From the Armenian Weekly 2017 Magazine Dedicated to the 102nd Anniversary of the Armenian Genocide

Thursday was a school day in Chunkush. The children who normally filled its streets with laughter were instead busy with their lessons.

In the village center, a shopkeeper sold yarn to a customer. A few young men lingered outside a dry goods store. And a pair of mostly even-tempered state security agents shadowed me. Otherwise, the streets were empty.

Ulash Altay plays on a tree in the garden in front of his home in Chunkush. Ulash is a descendant of the only known genocide survivor of Chunkush (Photo: Matthew Karanian)

It would have been easy to bypass Chunkush. I suspect that most travelers don’t give this village a second thought. But most travelers in this part of the world aren’t interested in Armenians, either. I was traveling with a small group of Armenian scholars for whom Chunkush is a gem among the treasures of Armenian history.

Chunkush sits in the remote hard scrabble landscape between Kharpert and Diyarbakir. This village was, until 1915, part of the fabric of Western Armenia. Today, it’s largely unknown to outsiders.

Armenian Chunkush had existed almost since forever and was destroyed in a moment in 1915. Ten thousand Armenians—the entire population of the village—were killed. The region around the village became a mass grave.

It has now been 102 years since the start of the genocide known to many as the Armenian Holocaust, and identified by most Armenians as the Medz Yeghern, or Great Crime. After all this time, Chunkush still exists. But today it is a Kurdish-populated village in Turkey. Chunkush has been mostly cleansed of its Armenian identity.

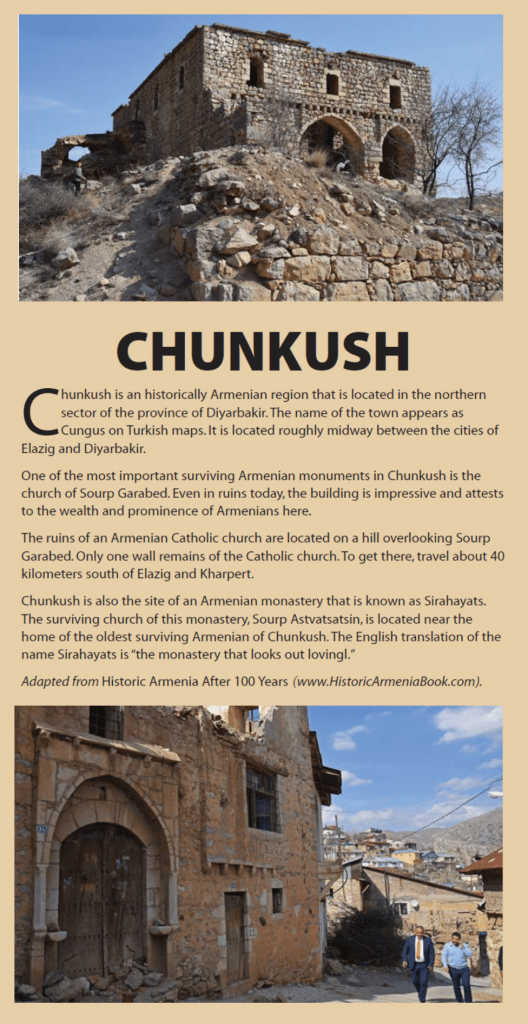

I had first visited Chunkush in 2014 to see what was left of our Armenian cultural heritage. I saw the ruins of a monastery, two churches, and a centuries-old neighborhood.

I returned in 2017 to see who was left. Chunkush is home not only to the ruins of ancient Armenian buildings. Chunkush is also home to a family that is descendant of a survivor of the Armenian Genocide.

This is how I met Ulash Altai.

Ulash Altai is an 11-year-old boy who lives in Chunkush with his mother and grandmother. His father had been part of the household, too, until his death a few months ago.

When I met Ulash on that Thursday morning in March, he told me that he would celebrate his 12th birthday the very next day. He was supposed to be in school, but on this day, the day before his birthday, he had left school early. He had learned that a group of Armenian Americans was visiting his grandmother. He wanted to be home to meet us.

Ulash isn’t a teenager yet, and he didn’t quite have the maturity to say this. But I would like to suppose that Ulash wanted to meet us for many of the same reasons we had wanted to see his family. I would like to believe that he wanted to learn about his past, that he wanted to start building a bridge to his future.

For the past two decades, I have traveled throughout Western Armenia to document the remnants of our homeland. I’ve recorded our churches, our forts, our ghost towns. But it was not until I met young Ulash that I really appreciated how bridge building has also been a significant, even if unintended, part of my research trips.

