This article is part of a continuing series documenting the available records for research into one’s Armenian family roots. Part I in the series supplied a historical background on the Armenian genealogy movement as well as specific records available for Syria. In Part 2, records from Lebanon and Israel were detailed. Part 3 covered the records of Greece and Jordan. Southeast Asia and Serbia were covered in Part 4.

Turkey

It has now been five years since I first wrote about the use of Ottoman-era population registers in Armenian genealogical research. What began as a limited effort at learning more about the family of my grandfather, from the Western Armenian village of Sakrat in the district of Palu, has turned into extensive research to delve as deeply into what is possible today and what might be in the future.

It is fair to assume that for most Armenian-Americans, like myself, the records pertaining to Western Armenia are of the highest interest, but many share the misconceived notion that all records pertaining to land now part of the Republic of Turkey have been destroyed and nothing more can be learned there about our family histories. But this is not entirely the case.

As was stated in part 1 of this series, new and important information about Armenians living within the Ottoman Empire is continually coming to light.

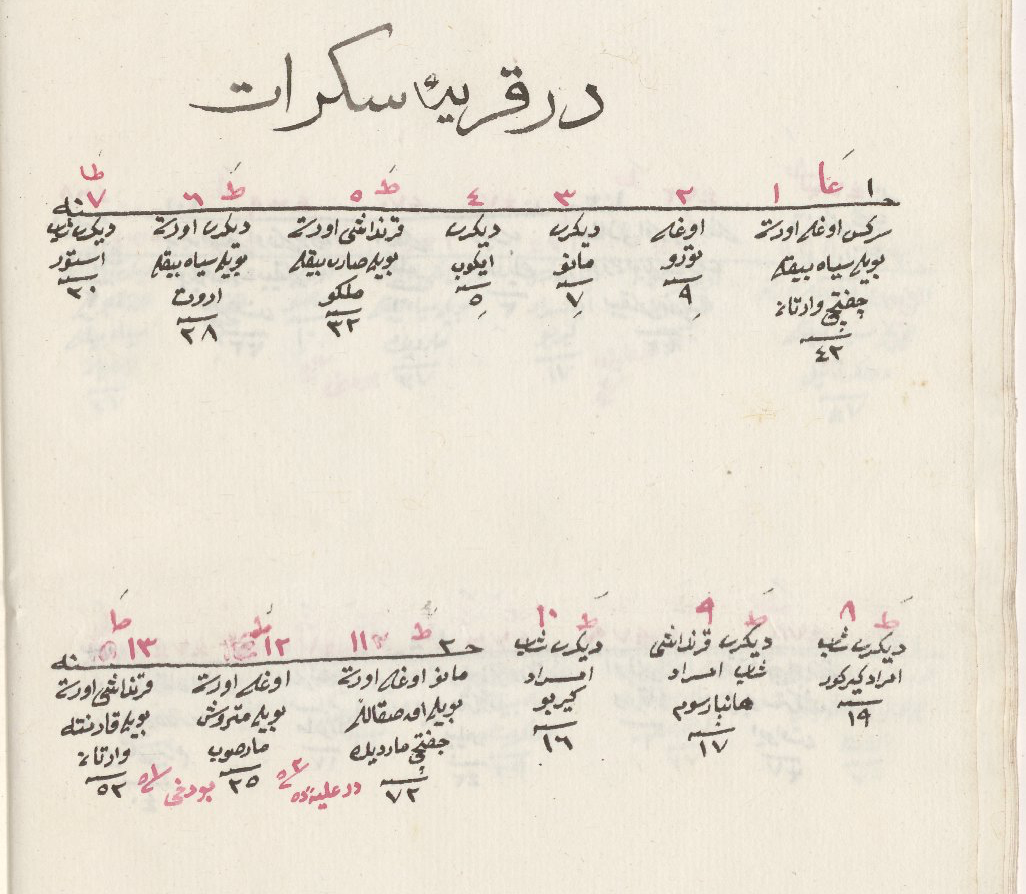

In part 2 of this series, I explained the extent of available Ottoman population registers for Palestine and in particular Jerusalem. Unfortunately, the same Ottoman-era information has not been made available in Turkey. The government of Turkey only allows access to Ottoman population registers, accessible in Istanbul and Ankara, for periods prior to 1880. Most of what is available for Armenian-inhabited areas are from even earlier time periods (mostly from 1830 to 1860). This makes it all the more difficult for Armenians, who are curious to uncover their family roots. Bridging the enormous 75-year gap between the available records and our recorded family histories is a nearly insurmountable task. And to add yet another layer of complication: the population registers list only men.

