Special for the Armenian Weekly

In post-genocide or post-catastrophe periods, women are often left out of the national collectivity. That is, in the gendered classification between public and private space that characterizes national structures, women are restrained within the private space and their contributions to public life of the nation are often ignored or erased from history.

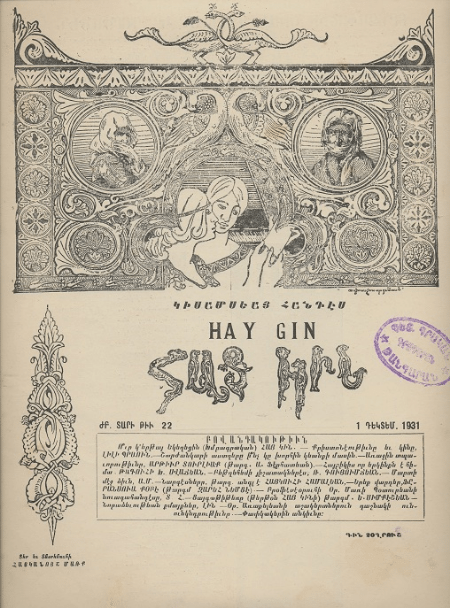

The cover page of a 1931 ‘Hay Gin’ issue. The woman in the center symbolizes the ‘New Armenian Woman’ while the two on each upper corner represents the old generation.

Nations are frequently conceived as masculinized entities. Lois A. West emphasized that in colonial struggles, women are perceived as the booty of the male conquerors. This is why often male oppressor uses sexual violence such as rape as a weapon of humiliation against the rival group. Rape in this context is seen as “violation of other group’s honor/ dignity” so that the victim remembers her “shameful” past and feels inferior towards the oppressive state/group. Anne McClintock further explains that national communities often rely on the male recognition of identity, that is national power is recognized as male power. The nation as such is formed through homo-social bonds and through exchanges of power between men. In imperial situations, women become the objects of exchange, evidenced in processes like the feminization and eroticization of the land and of the colonial subject. Consequently, they are constructed into symbols of the nation, themselves unrecognized as active participants. Although women have engaged in nationalist and anti-colonial struggles in many ways, there are consistently perceived as secondary to men, their efforts hidden or invalidated.

Coming to the Armenian context, it is important to show how Armenian feminists tried to reconstruct the collective identity, redefine the boundaries of this collectivity, and renegotiate the masculinized national identity inherited from imperialism even during the early phase of the post-genocide era.

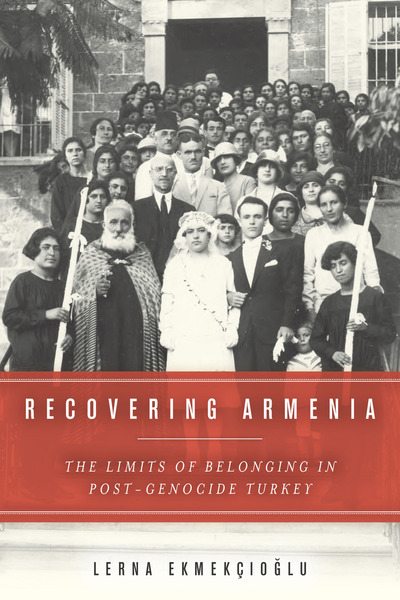

In her book Recovering Armenia: The Limits of Belonging in Post Genocide Turkey, Dr. Lerna Ekmekcioglu, explains how Armenian feminists—despite the clash with religious institutions, patriarchy, and nationalism—shaped the post-genocide collective identity and raised their concerns even during catastrophic period. During that period, Armenian feminists had two goals: the betterment of the condition of women and the betterment of the nation.

For Armenian feminists, mothers needed to be educated, so that they could raise a new generation with a new national consciousness. Thus, Armenian women had to be educated but “not transformed too fundamentally” because they, in their songs, food, crafts, stood as the nation’s uncontaminated unique core, which distinguished Armenians from other nations in the empire.

From the 1860’s a new Armenians female urban intelligentsia was formed and started to raise questions regarding the role of women not just in the Armenian society, but also throughout the Ottoman Empire. For the Turkish state, Armenian women were perceived as a threat. The Young Turks, in their final solution of the Armenian Question, not only persecuted the men but also sexually violated the dignity of the women through enslavement, forced Islamization, and rape, thus “humiliating a whole nation.” For the Turkish genocidal agenda, Armenian women were conceived as being devoid of the agency to organize political resistance, and because they could not reproduce Armenian children without their men (who were separated from them and murdered), they were better recycled than discarded.

