From the Armenian Weekly 2018 Magazine Dedicated to the Centennial of the First Republic of Armenia

When I first read about the Second Congress of Western Armenians, held in Yerevan in 1919, I felt pride that two of my ancestors had been key participants. That feeling soon gave way to a need to further explore that historic event.

An analysis of the Congress reveals striking parallels between the attitudes of Western Armenians regarding the “repugnant Russianism” of the First Republic and its inhabitants—and the attitudes of many Western Armenians in the Armenian Diaspora regarding today’s Armenia, a century later.

For the survivors of genocide, who subsequently fell victim to hunger and disease, the newly independent republic of 1918 seemed neither haven nor home. To make the lessons from that nuanced chapter in Armenian history relevant to our world today—to best move forward—we must first look back.

***

Despite the perception of relative liberty in the south Caucasus after the February Revolution in Russia overthrew the Tsar in 1917, the 300,000 Western Armenian refugees who were fleeing genocide could not escape persecution.

From Bayazid, in Russian-held Western Armenia, came complaints that former Romanov officials continued to oppress and disarm the populace while Kurdish violence against Armenians ran rampant.1 Two years earlier, prior to the Russian occupation of portions of Western Armenia, General Yudenich had informed Count Vorontsov-Dashkov of his intent to prevent the Armenian refugees now in the Caucasus from reclaiming their lands in the Alashkert Plain and Bayazid valley, expressing his desire to instead populate the border area with Russians and Cossaks.2

The First Congress of Western Armenians was convened in Yerevan in May 1917, and initiated the creation of an executive body to secure the physical existence of the Western Armenians, revive their disrupted economy, rebuild their homeland, and provide a progressive education for their youth. By the end of 1917, 25 primary schools were in operation in the Van area alone to serve the native population that had streamed homeward. Nearly 150,000 natives of Van, Bitlis, Erzerum, and Trebizond vilayets had repatriated.3

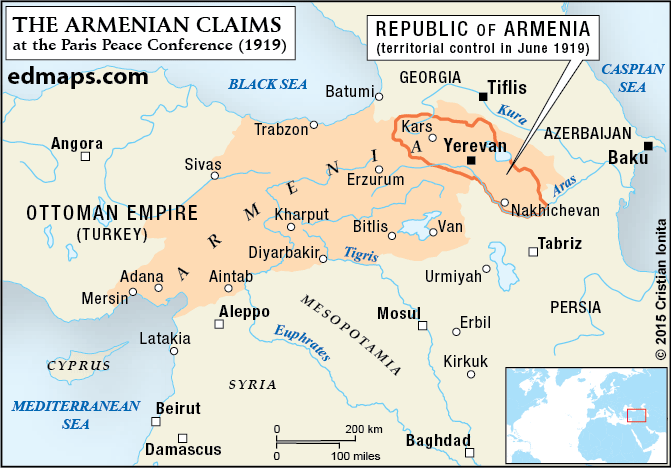

After the October Revolution of 1917, Russian forces withdrew from the Caucasus. Taking advantage of the subsequent vacuum, the Turkish armies of General Vehib Pasha succeeded in occupying Erznga (Erzincan), Papert (Bayburt), Garin (Erzerum), Sarikamish, Kars, and Alexandropol (Gyumri) starting in Jan. 1918. The Turkish advance was finally halted at the battle of Sardarabad, deep into Armenian territory, on May 26, 1918. Consequently, the treaties of Brest-Litovsk and Batumi awarded the Turks nearly 20 percent of the territory of Armenian Republic. Thus unable to harvest crops from the fertile Ararat valley, more than 200,000 among the population of the Armenian Republic perished from hunger and disease in the following months.4

***

Yerevan was merely a provincial town a century ago, yet it formed the nucleus of the infant Armenian republic that emerged after nearly six centuries of foreign rule. Western Armenians would have preferred for that state to re-emerge in the heart of the Armenian Highlands, in Asia Minor. Instead they found themselves refugees in a peripheral province that bore the marks of all things Russian.5 Some half a million Western Armenians impatiently awaited the opportunity to return to their homes; to them, the government and capital of liberated Armenia should have been in Garin, Van, or even a major city in Cilicia, but certainly not, as General Antranig put it, “in the capital of an Armenia carved out by the hand of the Turk.” 6

The political and intellectual leaders of Western Armenians shared such popular misgivings, but they also recognized the potential consequences of lasting internal division.

