From the Armenian Weekly 2018 Magazine Dedicated to the Centennial of the First Republic of Armenia

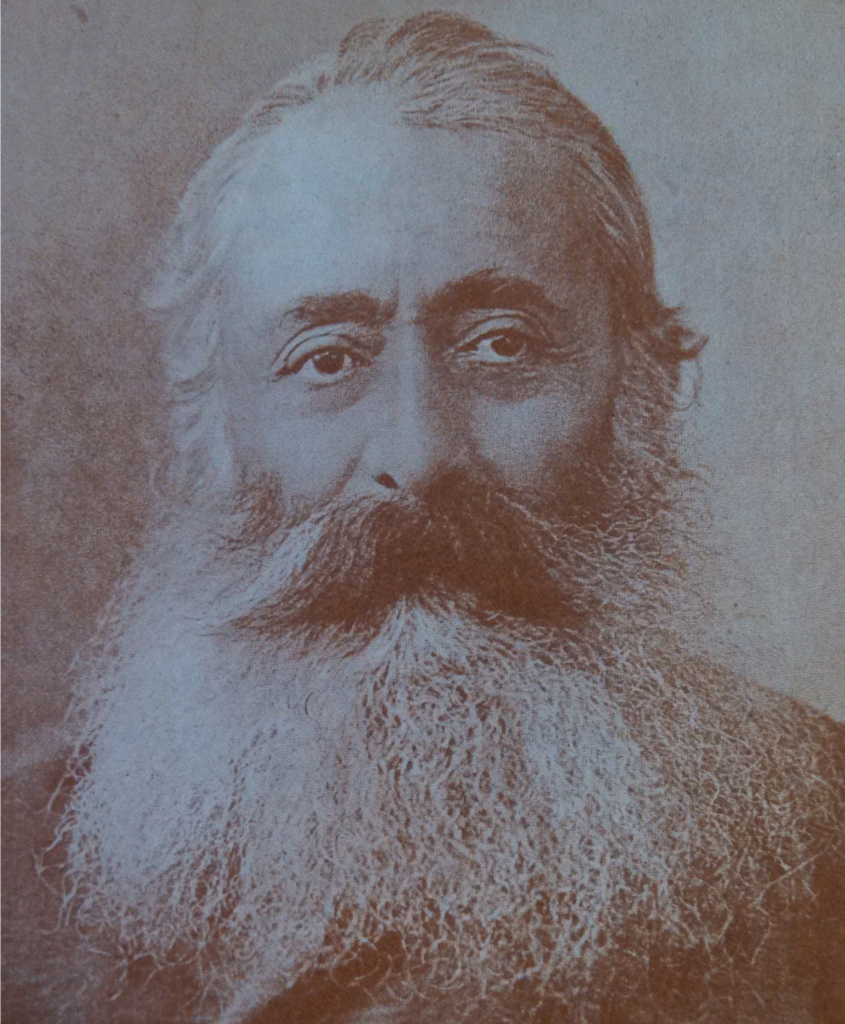

“Hidden venereal diseases[1] have begun to spread also among us, as they were spread in Russia and Europe. Syphilis[2] has already spoiled the pure Armenian family and threatened to destroy the Armenian home. Immigrant life, conscription, labor in big cities are to be blamed. Continually, Baku is ruining Armenian youth and dispersing them into small towns and villages inhabited by Armenians. Armenian young laborers infected with dangerous diseases are returning from Baku, Tbilisi, and Russia to the homeland and bringing with them this illness and contaminating the Armenian family,” doctor Vahan Artsruni[3] writes in the introduction of his book Vat Tsav (Bad Pain), published in 1900.[4] That book is one of the first published in Armenian that raises the question of venereal disease and the problems it caused among Eastern (Russian) Armenians at the beginning of the 20th century.

Having received his medical education in France, Artsruni was well aware of the harmful consequences of venereal diseases, which had already caused significant damage to Europe. He was also aware of the poor sanitary and health conditions of Armenians in the Caucasus. The first clinic in Eastern Armenia had opened in Artashat only in 1887, and another had been established in Yerevan in 1890. The first hospital in Yerevan had opened its doors in 1882 and had just 12 beds.[5]

In the early 20th century, the term “venereal disease” was known among Armenians as frankakht (French disease) or vat tsav (bad pain) and referred mainly to syphilis, gonorrhea, and chancroid, which were the most prevalent diseases of this kind. The three forms of venereal diseases identified in the early 20th century were known to produce superficial or visual symptoms on the exterior of the body, such as rash, warts, lesions, mucous, bumps, and various other forms of presentation. In fact, the symptoms of syphilis, its mode of transmission, and its effects on the body have been understood for hundreds of years.[6] At the end of the 19th century, Armenians, as other peoples in the region, were suffering from several well-known infectious diseases. In those conditions, when malaria, typhus, and cholera were also rampant, the question of venereal diseases was assigned secondary importance. Another reason was the shame and social stigma associated with these types of diseases among Armenians. Because of shame, ignorance, and a lack of education among the population at large, syphilis was neither prevented nor treated, and within a short period it became widespread and manifest.

