From the Armenian Weekly 2018 Magazine Dedicated to the Centennial of the First Republic of Armenia

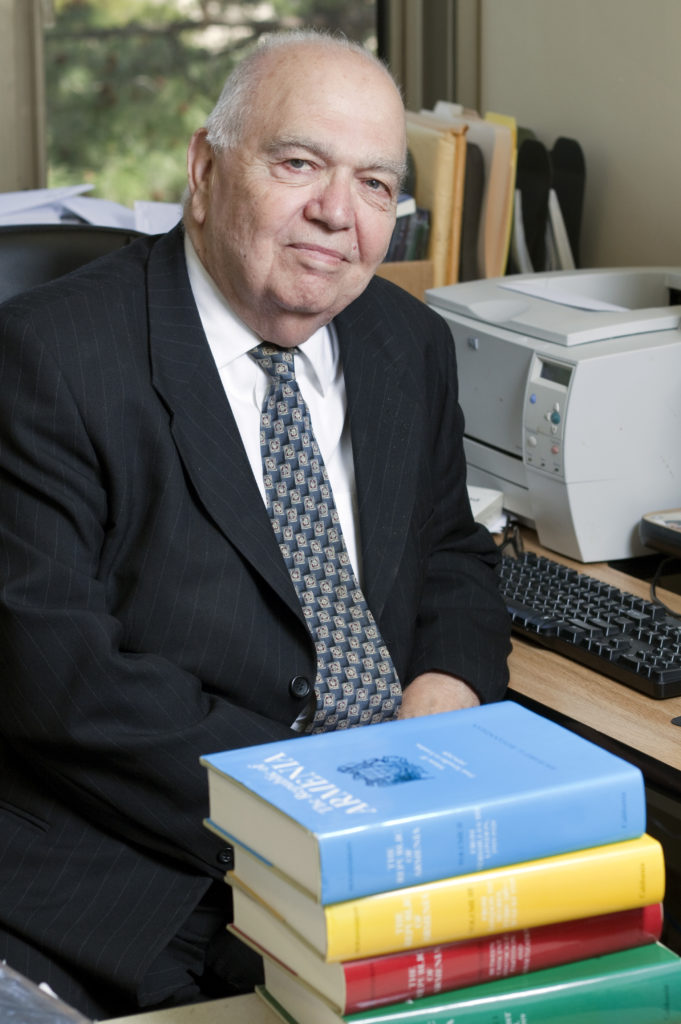

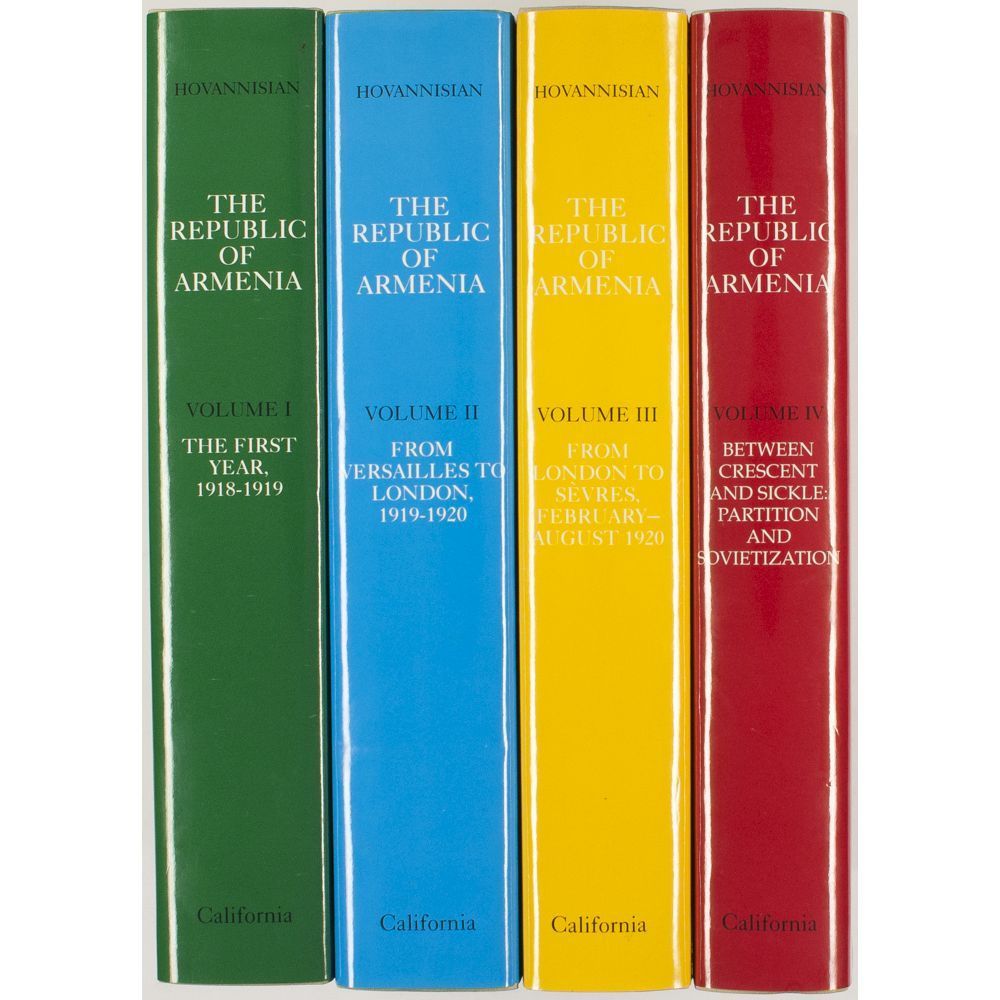

Professor Richard Hovannisian is often asked about the First Armenian Republic. He is, after all, an authority on the subject of the short-lived state. His Armenia on the Road to Independence and four-volume The Republic of Armenia stand as foundational works in the study of modern Armenian history and as exceptional contributions to the field of Armenian Studies.

When queried about the now century-old republic, the professor recalls a statement by His Holiness Catholicos Vazgen I of blessed memory. Even as the pontiff guided the Church during a time of Soviet rule—when the history of the independent Armenian Republic was either ignored or denounced in Soviet Armenia and the USSR—the Vehapar had eloquently summed up the essence of the First Republic: “He said the Armenian Genocide was the crucifixion of the Armenian people… and May 28, 1918, was their resurrection,” the professor explained.

For Catholicos Vazgen, just as Jesus had risen from the dead three days after his crucifixion, the Armenian people found their resurrection from the horrors of genocide three years after the slaughter had begun—when the Armenian people created what Hovannisian calls “a little nucleus of a state near Yerevan, which would become the hope and focal point of the Armenian people who had suffered so much.” That historic episode has stayed with the professor for decades.

In reality, there was little serious scholarship on the First Republic, both within and outside of the Soviet Union—something Hovannisian sought to change with his scholarly work. Today, after more than five decades since the publication of his Armenia on the Road to Independence, and more than four decades since the publication of the first volume of The Republic of Armenia, those five volumes have stood the test of time.

