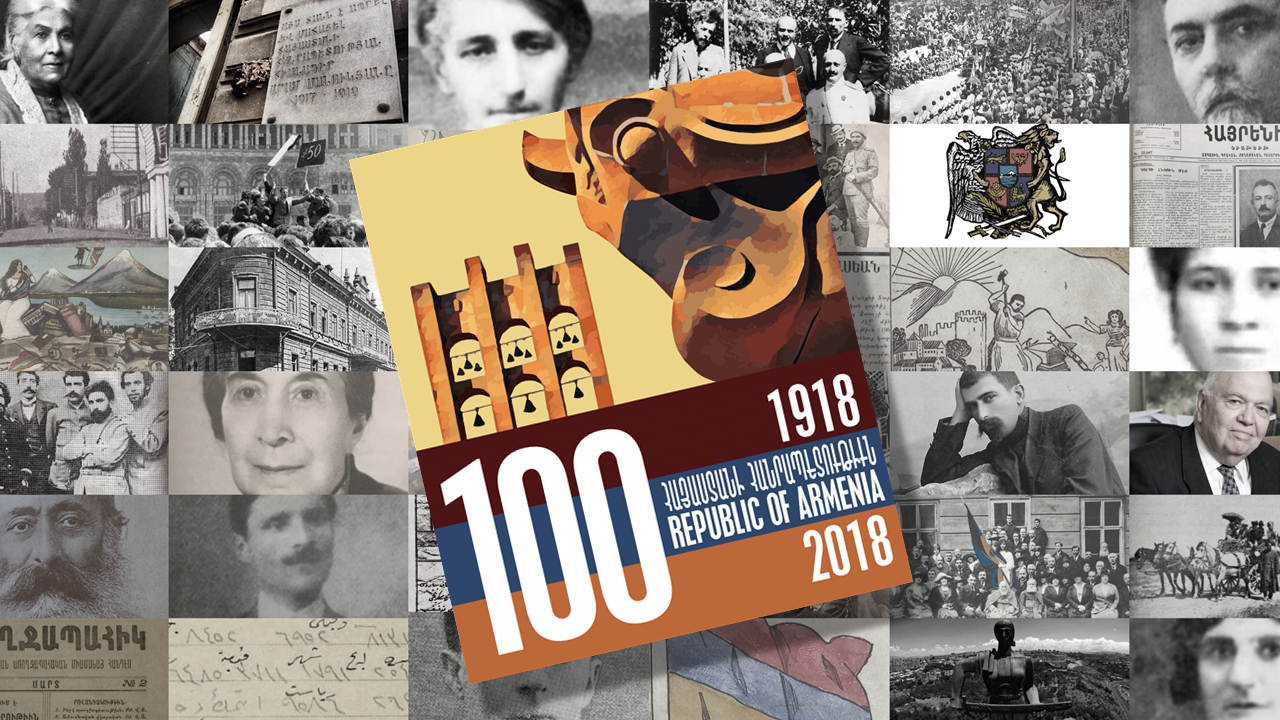

From the Armenian Weekly 2018 Magazine Dedicated to the Centennial of the First Republic of Armenia

A century after the establishment of the Armenian Republic, Armenia is once again at an exciting and fateful juncture. Over the last several weeks, hundreds of thousands of young, politically engaged citizens have poured into the streets demanding a better future. The countless acts of mass civil disobedience, which took place in late April and early May of this year, are telling examples of how the Armenian people—led by the youth—have rejected the political, economic, social, and cultural status quo of their current reality.

When thinking about the establishment of the First Republic as a turning point in modern Armenian history and its connections with the most recent developments in Armenia, there is one important theme that begins with 1918 and re-emerges vociferously in 2018, with critical outbursts in between.

The establishment of the First Armenian Republic amid the Great War and the Russian Civil War created a new political conjuncture in the Caucasus. After more than a century of Russian Imperial rule, the Georgians, the Caucasian Tatars (later called Azerbaijanis), and the Armenians were establishing their independent republics. As much as the collapse of the Transcaucasian Federation and the emergence of nation-states bear significance to these three Caucasian populations, Armenians understood it as the resuscitation of their long-gone statehood, the last vestiges of which were destroyed in Cilicia in 1375.

After being subjects and citizens of various empires for centuries, the Armenians were now carving out their own republic amid the chaos of the war—an act that seemed to defy their political trajectory of the previous 500 years. Most of the articles in this issue revolve around this central theme.

The establishment of the many institutions and relief efforts of the First Republic were made against all odds. A firsthand look into these grave circumstances and how the government of the Republic functioned can be glimpsed through George Aghjayan’s piece, which examines never-before-published documents housed in the Armenian Historical Archives in Massachusetts, while Hayk Demoyan’s article explores how, despite those harsh conditions, the people in Armenia celebrated the first and second anniversaries of their republic.

Anna Aleksanyan’s exploration of the venereal diseases among the Armenians in the First Republic, and the various ways Armenian doctors challenged the cultural and social stigmas and prejudices associated with them is another small example of the larger thread. Questioning the status quo through medical, cultural, or historiographical innovations is what many of the topics featured in this commemorative issue have in common. Lerna Ekmekcioglu’s discussion of Istanbulite Zaruhi Bahri’s thoughts on the First Republic not only sheds light on a voice emerging from a community that had just experienced genocide but also writes this prominent Armenian thinker back into history. Accordingly, Ekmekcioglu’s own work can also be viewed as an attempt to defy the gender-biased (i.e., male-dominated) nature of Armenian historiography.

The legacy of the Armenian Republic and the 50th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide propelled thousands into the street in Yerevan in 1965—an unprecedented challenge to the cultural and political hegemony of the Soviet authorities. As Vahram Ter-Matevosyan’s piece shows, the legacy of the First Republic made a lasting impact on the generation of the 1960s, who relied on the symbolism of 1918 in its attempt to voice political and cultural demands vis-à-vis the Soviet center.

The life and extraordinary times of one of the central figures of the First Republic, Aram Manoukian, are presented by Khatchig Mouradian , who provides a behind-the-scenes look into a revolutionary statesman-in-the-making and another example of a young Armenian who challenges current conditions and demands a new reality for his people through selfless acts.

The parallels between Armenia of the early 20th century and the present-day republic are undeniable, as can be seen in Jano Boghossian’s analysis of the little-known Second Congress of the Western Armenians. The history of the two-and-a-half years of the First Republic is not relevant merely for today; clearly, its demise had a profound impact on both the people of Armenia and Armenians around the world, as demonstrated in Michael Mensoian’s piece.

And, as Professor Richard G. Hovannisian notes in his exclusive interview, though the First Republic was unable to reach its coveted goal of a “Free, Independent, and United Armenia,” and though it had shortcomings, “the Republic had put Armenia on the map.”

The short-lived First Republic occupies a significant place in the storied history of the Armenian nation. Today, a century later, what is most important is to draw worthwhile lessons that apply to our current statehood, to understand the crucial role the First Republic played in developing Armenian sovereignty, and to grasp that real renewal can take place only by pushing boundaries—by challenging the status quo.

Author information

The post Armenia a Century on: Lessons in Challenging the Status Quo appeared first on The Armenian Weekly.

Source: Armenian Weekly

Link: Armenia a Century on: Lessons in Challenging the Status Quo