Some Armenians, Fed Up with Injustice, Leave the Country. Others, like Shahnazaryan, Stay and Resist…

Part Two of David Barsamian’s Interview with Anna Shahnazaryan

Mountainous and landlocked Armenia has had a long history, but as a nation state it is relatively new. Armenia declared its independence in 1991. This wide-ranging and revealing interview with Anna Shahnazaryan, an environmental activist and a feminist based in Yerevan, covers many issues facing Armenia.

Left with a legacy of 70 years of Soviet rule, Armenia has a major corruption problem. The adoption of neoliberalism by elites has produced massive inequality. Oligarchs dominate the state and the economy. Unregulated mining is causing environmental damage. Water supplies are being threatened. Quality healthcare, extremely expensive, is available for the rich. Education? More of the same. The media parrot the government line. Patriarchy and misogyny persist. Women are seen as child-producers for the defense of the nation. A decades-old conflict continues with neighboring Azerbaijan. Both that border and the one with Turkey are closed. Some Armenians, fed up with injustice, leave the country. Others, like Shahnazaryan stay and resist.

This interview, which was recorded in Yerevan, on June 9, first aired on Barsamian’s Alternative Radio (AR) program and was transcribed for the Armenian Weekly (read part one here).

To listen to the original recording, visit https://www.alternativeradio.org/collections/newly-digitized/products/shah001.

Help AR spread its progressive message to larger audiences at a time when it’s particularly needed. AR has no underwriters, government grants, or advertising income. Radio stations receive AR programming free of charge and the program solely depends on its listeners to sustain AR.

AR welcomes tax-deductible contributions for any amount. Checks can be mailed to RISE UP-Alternative Radio, PO Box 551, Boulder, Colo. 80306. AR could be contacted at 800-444-1977, Monday–Thursday, 8:30 a.m.–4:30 p.m., Mountain Time.

***

David Barsamian: And what about the important area of education, the future of the country? Is quality education available and affordable?

Anna Shahnazaryan: Not really. It’s underfunded. Also, the education system is used as a pipeline for ideology. Ideology is another thing that I want to touch upon. What kind of ideology? It’s corrupt. Those who promote this ideology, seed nationalism in children, seed loyalty, obedience, and servility—these are the values that are beneficial for the elite, both political and economic (or maybe they’re actually just the same) and colonizing forces. No doubt, we have multiple colonizers, both internal and external.

Russia has military bases here, and owns much of Armenia’s mineral resources, but there is also the influence and role of international capital. Global corporations and financial institutions are also forms of neocolonialism. The educational system is planting these seeds in children growing up with no critical approach. They have mechanical skills or knowledge. They grow up highly militarized, with a lot of hatred. And this hatred is perpetrating not just war but also a social fabric that is distrustful, because they have grown up in an ideology of not just external enemies but also internal ones.

The ideology of nationalism breeds fear of internal enemies. Anybody could be an internal enemy. A feminist is an internal enemy in this country. In particular, some newspapers will actually call out feminists or human rights defenders or even queer people and defenders of LGBT rights as internal enemies. So children are growing up with a lot of these things that are not conducive, in the future, when they become adults, to building a cohesive society. We’re growing up in an atomized society.

This is paradoxical because we’re known to be more communal. We like having neighborhoods. For many centuries Armenia wasn’t independent, [it] has been a colony. We developed a sense of living in clans. But clans sometimes also had a positive aspect, allowing survival of mutual support through family ties, through communities, through neighborhoods. So the communal lifestyle is going down not because of this widespread liberal individualism but very bad values of distrust, of hate, of not trusting grassroots independent mobilizations, because then they would say, “You’re destroying the foundations of this country or the foundations of family.”

All these values are planted and bred in a school system that is underfunded. Many schools are being closed down. The elites send their children to private schools, which are extremely expensive. There is this glorification of private schools. People who are oligarchs abroad, in Armenia are considered as benevolent donors. They may live in Russia or in the U.S. or Europe. They are seen as successful businessmen who are doing charitable work in Armenia. And they consider building an expensive private school a charitable activity? That’s very strange. This is how the educational system is degraded.