For Hovannisian, back in 1918, the little Armenian state became a turning point in modern Armenian history: “Without its establishment, the Armenian people would not have had a Soviet Armenia,” he explained. “And without Soviet Armenia, we surely would not have the present Republic of Armenia.”

Below is the Armenian Weekly’s interview with Professor Hovannisian, in its entirety.

***

The Armenian Weekly: How do you assess the development of the historiography of the First Republic after more than five decades since the publication of your Armenia on the Road to Independence, and more than four decades since the publication of the first volume of The Republic of Armenia?

Professor Richard Hovannisian: There was, in fact, aside from repetitive and skewed Soviet publications, very little serious scholarship on the Republic. There were valuable memoirs and interpretations of the officials and participants in the former Armenian government or its agencies, but these were almost all written long before I began my research into unexplored archives in Boston, Washington, New York, London, Paris, and beyond. This is perhaps the reason that my five volumes have stood the test of time and remain widely regarded as the most authoritative history of the Republic.

To make them available to the current readership in Armenia, I worked for several years to have the four volumes of the Republic series translated into the reformed Armenian orthography that had been introduced in the Soviet period, and which predominates in the new independent state. It was a real challenge because I had to compare the text word for word with the original to be sure that the translators had caught the spirit and nuances of the words. And it was also a struggle to insist, whenever possible, on the use of Armenian terminology rather than the Russian- and other foreign-language-laced historical language that had come to prevail in Soviet and post-Soviet publications in Armenia.