Yet despite these limitations, the information contained in the registers is valuable on many levels. My most extensive discussion of what can be achieved with this information can be found on Houshamadyan’s website. There, I was able to demonstrate the method for rebuilding family trees from the Armenian village of Hazari in the Chmshgadzak district. While the available records for Hazari made it somewhat unique, there are other locations offering similar opportunities.

It is indisputable that these registers have changed what is possible for Armenian genealogy and should the post-1900 data become available, even more can be achieved.

Last February, I detailed the Turkish government’s decision to release a new document called “Alt ÜSt Soy Belgesi̇.” The document, available to each Turkish citizen, will show their lineage as far back as has been linked through the government system. In general, current citizens have a greater ability to access information. This is not only an important development, but also the release of the “Alt ÜSt Soy Belgesi̇” may also signal a willingness to release the last Ottoman population registers upon which they are presumably based. This is long overdue as it has been over 100 years and other countries make such information freely available (for example, the U.S. releases census information after 72 years). The implications for uncovering Armenian ancestry have, thus far, been varied for a number of reasons, which I detail in greater depth in my article.

Before moving on from the available Ottoman records, it should be mentioned that a general search of the archives catalog can also yield results about particular families. Some of the more interesting finds are the photographs.

Beyond the Ottoman records, there do exist a number of Armenian church records. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) microfilmed the records that were available at the time in 1980. The records are cataloged on familysearch.org and can be accessed through the LDS Family History Library.

Unfortunately, Armenian Apostolic Church records have survived essentially for Istanbul and its environs. However, for Istanbul, the information is rich with the sacraments as well as a number of censuses. These censuses appear to be copies of the original Ottoman registers, so for these areas, we have more information available to us.