Quite a few villages, which have largely been depopulated but still have, say, 10 kids, [and] these kids don’t have a school. The nearest school is in the village next to theirs, which can be 10 kilometers away. There is no inter-village transportation. How are these kids going to get their education? These are the kinds of social problems that we are facing at the moment. Right now, the new minister of education is again talking about another school optimization, which means we cannot sustain a school or a facility for just 10 children in the villages. We have to optimize the system. Which is, of course, another manifestation of austerity.

“Austerity” is a term that is not used in Armenia. We’re trying to bring it to the fore. This is a global phenomenon taking place. Armenia is part of global processes, and we should start using these neoliberal terms. The manifestation of the process is something that people know, because they feel it on their skins.

Many university students, also, don’t find quality education here, [and they] seek education abroad. The existing—what they would consider foreign—higher educational institutions, let’s say the American University of Armenia, are part of the establishment and not an independent academic platform where critical thought is developed. Go on their website, [that of the] American University of Armenia, which is a private university but accredited in the U.S. and in Armenia, it says, “We are very proud that our alumni, our graduate students work for the World Bank, for the government of Armenia, or for this or that ministry.” We know these are the institutions that promote neoliberalism.

D.B.: But you are well educated and a critical thinker. Didn’t you come through this system?

A.S.: I’ve rejected the system so much. I’ve been inside it and resisting it. I couldn’t attend my last years of school. I just hated it. It wasn’t providing me with motivation. I was accepted to the Linguistic University of Armenia in 2000 and I had a chance to study abroad with a U.S.-funded educational program for one year. In terms of just going to university, having discussions, reading textbooks, writing papers—I’m not talking about the content of this education—coming back home, you don’t have a system that is educational. It’s just the lecturer giving a lecture, we copy that, we take an exam, and just repeat the same thing by heart. That’s not education. So I was resisting that, too. I was not attending many classes. At least the good thing about the Linguistic University was that if you work along with your studies—and I worked as a translator already in my final years—I was privileged in that way, of skipping a lot of classes and just taking the exams. And then I had the opportunity to do a master’s program abroad. But it’s not that that built my critical approach.

I think different factors have been conducive to my being a critical thinker, such as my involvement in various social campaigns, my learning from peers, my involvement with international academic groups that are discussing social campaigns. So the factors that have driven me to become who I am, an active citizen and a critical thinker, are more the environment—what I did, who I did it with, what kind of news I was reading, what kind of outlets I was following, and how I was feeding my own knowledge and intellect.

D.B.: How do you make ends meet?

A.S.: I’m a freelance interpreter and translator. But that allows me to survive on the minimum possible and leaves me enough time for activism.

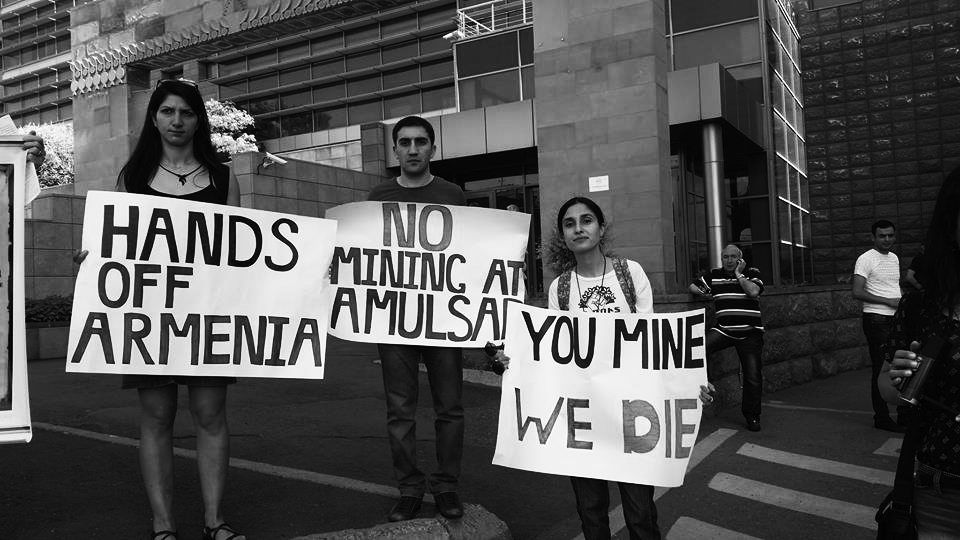

Right now, I’m working with a group on a campaign against Amulsar, a gold mine that is supported by both the governments of the U.S. and Britain. The embassies here have been promoting and supporting this project. Also, the IFC [International Finance Corporation] was the initial capital holder in Amulsar. It’s the disaster of disasters. Earlier, I was talking about water resources and Lake Sevan. If this mining operation takes place, it will threaten Lake Sevan. This is just unimaginable.