Fortunately, there is now a generation of younger scholars in Armenia who are paying serious attention to the Republic and exploring areas that were closed to me. In a recent conference on the 100th anniversary of the Republic, sponsored by the Catholicosate of Cilicia in Antelias [Lebanon], a strong delegation from Armenia demonstrated the new and deeper directions in which these scholars are moving.

It is my hope that they will also explore the Russian archives, especially military archives, to reveal and explain the differences between the diplomatic overtures by Soviet Russia toward the Republic of Armenia and the contradictory, aggressive military maneuvers that the Red Army undertook in 1920. And what details are there of the negotiations between the Kemalists and the Soviets during the summer of 1920 just before the Turkish invasion of the Kars province and the disastrous resulting Treaty of Alexandropol? These are just examples of what hopefully will be elucidated.

A.W.: Were Armenian leaders surprised by the fall of Russia in 1917-18 and independence, considering that the Armenian independence arrived on May 28, after Georgia and Azerbaijan?

R.H.: Almost everyone and every ethnic group was surprised by the dizzying course of events in 1917-18. For the Armenians, it was particularly chaotic, as the Russian armies withdrew from the occupied portions of Western Armenia, followed by the Soviet government’s relinquishing to Turkey all of Western Armenia, as well as Kars, Ardahan, and Batum. The Turkish invasion of 1918 threatened to extend the genocidal operations into the heart of Eastern Armenia.

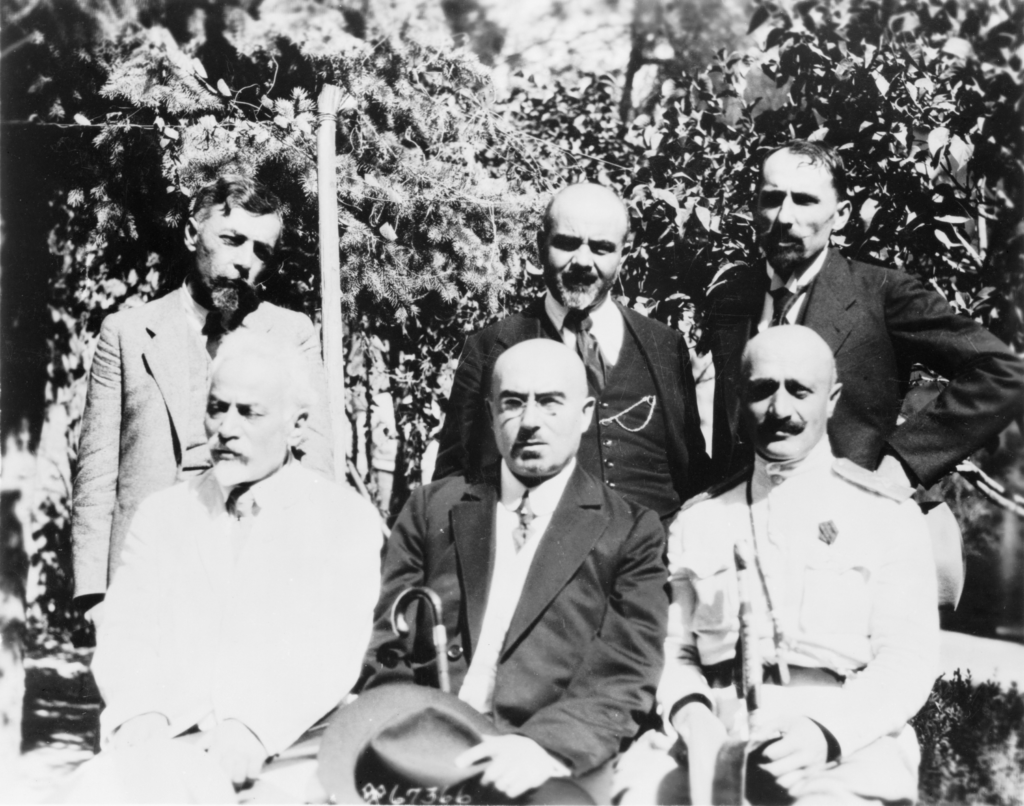

Of course, the Armenians were surprised and bewildered. They were compelled to declare the independence of the little of what was left of their historic lands in the Caucasus after both Georgia and the Muslims (now Azeris) had abandoned them and taken measures to protect their own people. Under these frightful circumstances, the Republic of Armenia was unplanned and unwanted.

