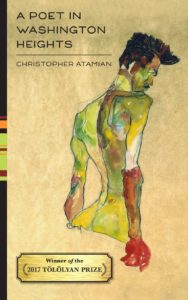

Winner of the 2017 Tölölyan Prize and with Egon Schiele’s arrestingly evocative “Man Nude in Profile Facing Right” adorning its cover, Christopher Atamian’s A Poet in Washington Heights is, at its core, a New York story. A deft essayist and critic, Atamian’s early poems cast him as a cultural anthropologist and an industrious craftsman of verse. Nancy Agabian so poignantly says his work cuts “to the core of queer desire (think redux of Allen Ginsberg’s “Please Master” riffs in Atamian’s “Seven” and, less so, “Red Pubes,” throughout, etc.). I exited the reading experience considering the extent to which place informs our identity. The blistering pageantry of Atamian’s poetry strolling in and out of memory might be viewed as a love song to the city that helped shape him and so many others because of its embrace of otherness and multiplicity and how we can be all ourselves at once.

Like Sondheim’s musical of the same name, Atamian’s “Into the Woods” starts off the book with a desire to explore that which we love and hold dear ona new and magical journey. For Atamian, it’s the Riverside Drive (the “Woods” hints at the “Park”) of his youth remembered, the terrain of his early days, where he imagines “great armies doing battle” next to “young lovers kissing” and how these “prattle / A history of my world.” Other poems throughout the journey toward and into Washington Heights embrace this idea of the world around us as a fairy tale we must walk through (at other times endure). There are the protagonist’s friends and lovers, long distance and/or held near/dear, and there are antagonists too who drive the story: perpetrators of crimes against humanity, inept leaders, a father who never understood, etc. As the book unfolds, the narrative moves more north toward and into Washington Heights, as the title affirms, and somehow the transition is a kind of awakening or new understanding in the writer as he recalls and creates. Atamian straddles the dreamy meaning-making of the child with the reposed and carefully sketched symmetry of the scholar.

Perhaps this binary and others like it are what create the tensions that drive us through the work. His exploration of what it means to be Armenian or “Armenian-ness” is one that stands out for me and one I will return to later in this essay. So often, we Armenians have viewed ourselves through the context of the Armenian Genocide, its lack of recognition, and our victimization. Atamian proposes, for instance, in “Armenians” that “we are survivors” and follows with the parenthetical question that resounds: “(That is true, but who is not?).” This is more of a compassionate gesture than a dismissive one, I think, especially in light of “I Refuse to Speak Armenian,” where the poet resolves, after much refutation of prodding, to

finally speak his native language, sentimentally, to his “medz mayrig.” This symbolic gesture, again, asserts the constant coalescence of the “past and present mixing”—an apt and resonant description that happens in the cup and saucer of our reading in “Strong Coffee.” These binaries feel more true in the context of a city that is known for its incredible highs and its devastating lows, of course. As Whitman once wrote, “we contain multitudes.”

Atamian is also a terrific friend, it seems, as epigraphs and odes pepper the work and the entire catalog can be seen as a series of tiny studies a painter might make in conversation with what or whom he has studied and the contemporaries around him. This is not an unusual takeaway as Atamian has written about art and film extensively, curated several related events, etc. “Holy” is essentially a response to Patti Smith’s “Spell.” Gregory Djanikian’s “Immigrant Picnic” is alive and well in “Hana Spills the Milk.” Basho breathes in his haiku. Ginsberg, I’ve already mentioned. Who else? There is even a study of French Surrealism in one of my favorite moments in “Margarita Locatelli,” who was the poet’s Italian grandmother.

We realize there is great balance in Atamian’s renderings of contemporary figures of notable celebrity, literary giants, and heroes of his home, so to speak. They shine with equal luminescences, these stars, and we’re prompted to think of our own becomings similarly. What informs who I am? What are the binaries inside me? The tensions? And how (and where?) will they be reconciled?

What’s particularly special about Atamian’s writing is how it carries both a grave weight and a vibrant whimsy (especially in form—tight, sing-songy end rhymes occasionally and repeated musical phrasings, etc.) while honoring the tethers of identity that shape our modern lives. Perhaps this is a call for less polarization and more integration as “We Are All Connected” surmises. God knows we have too much of that in our world right now. Perhaps Atamian’s mission was to integrate parts of himself through this exploration of the city that shaped him and the memories therein and, in doing so, prompt us to do the same. I can’t help but focus again on the aforementioned motif throughout the works, how we as Armenians should not be contained to what the Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie articulated as “the dangers of the single story.” We are not just victims of genocide, but we are survivors. We are both people who remember and people who forget as well. We are straight and gay and everything in between, notwithstanding the more conservative leanings of our respective tribes. We are scholars, yes, but forever children, too…moving toward greater understandings.

Author information

The post The Child and the Scholar: Christopher Atamian’s A Poet in Washington Heights appeared first on The Armenian Weekly.

Source: Armenian Weekly

Link: The Child and the Scholar: Christopher Atamian’s A Poet in Washington Heights