Growing up in a private Armenian school, I read a copious amount of Armenian poems. These poems, all part of the Armenian literary canon, addressed overlapping themes: identity, assimilation, nationalism, language, religion. From these poems, I learned how to be a correct Armenian–I must love my homeland above all else. I must resist any attempts to assimilate into American culture. I must worship Jesus Christ. And, above all, I must speak only in the Armenian language.

My thoughts, ideas, and even words were dictated to me by this literature.I clearly was not free to craft my own identity. After all, as the child of immigrants living within a marginalized community, there was too much at stake. My choices carried with them the seeds of my culture’s survival or ultimate death.

… as the child of immigrants living within a marginalized community, there was too much at stake. My choices carried with them the seeds of my culture’s survival or ultimate death.

I could not so easily conform to this formula regarding how I must live my life. So, after eighth grade, I decided to leave my Armenian school and transfer to a private, Catholic, all-girls high school (the clear choice for anyone seeking personal freedom). I chose this school because of the sense of community I felt among the students, and hoped I would feel empowered by the love and acceptance I received there to fearlessly undertake the task of re-imagining who I could be.

The school was noticeably white, and from the first day, I was determined to blend in. I began pronouncing my last name as “Uh-vee-dee-yan,” abandoning the traditional Armenian pronunciation, “Ah-vehd-yan.” When my parents called, I cupped my hand over the microphone as I whispered to them in Armenian. I skipped Armenian festivals and performances in exchange for Fourth of July barbeques and bonfires on the beach. I spoke little of my experience at Armenian school, pretending I understood my friends’ casual relationships with their parents, annual family reunions, and undefined curfews.

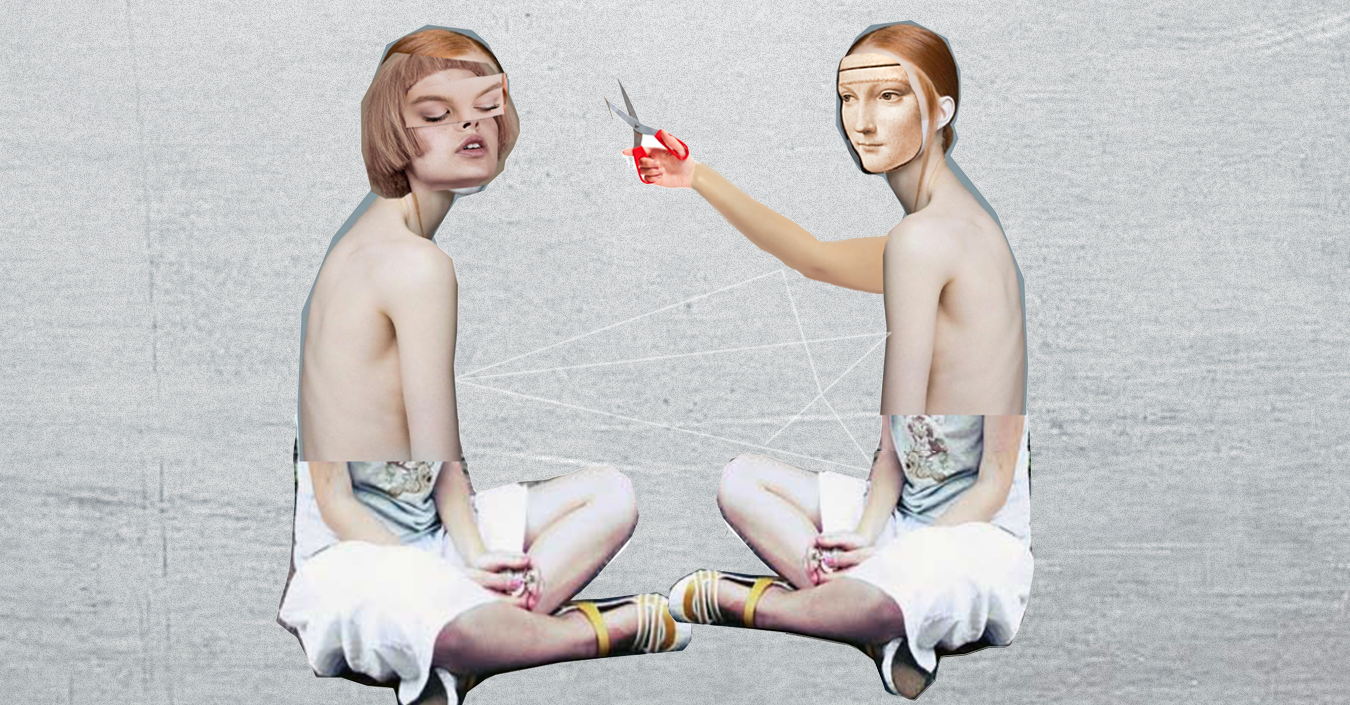

I believed that by chipping away at the parts of my identity that had controlled me in the past, I could liberate myself to explore those parts that had been previously suppressed: my sexuality, my femininity (or lack thereof), my potential atheism, my leftist political leanings.

By cutting away at the constraints that forced my body to take on a specific shape, I felt I could become the master over my body, designing myself based on identities that I, for once, chose. In this new paradigm, I could erase my darker skin tone, my hooked nose, my bushy eyebrows, transforming myself into a blank canvas which only I could paint. I would enjoy the freedom of the white American to sculpt myself into being, unbound by burdens or obligations inherited by birth.