The Armenian liberation movement had always been directed toward Western, or Turkish, Armenia, not toward the area around Erevan. But the leaders of the Armenian National Council, located in Tiflis, had no other option but to declare the independence of this rump state, which began with barely 8,000 square kilometers (around 3,000 square miles) but thanks to the defeat of Germany and Turkey was able to quadruple in size by the spring of 1919.

A.W.: Was Armenia’s foreign policy pro-Western or pro-Russian (White Russians)?

R.H.: During the Armenian torment of World War I, the Allied Powers had made many solemn pledges regarding a safe and secure “national future” for the Armenians without the “blasting tyranny of the Turks,” so it was natural that the Armenians would adopt a pro-Western orientation in the fervent hope that a truly independent republic might be formed through the unification of Eastern and Western Armenia, with outlets on the sea.

Ideologically, the leadership of the Armenian Republic was hostile to communism and the Soviet system and, while not comfortable with the White Russians, tried to reach an accommodation with them to relieve pressure on Armenia from Azerbaijan and Georgia and also to safeguard the countless thousands of Armenians living in South Russia and the Crimea under the control of the White Armies. Most observers believed that the Soviet system would not endure.

In hindsight, perhaps the Armenian government should have attempted more serious diplomatic feelers for a modus vivendi. On the other hand, the Georgian example may be instructive in that such an agreement was reached with Soviet Russia, including the exchange of diplomatic missions, but this did not at all deter the Bolsheviks from continuing their subversive activities and the Red Army from ultimately subjecting Georgia to the same fate as Azerbaijan and Armenia.

A.W.: Is the Transcaucasian federalism project adopted by Georgians, Armenians, and Azerbaijanis a good solution for the South Caucasus now?

R.H.: Ideally, federation or confederation could benefit all the constituent states of the Caucasus, but the experiment of the short-lived Transcaucasian Federation in 1918 and the imposed Federation under Soviet rule from 1922 to 1936 demonstrated that the interests of the component parts were not sufficiently cohesive to make such a solution viable.

Hypothetically, it still remains a desirable and advantageous arrangement, but the likeliness is remote, and the opposite processes seem to be at work in the world—as in the cases of Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, Sudan, and the current heated situations in Belgium and Spain. Still, close cooperation among the Caucasian republics would be highly advantageous to all.

They lived and died with the people, and to my knowledge not a single one attempted to enrich himself through a position of privilege or power. It was a highly idealistic, visionary generation, the likes of which may not be seen again.

A.W.: Armenian political life revolved around the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF) in this period. How did the party behave with its rivals?

R.H.: The Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF – Dashnaktsutiun) was the predominant Armenian party in the Caucasus since the early 20th century. It had the possibility and sometimes the necessity of ruling alone, but faced with the overwhelming challenges of 1918-1920 the Dashnaktsutiun was desirous of gaining the cooperation of the other parties, as seen in the composition of the Armenian National Council, which ultimately declared the independence of Armenia, and especially in its subsequent formation of a coalition governments with the liberal Joghovrdakan (Constitutional Democrat or Ramgavar equivalent) party, which was made up of highly educated professionals—lawyers, bankers and financiers, middle class merchants, and intellectuals—with important contacts in the non-socialist world and with the more conservative Western Armenian circles headed by Boghos Nubar Pasha in Paris.

In the spring of 1920, however, the supreme Bureau of the party took full control of the government to suppress an abortive Boshevhik May-Day uprising immediately after the Red Army had marched into Azerbaijan, and, under Ruben Ter-Minassian, then crushed the defiant non-Armenian enclaves south of Erevan. After the brief Armenian-Turkish war of September-December 1920, the Dashnaktsutiun again sought support from a minor party, this time the left-wing Socialist Revolutionaries, who joined the final cabinet that was to deliver what was left of the Armenian Republic to the Soviet order.

