Special for the Armenian Weekly

My grandfather Haroutiun Arabian was not destined to be one of the 1.5 million. Like many Armenians, he was born in an Armenian village in present-day Turkey. As best as he knew, he was born in the summer of 1907 in Muratça—one of 13 small Armenian-speaking villages in the province of Bilecik in the Ottoman Empire.

In the early 1800’s, the Sultan’s government had relocated these Armenians from the Yozgat and Kayseri provinces with the intention of breaking up the “Armenian majority demographic zones” and assimilating the “rebels” into the rest of the Ottoman Empire: the ultimate goal of this relocation was to Islamize the Armenian population. This was one method to deal with the Armenians. The other method was unfortunately yet to come.

Thankfully, they failed, and I am proof of their inability to conceal their crimes. I am one of Haroutiun’s Armenian granddaughters, living in the United States and sharing his story.

In the early months of 1915, Haroutiun’s father Garabed and all the adult male villagers were disarmed and then taken into the Ottoman army’s “amele-taburlari,” which was the unarmed unit of the labor battalion. The men in this working battalion were forced to work in the most severe weather conditions, at high altitudes, and without proper clothing, food, water, and sleep. Their main function was to build and repair roads and railroad tracks. Many died from exhaustion and disease.

Some escaped into the mountains, but most were eventually executed. My grandfather never saw his father or adult male relatives again; he had no one left to protect him. I won’t be giving away the rest of the story if I tell you that this was the beginning of the making of an incredible man with an amazing will to live. A will that still endures in me thousands of miles away from our ancestral home. The same will that survives in the millions of Armenians still marching, yet creating new lives and new homes all over the world.

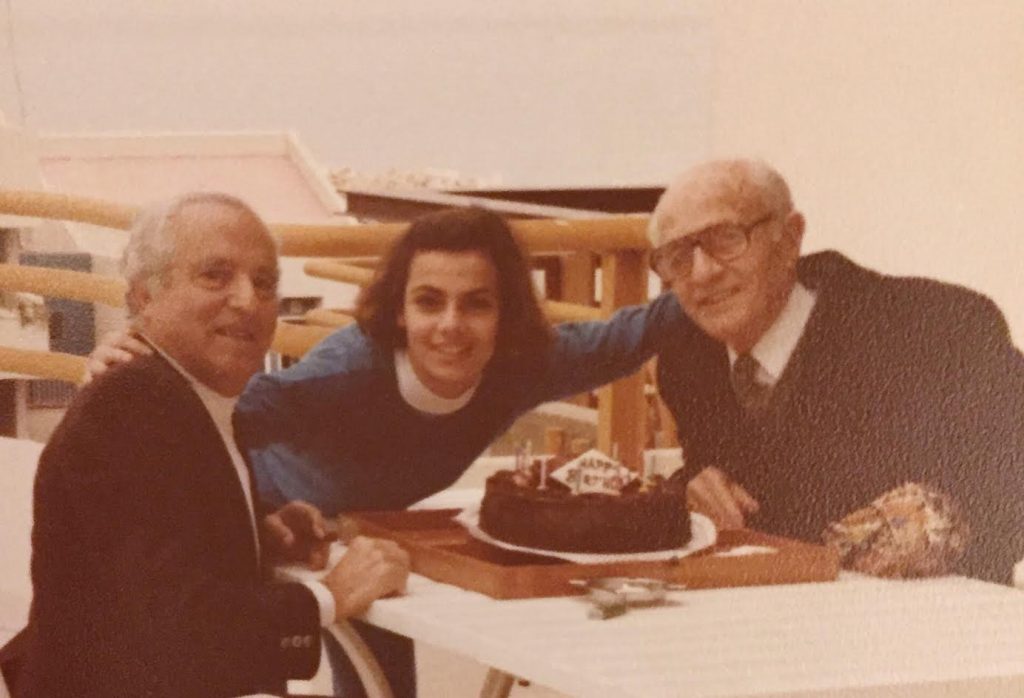

The author with both of her grandfathers on her 12th birthday. Both survivors of the Armenian Genocide, Haroutiun Arabian from Muratça is on the left and Lutfig Frankian from Diyarbakir (Dikranagerd) is on the right. (Photo courtesy of Paola Kassabian)

One evening in Aug. 1915, the Ottoman army came for the Armenian women and children of the village. My eight-year-old grandfather Haroutiun, his four-year-old brother Panos, their newborn baby sister, mother Zarouhi and grandmother had to leave their home overnight and walk 76 kilometers (nearly 48 miles) to the nearby town of Bilecik, where the entire Armenian population of the province was gathered. From Bilecik they walked to the next town, Eskisehir.

From Eskisehir they continued walking for months and for over 1,400 kilometers (nearly 900 miles) through Konya, Adana, and Ayntab, along the way adding more starving and scared Armenians to the group. On this one-way death march, Haroutiun remembers his mother carrying his baby sister who would cry of hunger. His baby sister eventually died of starvation in his mother’s arms, but Zarouhi refused to let go of her dead baby’s lifeless body. Zarouhi died soon after from exhaustion and starvation. My grandfather recalls seeing the burning body of his mother with his baby sister still clinched in her arms.

This is not a sight most of us can imagine or march away from.

Those who survived the long journey south reached Raqqa, Syria. According to my grandfather, this is where the real horror began. The two brothers, Haroutiun and Panos, now orphaned, lived on the streets of Raqqa all alone. They lived on the streets, slept on the streets and in the nearby woods, begged for food and money and stole whenever begging was not fruitful. But Haroutiun and his younger brother always managed to stay together. And survive. Their survival was not just personal, yet the survival of my family and ultimately our people. As eloquently stated in William Saroyan’s poem, he eventually would find another Armenian and create a new family.

Amongst all the hate and terror there was also goodness. The Near East Relief Society saved the orphans around 1919 or 1920, and they were taken to the Camp of Nahr Ibrahim. After surviving yet another horror—the malaria outbreak of 1923 claimed the lives of nearly half the orphans—Haroutiun and his brother Panos were transferred to a new orphanage in Jbeil called Trchnots Puyn (Birds’ Nest), run by a Danish missionary. In this orphanage, Haroutiun learned the art of shoemaking.

Haroutiun worked hard the rest of his life. This is all he probably really knew- to work hard and survive. He worked hard for many years and finally was quite successful and owned his own tannery in Beirut, Lebanon. He went from being an orphan learning the trade of shoemaking to becoming the owner of an entire leather factory. This is the Armenian will and spirit. This spirit, I am sure, is borne in each of us and further strengthened into our souls by the very enemies who have wished to see us annihilated.

My grandfather eventually carried out Saroyan’s prediction and married another Armenian and had four children and ten grandchildren. He lived a content life, but always had two recurring nightmares. The first involved the memory of the night the Turkish soldiers took him and his family out of their home and onto what would later become the death march; the second was the sight of his mother and baby sister burning.

My grandfather had nightmares about these dreadful events for the rest of his life. Although I cannot see this dreadful sight, I will continue Haroutuin’s fight to survive. No relocation, death march, or Genocide will extinguish this Armenian spirit.

I am Haroutiun.

Source: Armenian Weekly

Link: I Am Haroutiun: A Story of Survival