“Nikol Pashinyan has accomplished more in a month than Serge Sarkisian did in a decade.”

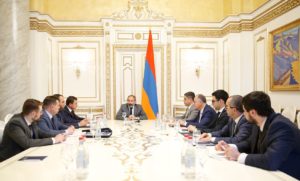

It’s a sentiment that seems to be on everyone’s mind in Armenia’s pink-stoned capital. It refers to the newly inaugurated prime minister’s fulfilment of a long-standing campaign promise to “drain the swamp” (to borrow a phrase from the Americans). One might even be forgiven for thinking that anti-corruption is the only item on the government’s list at the moment, given the lack of coverage on any other initiatives.

Indeed, over the nine weeks since the Velvet Revolution propelled Nikol Pashinyan into the prime minister’s office, investigators have racked up quite a tally. Raids conducted on the notoriously corrupt customs clearance agencies, homes of infamous crime bosses, and murky “foundations” have recovered illegal weapons and tens of millions of dollars worth of embezzled funds for state coffers.

Oligarchs, once-deemed untouchable, now stand by helplessly as state inspectors audit their supermarkets, import-export businesses, and other “philanthropic ventures,” issuing fines with impunity. Draft-dodging charges are being prepared against the sons of well-connected bureaucrats; resignations by prominent officials have turned into a weekly occurrence. No one—it seems—is safe.

Most recently, anti-corruption operations have even been conducted against members of former-President Sarkisian’s own family. His notorious brother and nephew were filmed being dragged out of their home in handcuffs. Even Gagik Tsarukyan, the tycoon-turned-politician who’s Prosperous Armenia party tactically backed Pashinyan’s new government, discovered that he was not beyond reach.

Remarkably, Armenia’s National Security Service (NSS)—the local successor to the old Soviet KGB—is undergoing a complete rehabilitation in the minds of the public. Once associated with the repressive policies of the former regime, the agency’s leading role in these anti-corruption raids has garnered it much praise and jubilation. Its director, Arthur Vanetsyan even reported receiving a flood of job applications over the last month.

Patronage and nepotism have long been decried as some of Armenia’s most pressing issues. Since becoming president in 2008, Serge Sarkisian has repeatedly denounced corruption and cronyism as an “evil, which must be eradicated.” His numerous pledges to introduce “the toughest measures” to tackle corruption have borne negligible success over his decade-long rule. Yet despite the theatrics, assurances, and creation of multiple “anti-corruption task forces,” Armenia’s score has remained virtually unchanged on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index.

Pashinyan’s credentials as a fervent anti-corruption activist (both as a journalist and later as a politician) may explain why he’s so keen on tackling this issue head-on, but there is more to it. The regular releases of new dramatic footage portraying masked NSS officers hauling away nefarious figures à-la-Cops divulge a sense of “security theater” on the part of the authorities.

The media-frenzy over these high-profile anti-graft operations arm Pashinyan with identifiable measures of success to present before the upcoming election.

Fully aware of the jubilant expectations that gained him the premiership, he knows that he must balance sound policy reform—which takes time and offers little visible results for the public—with more palpable evidence that this is no longer “business as usual” in Armenia’s capital. The conspicuous display of once-sacrosanct personalities being slapped by the hand of justice serves this very purpose; a strong indication that no longer is anyone is above the law.

So far, the public seems to have responded positively to these measures. Spirits remain high across the country, as citizens are filled with renewed hope in their country’s future. It should be noted, however, that despite being the most visual way to bring change, anti-corruption raids cannot—on their own—secure the country’s future.

Corruption may seem to be the largest obstacle for development to most, but it’s only incidental. Many countries have undergone impressive periods of sustained growth despite not tackling graft, bribery, and so forth. In these cases, investor confidence supersedes concerns over corruption.

In the months following the bloodless transfer of power, Armenia still finds itself in a precarious situation. For years, the previous government staved off insolvency by borrowing against foreign currencies, causing the country’s debt-to-(nominal) GDP ratio to balloon from 30 percent in 2008 to 92 perecent today. The country still struggles to attract meaningful foreign direct investment (FDI). Last year FDI actually dropped to $246 million (about 80 percent of which came directly from Lydian International, which eco-activists are currently trying to chase out of town). Instability in the wake of the Velvet Revolution has also contributed to a minor economic slowdown; (although the Central Bank still reports robust growth predictions).

Despite upgrading Armenia’s outlook rating to positive, the Singapore-based Moody’s Investor Services warned that protracted instability would erode investor confidence in the country. These concerns may not be at the top of the government’s priority list, as the current focus on electoral code reform may delay any durable decision on economic and fiscal policy until after the parliamentary elections promised for the end of the year.

To its credit, the new government has trodden carefully in retaining many of the policies, which their predecessors polished after years of painful trial and error. They have gone ahead with a controversial (yet extremely necessary) pension reform and pledged to implement the IMF-backed comprehensive reform agenda, which, among other things, would reduce the country’s state budget deficit to 3.3 percent. Improved tax collection methods will help Armenia reach its budgetary goals as well. Pashinyan’s call to the Diaspora for renewed engagement and investment in the country has already been met with success. An official delegation returned from a working visit to the United States and Canada with investment contracts worth $30.5 million in sectors ranging from Information Technology (IT) to hospitality.

Armenian policymakers must counterbalance the risks posed by vulnerability to external shock and residual political instability. To do so, the government must concentrate on cutting bureaucratic red tape wherever possible and reducing government waste.

These actions, as well as comprehensive judicial reforms would boost investor confidence hopefully leading to much-need cash injections into the economy.

Forward-thinking policy-making would prioritize investment in high-productivity and high-value sectors, such as IT and educational infrastructure. The Education Ministry, which has apparently also been swept up by the anti-corruption investigation fever, might soon consider addressing the urgent shortcomings in our education system if our students are expected to become the human capital this country so desperately needs.

These kinds of reforms may not not be sexy—or offer immediate gratification—but they are crucial nonetheless for the establishment of a free, prosperous, and strong Armenia.

Author information

The post Tackling Corruption Is Good, But Judicial Reform and Sound Fiscal Policies Are Better appeared first on The Armenian Weekly.

Source: Armenian Weekly

Link: Tackling Corruption Is Good, But Judicial Reform and Sound Fiscal Policies Are Better