A.W.: How might one assess the foreign policy and domestic politics of the Armenian government during these 20 months of independence?

R.H.: In foreign relations, the primary activities revolved around attaining a favorable solution to the Armenian question through convincing the Allied Powers and the United States of America that Armenia’s wellbeing was in their own vital interest. This was not an easy assignment, because Armenia had few resources that would be immediately available to the Western powers, and so the Armenians had to advance primarily moral and humanitarian arguments. Meanwhile, Armenian unofficial and official missions on five continents tried to further Armenia’s cause.

In the end, the Allies discharged their obligation to Armenia in the Treaty of Sèvres by sanctioning the creation of a united Armenian state with the award of parts of the Ottoman provinces of Trebizond, Erzerum, Bitlis, and Van to the already existing “Erevan republic.” But, at the same time, they had already made it clear that they would not provide the requisite military assistance to expel the Turkish armies from these areas. That, the Armenians would have to do themselves. The outcome is well known.

The domestic picture was brighter. Famine conditions had abated, and thousands of orphans had been clothed and housed under the auspices of Near East Relief and Armenian agencies. In 1920, all arable land was seeded for the first time since the beginning of the world war six years earlier. Although there was still much about which to complain, including the heartless extortionist bureaucrats—chinovniks—left over from tsarist times, the edifice of a parliamentary cabinet system of governance had been put in place; popular elections had been organized; agrarian, zemstvo (communal self-governance), and educational reforms had been initiated, including the opening of Armenia’s first university. Armenia’s legal system began the transition to conducting proceedings in the national language, and the country witnessed its first trial by jury.

Hopefully, the current and future leadership of the Republic of Armenia will both embrace the admirable visionary attributes of that past generation and find the road to rational, practical measures to address the many complex challenges that, a hundred years later, have carried over from the original Republic of Armenia.

A.W.: Can the creation of the ephemeral First Republic of Armenia three years after the beginning of the Armenian Genocide be considered a success or a failure, in terms of nation-building?

R.H.: I would term the Republic a “blessing in disguise” or “an unfinished symphony.” It was unable to reach its coveted goal of “Azat, Ankakh, Miatsial Hayastan,” and many of its initiatives remained in their early stages—interrupted by the interlude of the Soviet years. Yet, with all its shortcomings, the Republic had put Armenia on the map and became a symbol for generations in the Diaspora, which preserved the ideal of an independent Armenian homeland. It was not the desired homeland of the Armenian revolutionary movement, and ironically Soviet Armenia was left with only half the territory of the Republic, but it remained a magnet for the Armenian people and the hope of one day realizing their dreams.

A.W.: What are some parallels we can draw between the First Republic and the present Republic of Armenia?

R.H.: There are many parallels, such as being a landlocked, blockaded country, economic dislocation and collapse, continuous tension and sometimes bloodshed along the borders, inability to guarantee all citizens a minimum standard of living, and the complex issue of relations with a vital Diaspora.

But there are also differences. The post-Soviet Republic has endured more than a quarter of a century, it has been admitted into the international community of nations and many agencies, and from the outset it inherited an advanced infrastructure, which was lacking in the First Republic. Yet, while the latter small state began with absolutely no resources, within two years it had started to gradual upward spiral, whereas the current Republic started from a rather elevated position, structurally, economically, and socially, but quickly descended into a dark abyss before starting a slow recovery—unfortunately having already lost a significant part of its population to emigration.

As for the leadership of the First Republic, the ministers may not have been very experienced in governance and perhaps made some questionable decisions, but their absolute dedication leaves no room for doubt. They lived and died with the people, and to my knowledge not a single one attempted to enrich himself through a position of privilege or power. It was a highly idealistic, visionary generation, the likes of which may not be seen again.

Hopefully, the current and future leadership of the Republic of Armenia will both embrace the admirable visionary attributes of that past generation and find the road to rational, practical measures to address the many complex challenges that, a hundred years later, have carried over from the original Republic of Armenia.

Author information

The post The First Republic as Turning Point for the Armenian Nation: A Conversation with Professor Richard G. Hovannisian appeared first on The Armenian Weekly.

Source: Armenian Weekly

Link: The First Republic as Turning Point for the Armenian Nation: A Conversation with Professor Richard G. Hovannisian