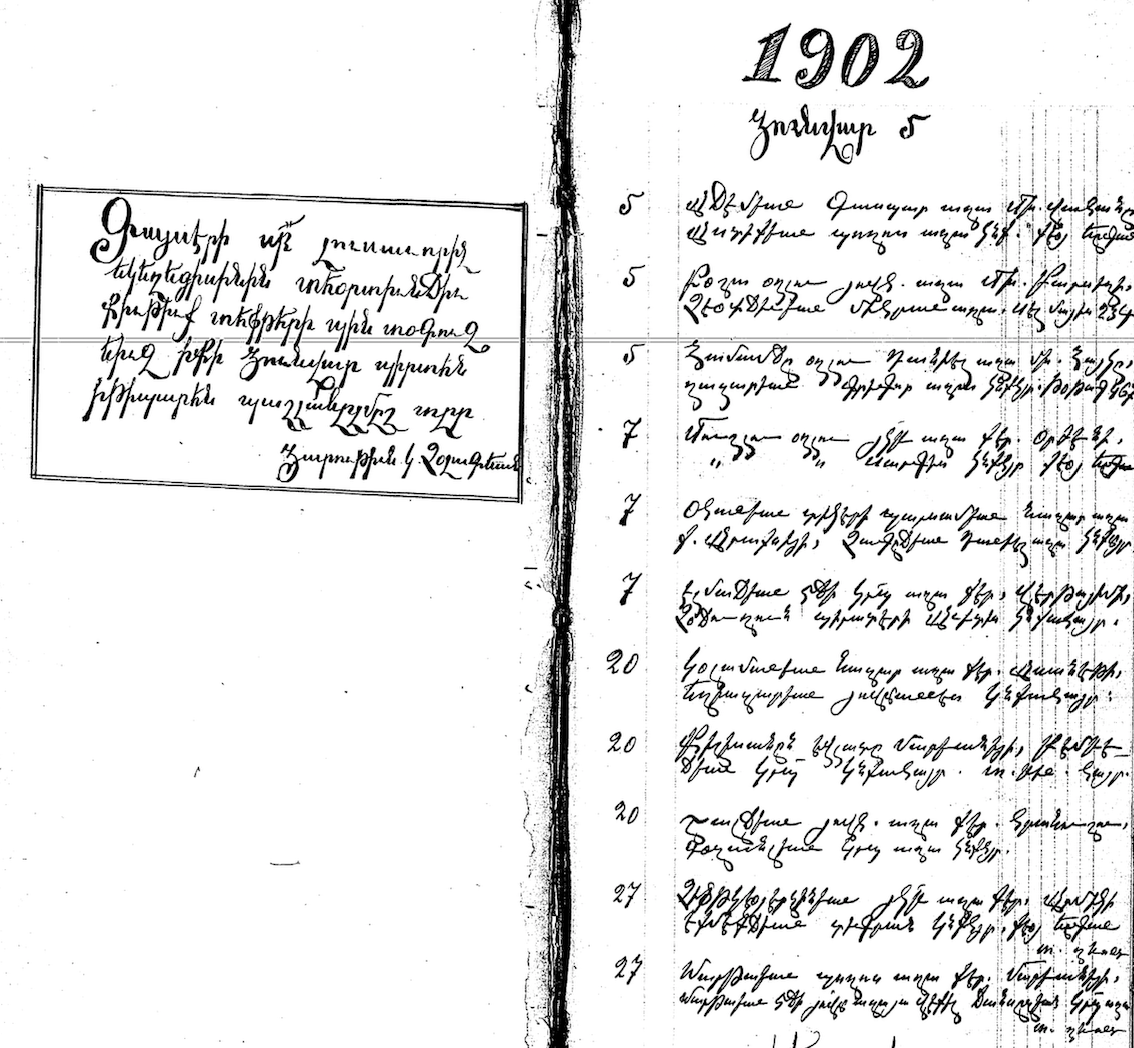

Outside of Istanbul, the baptismal records from St. Krikor Lusavorich church of Gesaria [Kayseri] are available from 1902. There are also limited records from the church in Iskenderun from after the genocide. I have made great use of the Gesaria records in particular, even for periods after the genocide. For example, just this past month I learned of an Aghjayan family that continued to live in our ancestral village until at least the 1940’s. This was previously unknown to my family and has quickly become a new avenue for my personal research.

There are many other interesting items from the Patriarchate of Istanbul that were microfilmed and included in the LDS collection. One example is the “aristocratic contributors to the vartabedner [unmarried priests] of the monasteries of Lim and Gdoutz (1786-1810).” These sorts of records are ripe for more thorough research.

The midwife records from Aintab were already described in part 2 of this series. However, a register of Aintab baptisms from 1818 to 1825 was located in the Catholicosate of Cilicia archives in Antelias by Khatchig Mouradian. Thus, I still retain hope that more such records exist, but have just not come to light yet.

The records of the Armenian Catholic Church are also available. Beyond the Istanbul vicinity, there exist records for St. Terez church of Angora [Ankara] dating to 1830. While records for the Armenian Catholic church of Mardin only exist beginning in 1919. Still, as already noted, the post-Genocide records can also yield important results.

It is worth noting again the important role played by the memorial books for numerous historic Armenian towns and villages. Diaporan institutions also can be an important resource for your research. For example, Project Save’s photographic archives, the previously mentioned Houshamadyan website and the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research (NAASR) all contain interesting resources that can add both a greater understanding of the life of our ancestors as well as specific information on family members. As just one example, similar genealogy wheels like those used in the article on Hazari can be found in the NAASR archives as well as those of the Armenian Museum of America.

One final note, in 2015 I was able to locate a previously unknown part of my family still living in Turkey. The only way to locate these relatives, separated from us through the trauma of the genocide, was through DNA testing. The window of opportunity is rapidly closing to repair the rupture caused by the Genocide and we must make use of all the modern methods available.

Author information

The post Research Your Armenian Roots—What You Need to Know (Part V) appeared first on The Armenian Weekly.

Source: Armenian Weekly

Link: Research Your Armenian Roots—What You Need to Know (Part V)