As Artsruni points out in his book, the main population infected by venereal diseases consisted of Armenian migrant workers who were leaving their villages and going to large cities in search of work and money. In due course, those men’s tastes changed, they became accustomed to city life, and they adopted the habits of urban lifestyles, including abusing alcohol and visiting prostitutes. As a consequence, they were returning home infected with diseases. In conditions of poverty, many villagers had only one outfit and ate from a communal pot, and often slept in the same bed, all of which contributed to the rapid spread of disease. Another reason for venereal infections was ignorance about disease itself. There was no limiting of contact with the infected. On the contrary, workers coming back from the big cities married village girls; as a consequence, not only their wives but also the children born of those marriages suffered from disease. There were not enough doctors, and the absence of female doctors made the situation even worse. Venereal diseases cast substantial shame on a family, and especially female members. These women, with the help of their mothers-in-law, would try to find treatment for themselves and their children. Their best option was a village healer who would try to heal them using traditional methods. Those methods were not useful, however, and in most cases they cost patients their life.

But the situation was little better in cities. Women were afraid to seek out a doctor, afraid that their illness would be revealed, thus ruining “the good names of their husbands and families.”

“What is more preferable?” asked doctor Artsruni of his readers, “to cold-heartedly witness how people lose their health and keep silent, or to break the wall of false bashfulness and loudly pronounce the word ‘syphilis,’ which people have made synonymous with the word ‘disgrace’ against themselves.”[7]

How could the damage brought by venereal diseases be prevented, controlled, and cured? Ideas about public hygiene and attitudes about morality found their way into Armenian society through the publications of Armenian physicians. With his publications, Artsruni tried to support Armenian women and girls who were victims of a patriarchal society and of social stigmatization. In 1901, he published another book, this time about marriage. In it, he terms any man who would ignore his venereal disease and marry an innocent girl a “monster.” [8] He notes that these men are guilty in front of not only their wives but also an entire generation that they have poisoned. He titled the eighth chapter of the book “Syphilis,” in which he tried to explain the disease and treatments for it.

Artsruni’s professional life was significantly influenced by French dermatologist Jean Alfred Fourier[9], who specialized in the study of venereal diseases. “How to stop syphilis? How to treat it? Of course, with the help of doctors, and never old quack cures of the village,” Artsruni wrote.[10] Concerning treatment, physicians at the time were divided into two camps. One argued for treatment using mercury, the other for non-mercury therapies. Artsruni was more inclined toward mercury treatment, but he warned patients that a full and absolute cure would not come immediately: It may take a year or sometimes three years, and they had to have patience. Writing about the inheritability of syphilis and its destructive effects, Artsruni notes that everyone who has syphilis should visit a doctor and get married only with the doctor’s permission. “Undoubtedly, the time will come when it will be necessary to produce health certificates from doctors to get married”: That is required for honesty; for the health of the family and offspring; the survival of the nation; and, it should be added, because people are selfish even in marriage, and so it is a necessity for their own happiness, he argues.[11]

reads “What is health science?”k

Not finding allies among men, who were continuing marriages without proper treatment for syphilis, Artsruni tried to find allies among women and girls to save them from danger. In 1903 he published another book, dedicated to his niece, Haykanush Tigranian.[12] In it, Artsruni notes that “the Armenian girl should constitute a pillar of the family, but her education is wrong and full of false influences.”[13] He criticized the traditional way of girls’ education and their treatment as unimportant, secondary members of the family, which undermines the strength of the Armenian nation. “She should publish good books, establish children’s journals, spread positive education among the nation. She is also a part of our nation, isn’t she? Society has expectations from her. She should act—act in all spheres,”[14] Artsruni writes. Referring to marriage, he points out, “An Armenian girl is given to a husband; she does not choose him.”[15] He calls on girls to resist such brutality and marry only with love. He also warns girls to pay attention to their future husbands’ health condition before agreeing to the marriage.

