Special to the Armenian Weekly

I don’t know whether it was a fluke or by design, but the Armenian Weekly’s Aug. 26, 2017 issue included three articles about the role Armenian-language knowledge plays—or doesn’t play—in one’s Armenian identity: Marie Papazian’s “A Generational Question: ‘If You Don’t Speak Armenian, Are You Really Armenian?’”; Garen Yegparian’s “Language vs. Spirit”; and Rupen Janbazian’s “‘Where Are You From?’ and the Huge Pile of Complexes.” Those articles were followed by the Weekly’s Oct. 6, 2017 online posting of Ani Bournazian’s “How Do You Measure Armenian Identity?” I read each with interest, and here I offer my reflections that resulted from those readings.

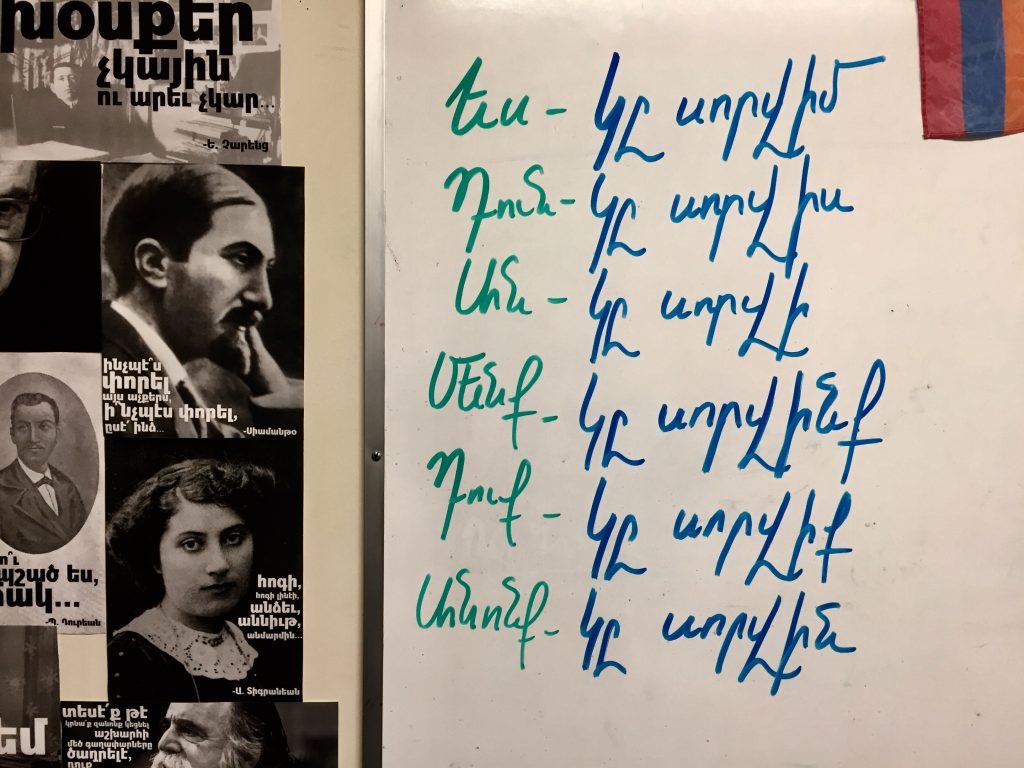

“The journey to language proficiency isn’t easy. But it’s worth taking, even as the journey starts with Armenian identity firmly in hand, head, and heart.” (Photo: The Armenian Weekly)

Although scholars conclude that national or ethnic identity is built on common touchstones—including language—we’ve reached a point in our corner of the Armenian Diaspora where Armenian identity does not require Armenian-language knowledge. We all know Armenian Americans who identified as Armenian but went from cradle to grave not speaking much Armenian at all. They experienced their Armenian ethnicity in a way that was different—but not quantitatively “better”—than an Armenian with Armenian-language proficiency.

In my third-generation experience growing up in an Armenian-American community, the very fact that we spoke a certain level and kind of Armenian informed and continues to influence a unique and beautifully fraught Armenian-American condition. And yet, Armenian identity survives, and people take the affirmative step of naming themselves Armenian, whatever their Armenian language skills.

But that’s not the end of the conversation. We have a problem. Too many have concluded that because Armenian identity survives a lack of Armenian-language knowledge, Armenian language learning is not necessary. It’s a reason why student enrollment in our Armenian-language one-day schools continues to decline steadily: Those schools increasingly have to cater to children who come to school already understanding the language; thus, unintentionally, they marginalize hundreds of non-Armenian-speaking children whose academic needs can’t be met well in today’s traditional Armenian school classroom.