Inevitably, this approach proved unsatisfactory. I fell into the same pattern of conformity; this time, to different ideologies: Catholic morality, strict religiosity, the gender binary, and, of course, the dominance of whiteness. Even if I wanted to proudly assert my Armenian heritage, there was no place in this community of proud white people for my Armenian-ness. (Except in one instance, in which I was asked to model for my high school’s pamphlet cover photo shoots to craft an image of diversity.)

My darker skin color and “ethnic” features cast me in the role of the outsider from the start. I performed the part every time I crossed my hands over my chest during communion under the gaze of the entire school (a required gesture for every non-Catholic during mass). While my attempts at assimilation were partially undertaken by choice, they were also necessitated by my high school’s overwhelming whiteness, and the obvious unwillingness to address this lack of diversity.

I eventually admitted to myself that to escape from my Armenian heritage would be impossible. Yet I still did not know how to construct a relationship with that identity. I had jumped between two ends of the spectrum—wholehearted immersion into the Armenian community, and complete detachment from it—and felt dissatisfied with both.

With my white friends, I felt too Armenian, yet when surrounded by Armenians, I was not Armenian enough. I was not anchored into any of the communities I floated through, and frankly, felt lost.

I had jumped between two ends of the spectrum—wholehearted immersion into the Armenian community, and complete detachment from it—and felt dissatisfied with both.

Fast forward two years. I’m sitting in an Armenian language class at the University of California-Berkeley, where I am now a student, reading aloud a poem I wrote about a woman who resists external policing of her body and mind. It’s a simple poem, amateurish in style, yet this moment is revolutionary. It’s the first time in my life that I see my Armenian heritage as compatible with my ideas on gender.

My feminist beliefs, which had been stifled in the past, seeming to exist in stark opposition of my Armenian culture, were here flowing forth in Armenian language. This poem differs vastly from the nationalist literature we consumed as middle school students. Yet, it is still, somehow an Armenian poem; just one that uniquely reflects my own ideology and creativity and worldview. Language has shifted from being a barrier that confines my speech and thinking to a closely-held tool that works on my behalf, shifting and warping to represent me and my thoughts. Through art, I recognized that the parts of my identity that had tortured me most became natural and intimate and flexible when I finally came to take ownership of them.

Writing Armenian feminist poetry unlocked an entire universe for me. I could take pride in my culture, my feminism, and my love for literature all at once. More importantly, I could define my own individual relationship with each of my identities, without compromising the other or feeling bound to an external prescription on how to organize my thoughts and beliefs.

There is no one correct way to be an Armenian. I am an Armenian Studies major, and I am an atheist, and I am the co-founder of a feminist theater company, and I am a progressive, and I am a poet who writes in Armenian. With that powerful “and,” I am following the model set forth in “Ծնունդ” and reclaiming my identities as my own.

|

Ծնունդ

Մէկ օր, ամէն կին հասկանում է

Որ իր մարմինը իրեն չի պատկանում:

Իր մազերը, անծանօթ-

Իր շորերը, օտար-

Իր ժպիտը, տարօրինակ-

Ինչպէ՞ս հասաւ այստեղ, որ իր էութիւնը իրեն զզուելի է:

Քո հայելիիդ առաջ կանգնիր, սիրելի,

եւ մկրատդ բռնիր քո ձեռքիդ մէջ:

Առաջ, մազերը, անծանօթ-

Երկար, գեղեցիկ, սարգուած մազերդ հաւագիր,

եւ կտրիր:

Յետոյ, շորերը, օտար-

Սուղ, համեստ, կանացի շորերդ

կտրիր քո մարմնի վրայից:

Վերջապէս, ժպիտը, տարօրինակ-

Մկրատով բերանիդ կողքերը կտրիր

ժպիտը, քաղցր, գրաւչական, սիրուն

թող ընգնի երեսիցդ գետնի վրայ:

Բայց դեր անհանգիստ ես զգում, ա՞յո, անծանօթ քո մորթի մէջ:

Մկրատը վերցրուր, համով,

եւ մորթդ քանդիր քո մարմնից

որ պատեանի մը նման բացուի:

Քիթը, աչքերը, արմունկները, ծունգերը,

Մատերը, ձեռքերը, ոտքերը, թուշերը,

Սիրտը, խելքը, ուղեղը, խիղճը,

կտրի՛ր, կտրի՛ր,

եւ ազատուի՛ր:

Վերջապէս, կ‘երեւաս,

կամ ուժեղ, կամ թոյլ,

կամ մազոտ, կամ անմազ,

կամ երկար շորով, կամ կարճ փէշով,

կամ զարդարուած, կամ պարզ:

Եւ այսպէս, առաջի անգամը քո կեանքում

դու քո հետ կը ծանօթանաս:

Բարի գալուստ:

|

Tsnund

One day every woman understands |

Editor’s Note: This past semester, the author of this op-ed published a poem in the Troika, UC Berkeley’s Russian, Eastern European, and Eurasian magazine, titled “Ծնունդ,” or “Birth.” The poem follows the journey of a woman who tears down the layers of her body in search of her authentic self, defying society’s control over her body. The author feels the poem is unique within the plethora of modern feminist poems in that it is written in Armenian, her mother tongue.

Author information

The post My Life as an Armenian Feminist (My Armenian Rebirth) appeared first on The Armenian Weekly.

Source: Armenian Weekly

Link: My Life as an Armenian Feminist (My Armenian Rebirth)