Elsewhere, his contemporary, Dr. Budughian, writes that “to be safe from syphilis, merely awareness is needed. If the child were to receive education within the family similar to that at school, it would give hope that syphilis will gradually diminish. Otherwise, degeneration is inevitable.”[16]

Despite the efforts of Armenian doctors, the disease continued to spread. It was necessary to take more practical steps. The situation in Europe was no better. According to Fournier, who was the first professor to obtain a chair in both dermatology and the study of syphilis in France, there should be three paths of action: (1) to put into effect administrative measures and policies affecting the public and having as their goal to stop the spread of syphilis; (2) to attack syphilis by treating the disease; and (3) to fight syphilis by educating the younger generation of physicians on all aspects of the disease. In addition to that three-pronged policy of treatment and education, Fournier added another measure: marriage. “Nothing more noble, nor more exalted than to pursue the extinction of syphilis by the early unions, the marriages at the age of 25 between a husband and a wife, equally chaste, equally dignified, one to the other as the flower of the orange blossom.”[17]

At the time, France was trying to control the situation by monitoring the health of prostitutes, which was neither fair nor effective. Police checked prostitutes and regularly demanded health certificates, although they never asked the same of men who frequented brothels. But even that unequal and unfair method could not work in the case of the Armenians. They did not have any authority to establish control over brothels in the large cities of the regions. Their only hope was the Catholicos of All Armenians, in Etchmiadzin, who was at that time Mkrtich Khrimian (Khrimyan Hayrik). A group of Armenian doctors, among them Artsruni, introduced the problem to Archbishop Sedrakian, who was a confidante of Khrimian. The Catholicos understood the seriousness and urgency of the question and immediately took action. In 1904 he issued the Edict on Marriage, according to which every man should provide a certificate from a doctor about his health to a priest before the wedding ceremony in church.[18] According to other Armenian sources on the issue, for some time the “Marriage Certificate” worked efficiently, and the population supported the decision of the Catholicos. The problem came back again, however, and the number of those infected increased during World War I and the Armenian Genocide.

In 1917, a Dr. Makarian raised the question of prevention of venereal diseases: “Not only the individual but also society, the government, must fight against such infection. But to succeed in this fight, it is necessary to eliminate the attitude society has in general about venereal diseases. We need to cast aside prejudice, start talking and writing about syphilis freely, tell the people the nature of it, and teach them how to combat it successfully. It is essential that venereal diseases and especially syphilis come out from their covered, hidden state, and we begin to fight against it as freely as we fight other infectious diseases. This is the only guarantee for a successful outcome.”[19] But, unfortunately, the call of doctors regarding the urgency of the problem would not be heard. Armenians and the entire region were suffering from war and other well-known dramatic events. There was no time for fighting venereal disease.

Armenian doctors revisited this issue only during the First Armenian Republic. At the beginning of its establishment, the young republic established the Ministry of Relief, which was supposed to deal with the health issues of the republic. Through the efforts of the ministry, the Armenian Physicians’ Congress was organized in 1920. Its primary purpose was to combat malaria, but during its various sessions other health issues of the Republic were discussed, including venereal diseases. This ministry was abolished in Jan. 1921 by a parliamentary decision.[20]