When are we going to ask the question that we still haven’t adequately answered, even after all the years that have led us to today: How can we teach Armenian as a Second Language in a safe and systemic way and convince thousands of families that have abandoned the language to return to the classroom so that they and their children can deepen their Armenian experience, and in doing so strengthen the Armenian Nation?

The journey to language proficiency isn’t easy. But it’s worth taking, even as the journey starts with Armenian identity firmly in hand, head, and heart.

***

It’s Saturday morning, and I’m in class at Mourad Armenian School, Providence, R.I. My classmates are Armenian American-born peers and we are reading textbooks filled with many difficult and mysterious words not heard at home. We are among the last generation of children whose genocide survivor grandparents are living, so we hear Armenian regularly and even speak it to older generations. At annual year-end hanteses (concert), we recite poems and perform roles in plays, not completely understanding what we are saying and hoping we don’t embarrass ourselves and our families by stumbling and mispronouncing words in a language we have been taught is sacred and precious. A language whose erosion is a sign of assimilation, waste, and loss. We try to make our parents and grandparents proud.

***

I’m in Lebanon with five other college students from the United States who have been selected by the Eastern Armenian Prelacy to spend six weeks in Bikfaya learning Armenian language, history, and culture. Our stay has been underwritten by Kevork Hovnanian. A trip to Syria by way of Ainjar (Anjar) takes us to Aleppo, Damascus, Der Zor, and Kessab. In Aleppo, a fellow student and I are assigned to stay with a family that includes three sisters and a female visiting cousin. We seem to be interacting well and the family hosts us all for a pleasant dinner on our last night in the city. My roommate gets sick and goes to bed early. I follow later after everyone has left. The sisters and cousin crowd in the bedroom doorway. They ask me questions that I try to answer in my expanding, but still child-level Armenian. The atmosphere turns when the cousin responds, “Jib, jib, jib,” at my efforts and the mocking begins. I start to cry and tell them in Armenian that they’re breaking my heart, that we are the same, that we are all Armenian. But we are not the same and my baby Armenian words don’t move them. I tell them to leave me alone, and after they leave I weep for the loss of something I can’t identify.

***

I’m in Radnor, Penn., at the home of poet Vahe Oshagan and my fiancé, Hayg, son of Vahe and grandson of Hagop Oshagan, the revered Armenian literary critic and novelist. I’m listening very hard to Hayg’s conversation with his father, paying attention to words, idioms, inflections, and tenses, and saying as little as possible. I cannot participate fully in this high-stakes dialogue, full of nuance and fast and fluent observations in Armenian. I rehearse sentences and try to fit them into conversation when I can. I watch for signs and prompts. By the end of the evening, I’m exhausted. This construct repeats over the years.

***

It’s my wedding day, and I’m dancing with my new father-in-law at the reception. He asks, “You’re going to speak Armenian?” It’s a statement wrapped in a question. “I’ll try,” I promise in Armenian.

***

Hayg and I are walking back to our apartment on the University of Wisconsin Madison campus, and I’m three months pregnant with our first child. I have chosen this day to fulfill my promise to speak Armenian. This is the day I start to build the capacity that will allow Armenian to be the language of our home, the language of our family, the language of our firstborn. Hayg says something to me in Armenian and I respond in Armenian. And we continue from there.

***

After several weeks of conversation, my Armenian comes out of my mouth more fluently, if not always perfectly. I can better recall and use the Armenian words buried in my brain. I still talk to myself to practice what I’m going to say, to try out that more precise word, to elevate my expression. I make mistakes and feel anger and shame when corrected, but I carry on to keep the promises I’ve made to others and myself. For my family’s sake. For my sake.

***

Years pass and my Armenian is stronger. Vocabulary is situational, so mine revolves around home, school, work, and meetings. I’m conversant in Armenian, and know my share of 25-cent words. I read the Hairenik Weekly—using the Armenian school lessons of decades past—to build vocabulary or correct pronunciation of certain words, seeing the spelling. My children speak Armenian and attend Armenian school. For an Armenian whose family has been in the U.S. for nearly 100 years, I’m satisfied with my achievement, but never completely relaxed using the fruits of that achievement.