When we Armenians visit Western Armenia, we don’t go as tourists. We don’t go to have fun. Instead, we go to learn about our past and to see where our grandparents were from. But we accomplish much more than this. We also build bridges to the future with the people who today live in our homeland.

These people, sometimes Kurds, sometimes Turks, are some of the people who use our churches as barns and warehouses. These are the same people who might be tempted to see Armenian ruins as quarry material or as the locations of phantom buried treasure.

And sometimes the people we meet are the so-called “Hidden Armenians” of Turkey. These Hidden Armenians may be full-blooded Armenians who have converted to Islam. Or they may be Turks and Kurds who recall that they had a grandmother who was Armenian.

Our presence, even if brief, is a reminder that we care about our homeland and that we care about the welfare of the Armenians who still live there—whether they are Christian or not, and whether they call themselves Armenian, or not. Our presence in Western Armenia, even if for only a day or a week, is a reminder to the local residents of our shared past.

In Chunkush, this shared past includes Sirahayats, an Armenian monastery, and its surviving church, Sourp Astvatsatsin. The English language translation of Sirahayats is “the monastery that looks out lovingly.” This monastery is located on a hilltop just a few hundred feet from the home of Ulash. I imagine that the ruins of Sirahayats do indeed look out lovingly on Ulash’s modest home.

It was near this monastery a few years earlier that members of my group of Armenian American scholars had first met Ulas’s father. While in the nearby town square, a middle-aged man from Chunkush had approached them. “I see that you’re interested in old Armenian history,” he observed. He said this in Turkish, or at least he said words to that effect. “Well then, you should meet my mother in law.”

This man’s name was Recai. He was a stranger and he could have been many things, but he wasn’t a liar. He really did have a mother-in-law. Her name was Asiya. And, it also turns out, she really was old and she really was Armenian. Her role in the history of the Armenians of Chunkush was more than we could have imagined.

Asiya pauses with her grandson Ulash, during a visit from the author. Ulash is the sole surviving son

of Recai Altay, a Kurdish activist who was killed while incarcerated in Turkey last year.

(Photo: Matthew Karanian)

Asiya had been born in Chunkush in 1920.

At the time of Asiya’s birth, her mother was a 15-year-old genocide survivor—she was born in a town near Chunkush and was the only known survivor of the genocide who was still living in Chunkush. Five years earlier, during the summer of 1915, when the appointed time for killing the Armenians of the Chunkush region had been reached, Asiya’s mother had been 10 years old.

This little girl was standing alongside her neighbors, at the edge of a precipice, waiting her turn to be bludgeoned and pushed into the seemingly bottomless pit known as the Dudan Gorge. Locals today recall the Dudan Gorge, which is located a short march from Chunkush, as the place were 10,000 Armenians fell to their deaths.

This 10-year-old girl waited, but her turn to die never arrived. Instead, she was spared by a Turkish soldier who took pity on her, and who snatched her from death. He took her as his child bride.

Within just five years, roughly the time it took for that 10-year-old Armenian girl to mature, that Turkish soldier would become Asiya’s father.

Asiya’s long life has been marked by two traumas: first from the fear that she would be victimized because of her Armenian heritage; and second from her knowledge that her father had participated in killing every Armenian in Chunkush—every Armenian except for the girl who would become her mother.

Asiya is nearly 100 years old now, and for almost a century, her Armenian heritage has been perhaps the worst-kept secret of Chunkush.

Her son-in-law Recai—Ulash’s father—was killed last year. Sources describe him as a political prisoner who had been serving time for his support of Kurdish issues. A bomb—some say an ISIS bomb—struck his holding cell.

Now his son Ulash is his family’s bridge back in time to the world that existed in 1915, the time when Ulash’s great grandmother stepped back from the abyss, literally, to survive the genocide.

Sirahayats, the ancient Armenian monastery that looks out lovingly at Ulash’s home, is today at risk of destruction.

So also is Sourp Garabed, the grand cathedral that is close to the center of the village.

Asiya pauses with her grandson Ulash, during a visit from the author. Ulash is the sole surviving son of Recai Altay, a Kurdish activist who was killed while incarcerated in Turkey last year. (Photo: Matthew Karanian)

Is it reasonable to expect that Ulash’s appreciation of his ancestry, encouraged by his grandmother, and also by visits from Armenians, may inspire him to take a stand to protect these sites? I believe it is.

People such as Ulash may even take a stand to protect the Armenians in their midst. If this happens, then we Armenians will have helped to build the most important bridge of our time.

Source: Armenian Weekly

Link: Karanian: Building Bridges in Western Armenia