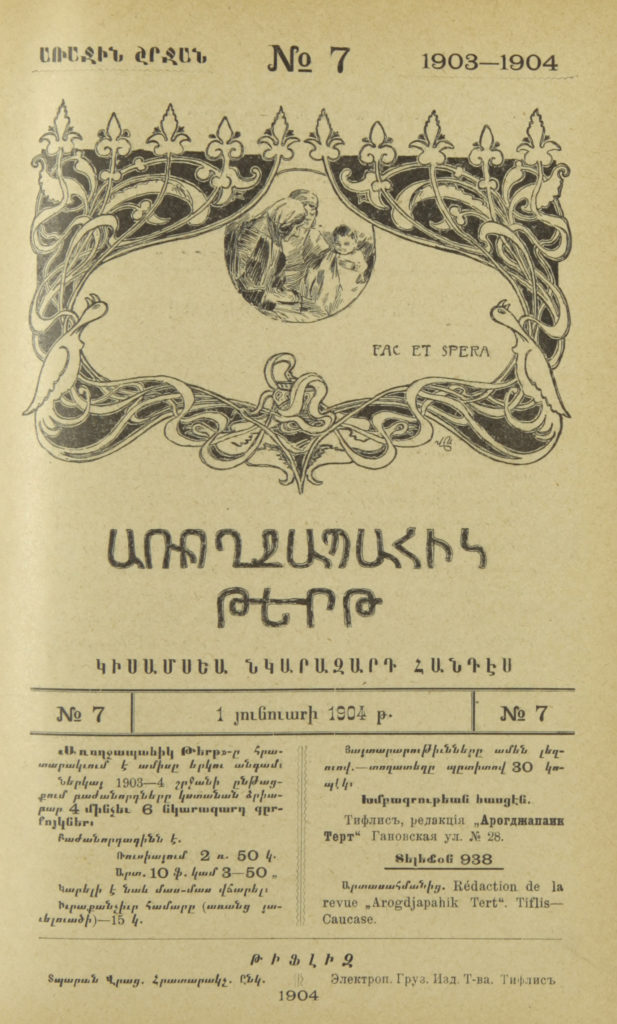

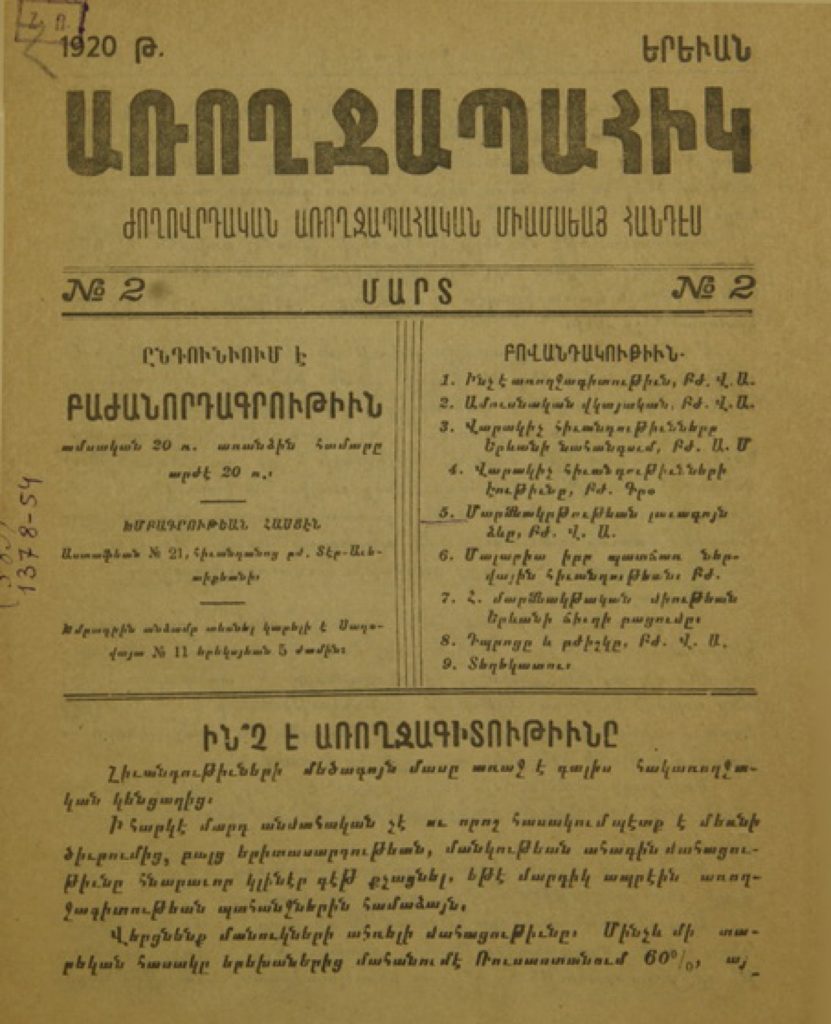

Artsruni was more enthusiastic and motivated in his mission and work because of the long-awaited independence of Armenians. Now he had an opportunity to act freely for the benefit of his nation. In Feb. 1920, with the help of his friends, he began publishing the first health journal in Armenia. The first article of the inaugural issue of Aroghjapahik (Healthcare) was dedicated to the prevention and treatment of venereal diseases. “The government takes measures,” writes Artsruni in it, “but they are not enough if there is no public support. The government urges us not to keep infectious patients at home, but to take them to hospital and ‘isolate’ them so that they cannot infect others. But what use is that if the people continue to hide their infection?”[21] The journal aimed not only to educate the people but also to dispel thousands of superstitions, to warn them not to trust village remedies. Especially in light of the genocide of Ottoman Armenians, the future and the existence of the Armenian nation and its young independent republic were dependent on a healthy society. At least, that was Artsruni’s conviction: “We need a healthy generation in body and in soul, which can only be born to healthy parents,”[22] he wrote.

