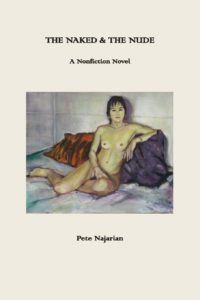

The Naked & The Nude: A Nonfiction Novel

By Pete Najarian

Regent Press (June 30, 2017), 454 pages

ISBN-10: 1587903954

Paperback, $25

Pete Najarian’s The Naked & The Nude (Regent Press, 2017) is a nonfiction novel that tells the story of an artist, the son of immigrants, in pursuit of the dream girl he hopes to marry and have children with. Besides satisfying his “usual lust,” marriage, the artist believes, will give him the home he had lost in a “fatherless America.”

“Crippled” for life, when his father was crippled when he was only three, the son longs to be whole again, yet seems doomed to spend a lifetime “separate and alone.”

The book is the third in a trilogy of nonfiction novels Najarian started writing in the summer of 1992. In all three, the narrator is the same fearful and shy artist “fac[ing] the world that was never home.” “My subject has always been the same,” notes Najarian. “It is essentially autobiographical.”

Initially interwoven, the novels were eventually published in three separate volumes: the 2010 The Artist and His Mother (Fresno University Press), the 2014 The Paintings of Art Pinajian (Regent Press), and the 2017 The Naked &The Nude.

Much like his predecessors, the narrator is plagued by his inability to hold on to what might help fulfill his vision. His “Why couldn’t I stay in Kansas and marry her and have the home and family I longed for?” sums up a lifetime of continuous “loss and regret.”

Unlike his predecessors, however, the questing artist has a self-consciousness and a self-confidence lacking in his earlier counterparts. While still “longing for a woman and a home,” he is now able to escape his loneliness by returning “to the road” where he felt tranquil and safe. “The road had become so familiar by now I felt I could go anywhere,” writes Najarian.

Ultimately, he transcends his own misery and connects to the pain of humanity through the universal language of music. His “song of my longing” may be a melancholy song, but it is a song “even wolves and whales will sing when they lose each other and search for home.” Najarian ends his book with “the old cripple” saying through Brahms’s First Symphony, “the greatest of all symphonies,” that “there would be no more elegies but only triumph and apocalypse.”

Also gone in this third book are the apologies and the endless expressions of gratitude for favors bestowed on Najarian by his friends. His usual, “For Arpi, with many thanks,” has changed to, “For Arpi, with love.”

The Naked & The Nude tells “my same old rejection story” through encounters with models (a few too many perhaps?) the artist keeps drawing to find his visionary girl. Just when he runs the risk of repeating himself, however, Najarian shakes the reader awake with the stunning accuracy of his observations. As he sketches the backyard outside his classroom at Oakland International High, where Najarian still subs, “It was a dismal scene of concrete and chain link, but drawing could transform even a prison into Eden,” he writes. Elsewhere, on the long bus ride to Tijuana, “I returned to my copy of Don Quixote while an old woman sat beside me holding a live chicken.” Najarian appeals to the reader with the haunting beauty of his writing: “and losing her balance she [his mother] fell and broke her hip, and it was like a bolt of lightning that had split an old oak tree.”

In addition to being about “the women in my life,” the elegant volume is social and cultural history. The sexual revolution and the anti-war politics of the ’60s, the Free Speech Movement at Berkeley, the women’s movement of the ’70s, the new films, casual encounters with artists and the authors whose books Najarian was avidly reading as they came out, are seamlessly integrated into his story: “That’s De Kooning over there”; “Tim led me to the White Horse Tavern where he had drunk with Mailer”; “In the meantime, back in the States, Marilyn Monroe killed herself in her own kind of sickness.”

To be sure, some will be turned off by Najarian’s explicit descriptions of his sexual experiences. “I wanted to write about the women in my life,” he explains. “They are all real.” He is quick to add, however, that the Nude is an art form invented by the Greeks in the fifth century B.C., different from the Naked, which refers to a human being. Indeed, what the reader leaves with are the vivid reproductions in the book of his nudes and his landscapes, and not, to borrow his words, the “disgusting lecher” who sleeps with one woman after another.

Najarian does not quite achieve his vision of wholeness, but he is no longer the mournful son of the first book of the trilogy, in search of the mother who alone “seemed to tie him to this planet.” Nor is he the wronged cousin of the second book, fuming with anger over his family’s betrayal. He now “hitch[es] across the continent so alone yet unafraid on the dark highway.” He also loves being surrounded by his students at the Oakland Unified School District. The fatherless cripple can, in fact, affirm as never before, “Something kept me alive…. I whistled my Scheherazade to the silence of the stars…until the silence would hug me like a father and I would never be afraid again.”

Nonetheless, the question remains: Does the little boy become the man he prays to become? And if, as he muses to himself at the close of the book, “You’re not a cripple…you never were a cripple, let go your fear and dance the dance of the ages, let go, let go,” why the reluctance almost to “let go” of “the sickness that would plague me for the rest of my life?” Are the fear and the alienation of life in exile the indelible scars left by “the nightmare of history?” Or are they, perhaps, evidence of a life lived to the full? There are no plain answers here. Only more questions.

Source: Armenian Weekly

Link: Pete Najarian: Still Chasing but Not Catching