., a town just minutes’ drive from Albany where our play was already set to be performed. Coincidence or fate?

And how did he get to Albany? His boyhood friend from the “old country,” Jack Akullian, owned a group of markets, named Grand Cash Markets. Jack told Harry Serian that if Badveli Serian came to the Albany area, he would make sure that his three sons had work. Years later, in 1981, the Grand Cash Market in Albany was converted to become the Capital Repertory Theater– the same Capital Repertory Theatre where Some People Hear Thunder will be performed between April 28 and May 21.

Another coincidence…or fate?

For more information on Some People Hear Thunder, visit www.somepeoplehearthunder.com

Source: Armenian Weekly

Link: Some People Hear Thunder: A Musical of Coincidence or Fate