Artsruni used the journal platform to raise the question of a “Marriage Contract” once more. He reminded his readers about the famous Catholicosal Edict of 1904 and pointed out that it was not working anymore. He also considered it “incomplete,” because a health certificate was not required of women, it was required of men only, which made it entirely insufficient. “Khrimian’s great work should be implemented through legislative means. Let the parliament of Armenia develop this law as soon as possible, and the homeland will be grateful for it,”[23] he wrote.

It is not known whether the Armenian parliament managed to discuss the question, and a relevant law was not adopted during the short-lived First Armenian Republic. One thing is certain, however: Soviet Armenia was fighting venereal diseases for several decades after its establishment.

Notes

[1] The term “venereal disease” refers to a group of illnesses that enter the body through either sexual transmission or blood transfusion. The word “venereal” itself refers to activities involving sexual desire or sexual intercourse in general. For more see: Wills, Mildred F., “Our Attitudes toward Venereal Disease Nursing,” The American Journal of Nursing 52(4), 1952, p. 477.

[2] Syphilis is one of the oldest known venereal diseases and can manifest itself in various ways throughout the body, and is capable of changing into different, more complex forms over time.

[3] Vahan Artsruni (1857-1947) was a well-known Armenian doctor who graduated from the school of medicine at the University of Paris and was a member of Caucasus Doctors Union. He edited and published medical journal “Aroghjapah tert” [Healthcare newspaper] in Tbilisi (1903-1905) and “Aroghjapahik” [Health-care] in Yerevan (1920).

[4] Artsruni V. Vat Tsav [Bad Pain]. I. Syphilis (translation), II. Chancre Mouth, III. Chlamydia, Tbilisi, Publication Mn. Martiroseants, 1900.

[5] Armenia in 1870-1917, in The History of Armenia, Vol. VI, published by the Academy of Science of ASSR, Yerevan, 1981, p. 959.

[6] Cooper, Alfred, Syphilis, Second edition (Philadelphia: P. Blankiston, Son & Co., 1895), pp. 1-2.

[7] Artsruni V. Vat Tsav, p. 10.

[8] Artsruni V., Amusnutiun: Aroghjapahakan Etude [Marriage. Healthcare Étude], Tbilisi, 1901, p. 96.

[9] Jean Alfred Fournier (1832-1914) was a professor of dermatology at the University of Paris and director of the internationally renowned venereal hospital at the Hospital of St. Louis. He wrote extensively on the clinical and social aspects of this subject. Fournier emphasized the importance of congenital syphilitic disease and wrote on its social aspects (Syphilis et Marriage, 1890).

[10] Artsruni V., Amusnutiun, p. 130.

[11] Artsruni V., Amusnutiun, p. 132-133.

[12] Artsruni V., Aghjik (Aroghjapahakan ev Baroyagitakan Etude) [Girl (Health and Ethics Étude)], Vol. I, (Georgian Literature Company; Tbilisi, 1903).

[13] Ibid., p. 4.

[14] Ibid., pp. 11-12.

[15] Ibid., p. 66.

[16] Budughian A., Aroghjapahakan Nver Norati Kanants [A Health Offering to Young Women], (Printing house Stepaniants, Alexandropol, 1901), p. 72.

[17] Tilles G., Grossman R., Wallach D., “Marriage: A 19th Century French Method for the Prevention of Syphilis: Reflections on the Control of AIDS,” International Journal of Dermatology, Oct. 1993, 32 (10) p. 767.

[18] Aroghjapahik journal [Healthcare], (publisher: Aghbyur-Taraz, Tbilisi, 1910) No. 76, pp. 5-6.

[19] “Aroghj kyank,” Joghovrdakan Aroghjapahik Amsatert [“Healthy life.” Popular Health Monthly], (publisher: N. Yerevantsian, No.1, Baku, Jan. 1917), pp. 26-30.

[20] Khatisian Al., The Founding and Development of The Republic of Armenia, (Hamazgayin: Beirut,1968), p. 146. Vratsian S., Republic of Armenia, II edition, (Printing house Mush: Beirut, 1958), p. 364.

[21] Aroghjapahik [Healthcare], No. 1, (Yerevan: Feb. 1920), p. 3.

[22] Aroghjapahik, No. 1, p. 4.

[23] Ibid., No.2, p. 23.

Author information

The post Marriage Contract: Armenians against Venereal Diseases at the Beginning of the 20th Century appeared first on The Armenian Weekly.

Source: Armenian Weekly

Link: Marriage Contract: Armenians against Venereal Diseases at the Beginning of the 20th Century