So I’m working hard on trying to halt Amulsar, which has its tail, or maybe feet, or whatever, rooted in British offshore tax havens, particularly the Channel Islands. This is where Lydian International, the mother company, is registered. We don’t know the exact owners of the mother company, but there are many signs it is affiliated with Armen Sargsyan, the current ambassador of Armenia to Britain. He is a businessman, not a diplomat. He has huge businesses, all the way from owning gas and mines in Kazakhstan and Uganda.

This is something that is not talked about in the Armenian press. There is not a single investigative Armenian-language piece on him. There are a few mentions of Armen Sargsyan not declaring, according to law, his property and his income. All public servants have to do that. He has not. He has been a public servant for a long time. He has also served as prime minister. And for many years he has been ambassador of Armenia to the U.K.

There are indirect linkages between the Amulsar mining project and him, for example, and other big businessmen who are considered philanthropists, such as Ruben Vardanyan, who is co-founder of the Aurora Prize. The bank he owns has given a pledge to finance part of this mining operation. People who are affiliated with AGBU, the Armenian General Benevolent Union, who are rich businessmen, also have shares in this company, or its subsidiaries.

Because, as I said, this company, even though its parent company, Lydian International, is registered in the Channel Islands, we don’t know the owners. But it has all sorts of subsidiaries. The shareholders of these subsidiaries are more or less known.

I’m working intensively on trying to stop Amulsar. But locally it would not be possible. A lot of pressure also has to come from the Armenian community abroad. Because it’s Armenian businessmen and Armenian institutions like AGBU that support this mining project. So anything that the Diaspora Armenians who will read this or hear this radio program can do about this will be a great help.

The Armenian Environmental Front, a grass-roots group, a civic initiative is coordinating a lot of these efforts. Their website is armecofront.net; I’m supporting this group and am involved in this campaign.

D.B.: The U.S. embassy in Yerevan is enormous. Why is there such a large embassy in a small country with a slight population?

A.S.: In the central part of the city there is an analogous building, not horizontal but vertical; that’s the Russian embassy. The U.S. embassy is fortified. We don’t even know what kind of departments operate there. There is a military attaché, but what else is exactly there… we don’t know much. And it’s not incidental that I mentioned the vertical analogous embassy, which is the embassy of Russia.

I think the reasons are more geopolitical and are not necessarily related to Armenia. But we don’t [really] know why these big embassies were built and what purpose they serve.

D.B.: A few years ago, WikiLeaks released classified documents from the U.S. embassy in Yerevan, which were a virtual Who’s Who of the oligarchs in Armenia: who owns what, what are the subsidiaries?

A.S.: I’m happy that some media have picked that up. These documents did not express a critical approach or a concern about the oligarchs and their holdings; it was just to lay out the facts and where U.S. business interests could be. So, understanding who owns what allows for what can be privatized further, what can be purchased further, maybe from an oligarch or maybe from the state.

One of the most horrible deals that was strongly supported by the U.S. embassy was the privatizing of one Armenia’s largest hydroelectric power stations, Vorotan Hydroelectric Cascade. It was sold to ContourGlobal. It is a company that is, again, registered offshore and doesn’t have a long history of existence. The scheme is just laughable, because the company doesn’t even have its own money, doesn’t even have its own loan. The way they purchased it means literally giving it away. The Armenian government always says, “Oh, we’re short of money, the budget is short, so we will sell this off and generate some revenues.” But this didn’t even result in revenues. This is going to be paid in installments. That is almost like giving it away.