As the war ended, Armenian feminists filled the gap of Armenian intelligentsia in Constantinople, who were murdered on the eve of April 24, 1915. Thus, with the effort of Armenian feminist activists, the Armenian Red Cross of Constantinople was founded to take care of the pregnant refugees and the sick. With the help of the Armenian Patriarchate and European humanitarian agencies, activists ran the shelters of the rescued Armenian women and orphans from Turkish or Kurdish homes.

For those feminists and the Armenian leadership, orphans represented the hopes of the Armenian nation because they personified a certain kind of revenge; Armenians associated living with vengeance. Existence—as an individual, as a community, as a nation—became more than just a state of being; it had turned into a act of political resistance. As Payladzu Captanian claimed, “We were sure that even if we managed to keep three children alive, we would have already taken our revenge on the enemy. There would be established three families on the ruins of one ruined family, and that’s how the Armenian Nation would come back to life and reconstitute itself. Then, it was not important that we would die. They had to live. We would survive in them”.

Hayganush Mark one of the leading voices of Armenian feminists stood at the forefront of the battle against “women’s enslavement” and took it upon herself, along with her comrades at her journal Hay Gin (Armenian Woman), to convince the Armenian nation that women’s emancipation would not distract from, but would ultimately add to its revival. Hay Gin’s first editorial, on Nov. 1, 1919, began by affirming that the First World War, despite its tragedy, had given birth to some “rare favors.” Hay Gin’s first editorial in entitled “Our Road” stated:

“During those four hellish years, we—especially Armenian women—have demonstrated that beyond, housework and child care we can bear with all sorts of hardships. We can also be trusted with jobs and markets; and we have proven to those who have spoken against our cause that it is best that they keep their mouths shut. If we consider what we have accomplished during the Great War, how we stepped in for our husbands, brothers, children, and what we also have achieved after the war, how we embraced our orphans, how we shed tears as they cried, and how we took our duties seriously, our fate is bound to change. We will assume our duties, create our rights, and shape our roles. Our feminist instincts will not hinder our homemaking chores. Rather, the rebirth of our sex will take us to the summit of our nation and to the summit of our fatherland.”

Armenian conservative circles based their argument on Rousseau’s claim that women’s meddling in men’s spheres (that is politics) would question the morality of their motherhood. The Armenian leadership raised the question how can a mother devote her time to politics while the orphans are desperate in need of care. Given the “Wilsonian principles,” which emphasized on demography of self determination rather than territory, the Armenian leadership began to arrange marriages between Armenian men and women, and retrieve young children and women kidnapped into Muslim houses. Their retrieval was meant to be an act of revival, restoration and revenge. Armenians retrieved what the Turks had stolen from them and employed the women and girls to reproduce Armenianess.

Given the pre-Genocide ideas about purity, Armenian leaders started rescuing the rape victims and turned them into “proper marriage candidates” and future mothers. Armenian newspapers encouraged Armenian men not to reject those women since they were “innocent victims who cannot be held morally responsible for their miserable condition.” For the conservatives, Armenian women had only humanitarian limits and should devote themselves to the raising of men for the nation rather than assuming public roles. Otherwise women would have committed a sin against their nation.

Armenian feminists responded to these claims saying feminism is not the enemy of the nation or of men. Feminism called for women to be in marriages conscientiously and for them to embrace their rights, not by force or unconscientiously. Therefore, men should understand and see their women as equal partners, with the same rights, same responsibilities and same dignity. Thus, the Armenian Women‘s Association started to organize and sponsor workshops to rehabilitate those “fallen women” so that they can be independent and able to earn an “honorable income” in the future.

Armenian feminists—taking into consideration the imperative demands of the chaotic situation in the post-genocide period—defended the Armenian cause by taking on their shoulders the “burden” of the orphans and refugees. It is not surprising that Armenians call their homeland “Mother Fatherland” (Mayr Hairenik), because it is through the motherhood of those activists that our identity was reshaped and the nation endured the agony of genocide and its consequences.

Source: Armenian Weekly

Link: Armenian Feminism and Reconstructing the Post-Genocide National Identity