***

I’m at a community event that has babies and toddlers everywhere, and Armenian is in the air because Armenian is the language spoken to small children, by instinct and impulse. Pari (good), char (bad), yegour (come), voch (no), gatig (milk). In this moment, these are not baby words. They are gold among the tin of English. The Armenian words are few, but they are present and they resonate, said with love and memory. For some parents and grandparents, these words and others like them are all that is left to say. But they are beautiful and meaningful to the listening children who will only pass on these few remnants of Armenian themselves without more Armenian language learning opportunities.

***

I’m at Detroit’s Armenian Relief Society (ARS ) Zavarian Armenian School on opening day and see five-year-old Sevana Derderian enrolling for the new school year. It’s her first Armenian-school experience, and I watch her as I speak to her mother. There are few non-Armenian-speaking peers in the room, and the parents of Sevana’s friends have chosen not to enroll their children. I wonder how Sevana will feel about herself in the dynamics of a class filled mostly with children from homes where Armenian is spoken regularly. Will she crack a code that others already know innately? I silently make a wish that she won’t learn to connect Armenian-language learning with negative feelings that hurt her heart and spirit.

* * *

Xenoglossophobia. This is the fear of foreign-language learning. It’s my theory that thousands of Diasporan Armenians suffer from this phobia, which teachers of second languages debate and discuss.

University of Texas Austin foreign-language educator Elaine Horwitz says that, for many, foreign language learning can be filled with anxiety and can negatively impact learning.

“I think that there’s some amount of inherent anxiety in language learning, because A, it’s just difficult, time-consuming and complicated, and B, I think that for some people it’s a threat to our self-concept,” she told Inside Higher Ed. “We can’t be ourselves when we speak the language. We have to be limited just to whatever it is that we can say.”

Second-language scholar Alexander Z. Guiora has written that learning a second language is “a profoundly unsettling psychological proposition because it directly threatens an individual’s self-concept and worldview.”

Armenian-American parents who have bad memories of Armenian school and have not sent their children to avoid their negative experiences will recognize Guiora’s additional observation that students learning a second language—even when it is the language of their ancestors—“experience apprehension, worry, even dread. They exhibit avoidance behavior such as missing class and postponing homework.”

***

There has been much discussion in the Armenian press recently about reconciling differences between Western and Eastern Armenian and protecting Western Armenian generally as we continue reflecting on the meaning of our nationhood in the aftermath of the Armenian Genocide’s centennial observance and in the run up to the 100th anniversary of the first Armenian Republic’s establishment.

As a community and nation, we may also want to focus on the survival of Western Armenian’s use throughout the Diaspora and on ways to rebuild an Armenian-language learning infrastructure that will teach Armenian as a Second Language using a strong, relevant, and systematic curriculum that meets children where they are and builds to a satisfactory and satisfying language-proficiency level.

“One shot” classes that have Armenian as a Second Language learners for a year or two and disband because of teacher or student discontinuity, together with piecemeal approaches in integrated classrooms, only perpetuate both the current atmosphere of parent abandonment of our Armenian one-day schools and the derision and eye-rolling that greets the question, “Are you sending your child to Armenian school this year?”

Continuing patchwork solutions to halfheartedly teach Armenian to non-Armenian-speaking Armenian children will only continue to keep Armenian Americans away from most of today’s Armenian schools. Parents will not send their non-Armenian-speaking children to a place where their understanding of themselves as Armenian may be threatened. The emotional connection between the non-Armenian-speaker’s language-learning discomfort and their Armenian identity may create the conflation that leads to that destructive question: Am I a “real” Armenian if I don’t know Armenian?

The sooner we implement and advance an Armenian-language learning environment for non-Armenian-speakers that deepens their Armenian experience in a safe and supportive space, the sooner the lingering divisions in our communities based on language and experience with language will blur, especially as the influx of fresh native Armenian speakers diminishes throughout the eastern U.S.

Until that happens, old debate questions about identity and language will pit us against each other and serve as a distraction, until we come together and confront the real danger we face together: the absence of a meaningful plan to shape the destiny of Western Armenian’s relevance, learning and use in our eastern U.S. communities, and the mindset of too many Armenian Americans who have concluded in the full embrace of their Armenian identity that it is not worth learning and using the language of their ancestors.

The post Reflections on Armenian Language Learning’s Impact on the Armenian-American Experience appeared first on The Armenian Weekly.

Source: Armenian Weekly

Link: Reflections on Armenian Language Learning’s Impact on the Armenian-American Experience