Maybe [the U.S. embassy’s research] is documentation, not revelation of much of what we know or what we feel and sense. But from an embassy perspective of why they were actually doing it, it was just a list of who owns what and what kind of power they have. Political power, linked with economic power, is what sustains the ruling elite. But it’s also possible to shatter some of that, maybe get some other gains. It [that power] doesn’t have to be [held by] a local oligarch; it can be also possibly be [held by] a global oligarch. Why not?

D.B.: There seems to be a pattern—with the collapse of the Soviet Union in late 1991—that in the states that emerged, including Armenia, but also the other former SSRs (Soviet Socialist Republics), [a pattern] of corruption, concentration of power, media control, and oligarchy. Do you think that’s a direct result of the way the Soviet Union operated?

A.S.: What you just described is sometimes called transition countries. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, particularly the U.S. and the World Bank penetrated all these states with what they called transition support and aid, providing a lot of money for so-called reforms in these countries. These countries, of course, were reformed.

This is not even ambiguous. It is explicitly mentioned in the names of these programs. For example, there is even a law in the U.S. called the Freedom for Russia and Emerging Eurasian Democracies and Open Markets Support Act that provides financing for building open markets. So everything was done to create an open-market economy, or open-market state. Having an open-market system can create accumulation of power and inequality and serious environmental problems. This is what capitalism is actually creating.

So this rapid, what they call, transition, but what I call a transformation into a capitalist system, is combined with a Soviet legacy of totalitarian rule, of a police state, which has the power, has the weapons, and has the monopoly over violence to grab resources and to make money. These [two systems] were coupled.

What we see now in the oligarchic echelons is that many of them are people who held power in the Soviet era, who were mostly related to the police or the then KGB, now its successor, FSB, the Federal Security Service. For example, Serge Sarkisian, the current president, his background is in the FSB, and in the Soviet period it was the KGB. So he was a KGB servant. He also has huge economic power.

So what I want to say to your question is, yes, but it’s coupled with capitalism.

D.B.: Is Serge Sarkisian related to Ambassador Sargsyan in London?

A.S.: No. Their family names are just a coincidence. But, of course, nothing is taking place without mutual agreement. Ambassadors are normally appointed by the president.

D.B.: How would you describe the state of feminism in Armenia today?

A.S.: Luckily, it’s growing and expanding. This is something that I’m really happy about and supporting. I’m involved in feminist groups and initiatives. The capitalist system that exists all over the world is also either supported by patriarchy or it’s the chicken and the egg story; it’s either supported by patriarchy or supporting patriarchy itself.

D.B.: Do women have access to reproductive rights?

A.S.: We still have access to reproductive rights. But it’s not publicly funded. As I said, most of the healthcare system is privatized. Seeking family planning would be something that would have to be paid for.

Something related to the militarization of the country is that all birth-related services are provided for free. It was done to promote reproduction, because being in a state of war and with quite a bit of militarized rhetoric, women are viewed as producers of soldiers. A country at war needs a product—bodies. That’s a very sad situation that puts a large physical and moral burden on women to give birth to children who potentially will be soldiers, who may eventually fight and die.

Militarization contributes to violence against women. By that I mean both direct and structural violence. As I mentioned, a moral obligation is put on women to give birth and also not to complain when their sons are killed in combat or in noncombat situations. The army is a closed and violent institution, and there are killings among soldiers and between soldiers and their officers. There are also cases of suicide; a lot of humiliation takes place in the military.

Women are the ones who are called upon by officials to be mothers of the nation, to give birth, to be mothers only and not human beings and not women. This is even inscribed in, for example, the Republican Party’s ideology. In a written party document they say, “Women are first of all mothers and Armenians,” and then afterwards they are something else, teachers or whatever.

D.B.: The Republicans being the dominant political party here.

A.S.: Yes, and a very conservative party.

D.B.: What about access to abortion, given the view of women as child producers?

A.S.: They still have access. This is one of the positive legacies of the Soviet health system. Unfortunately, we have this huge issue of selective abortion. So there is nationalism and militarization and also—and it’s not just a recent thing, it has existed for centuries—preferring male children. At the moment, we have this crisis of girl fetuses being aborted because there’s a preference for giving birth to boys.

D.B.: In terms of divorce and owning property, are women given their rights?

A.S.: By law, yes. There will be people who would like to discuss things on the level of what, for example, CEDAW, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, prescribes and what the Armenian government is doing. So they would start discussing those things, and then the Armenian government’s position would be, “Oh, gender equality is ensured in this country at the level of laws; women don’t have any legal obstacles.”

But that’s not the kind of discourse I want to lead. Even though women have all the rights and there is no legal discrimination against women, there is also no legal or even social promotion of gender justice. I’m not using the word gender “equality.” I want to use gender “justice.” For example, women can own property. But what happens with a lot of these oligarchs is when they want to hide their identity or wealth, they use their women, their wives, as a cover.

According to the previous Armenian constitution—which was changed about a year ago and a new constitution was adopted—a public official is not allowed to be a businessman. They have to choose: either public service or business. So a lot of these public officials who are businessmen would use their wives’ names to register their businesses or their bank accounts. Which means, again, a very instrumental approach to women. Women are utilized to do this.

Or, for example, there have been cases when microcredit was provided to women only, to support women’s entrepreneurship. Women would get the loans, and then the husbands run the business.

So it’s always important when we’re discussing these issues to look at the micro level, on a case-by-case basis of what actually the liberty of women is in terms of doing their own entrepreneurship or being involved in decision-making, etc. And they’re not. They’re driven—especially now, very rapidly, because of militarization—into homes, into kitchens, and motherhood, because this is what the military elite wants of women. On a legal basis, they have rights. In reality, they don’t.

But in the legal system also there is this thing—for example, we talk about femicide. Women are being killed at home.

D.B.: You mean domestic violence.

A.S.: Yes, and in high numbers. What happens in the courts is that sometimes these criminals are acquitted or given light sentences, three or four years, for example, for murder. And the judges—most of them are male, some are female—would find extenuating factors, for example, “Oh, the husband was jealous.” So they would consider jealousy as a mitigating factor in the crime. This shows that there is a systemic discrimination against women.

Or, for example, domestic violence like beating, battering resulting in women suffering serious physical injuries and health problems, would be pardoned by the court. You know with what reason? The husband was in the military, has served the country, has fought in Karabagh and liberated it. So being a member of what they call the yerkrapah miutyun, the veterans’ union…can relieve you of responsibility for a crime. They can get off with a $100 or even $50 fine for extreme humiliation or battering for years.

In one of the worst cases, the husband was battering the wife, and the older daughter was also being abused. He would keep the older daughter in the barn chained from the neck next to the cows as punishment. This person got off with only a $50 fine.

D.B.: You’ve critically described some of Armenia’s salient problems. Could you suggest some solutions? If you could close your eyes for a moment and imagine a different Armenia, what would it look like?

A.S.: Before I could imagine a different Armenia, we would definitely need resistance. This is something that I embrace, a spirit and action of resistance. Because it is through resistance that we imagine alternatives.

Having been in various social campaigns—and this is a normal reaction… you start saying No. We say no to the mine in the forested area in Teghout, for example; we say no to the Amulsar mine, which will jeopardize the water resources of this country. But then we came to realize that we need alternative economies, we need alternative ways of activating community life, especially when the villages are so deprived. And so resistance builds imagination. And relying on this imagination, we then imagine what could be the future.

For the future, I imagine a place that is largely like a national park, a special protected area. And I think of Karabagh, a region where there is an ongoing war, where both Armenians and Azerbaijanis have fled and died, is a very contested place with a unique landscape and nature. It could be a completely protected area. Which means you can’t even fight there. You only think about preserving this place for current and future generations.

I imagine a place where we lead a sustainable livelihood. This word has been abused a lot, but when I use the word “sustainable,” I mean in its good sense—a livelihood that is in harmony with nature, with its resources, with the social fabric; that is also sustainable, that builds social cohesion and does not destroy it, and of course, people living in peace and happiness.

At the moment, when you walk in the streets of Armenia, you will see people with grim faces. They just walk with their heads down, gloomy and unhappy. What I want to see is free spirits, and smiling and happy faces.

Source: Armenian Weekly

Link: Armenia: The Struggle for Justice (Part II)