The Armenian Republic’s government initiated the Second Congress of Western Armenians, which met in Yerevan Feb. 6-13, 1919, to discuss the political goals of the Western Armenians and issues associated with their repatriation. A nine-person elected Executive Body was instructed to implement the decisions of the Congress and to function until the creation of a combined government of United Armenia.7

Two of my ancestors, both from Bayazid, were members of that Executive Body: Vahakn Kermoyan, a Lausanne-educated lawyer and writer, was an influential member of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF);8 Arsen Gidour, a graduate of the Kevorkian Jemaran (Seminary) in Etchmiadzin, was a member of the Hnchakian party and a veteran of the Battle of Sardarabad.9

The Western Armenian leaders placed their aspirations in the hands of the Armenian National Delegation to the Paris Peace Conference, led by Boghos Nubar Pasha, an influential politician and the former chairperson of the Armenian National Assembly of the Ottoman Empire. Although ARF members and sympathizers formed the majority of the Second Congress, they regarded Boghos Nubar as the person best qualified to advance Armenian interests at the Peace Conference.10

The Congress’s Executive Body communicated its demands to Paris: Armenia’s right to statehood, the liberation of Western Armenia in order to constitute a United Armenia, and punishment for the architects of the systematic massacre of the Armenians.

A new National Delegation was named in April and included the famed ARF revolutionary Karekin Pastermadjian (Armen Garo), respected in both Western and Eastern Armenian circles, with the hope that his history of collaboration with Boghos Nubar would create a more unified front during negotiations.11

On May 28, 1919, in Yerevan, on the anniversary of independence, Prime Minister Alexander Khatisian read the adopted text of The Act of United Armenia and invited the 12 newly designated Western Armenian deputies to sit alongside members of the Republic’s Parliament. Speaking on behalf of those 12 parliamentarians, Vahakn Kermoyan pledged active Western Armenian participation in the Republic to work toward the goal of a united, independent Armenia.12 Despite having no jurisdiction beyond the Republic’s borders, Yerevan festively celebrated the declaration of Armenian unification.

***

Nearly a century later, we again have an independent Republic—despite the Turkish crescent and the Russian sickle. Yet, the unfortunate reality remains that Armenians are dispersed across the globe, and more of us reside outside of our homeland than within it.

Recently, however, many Western Armenians have sought refuge in Armenia to escape war in the Middle East, and some others from the Diaspora have also “repatriated” and are playing a role in the country’s revitalization. The issues prevalent a century ago continue to be discussed among this new generation of Diasporans returning to Armenia.

No Armenian is immune to foreign influence, whether in Armenia or in the diaspora. To overcome the obstacles of dialect, custom, tribalism, and mistrust, both the government and its citizens must collaborate to foster an environment of inclusivity, encourage and provide incentive for repatriation, and denounce all types of discrimination.

And perhaps such measures might include following the example of the First Republic by having active Western Armenian participation in all strata of government to bridge our artificial divisions.

Notes

- Hovannisian, R.G., Armenia on the Road to Independence, 1918; University of California Press, 1967, pp 77-78

- Ibid., 57-58

- Ibid., 78-79

- Ibid., 210-211

- Hovannisian, R.G., The Republic of Armenia, Vol. I; University of California press, 1971, pp 450

- Vratzian, S., Hayastani Hanrapetutiun [Republic of Armenia] 2nd ed.; 1958, pp 256

- Hovannisian, The Republic of Armenia, pp 454

- Tarbassian, H.A., Erzurum (Garin): Its Armenian History and Traditions; Garin Compatriotic Union of the United States, 1975, pp 222

- Kitur (Gidour), A. Patmutiun S. D. Hnchakian Kusaktsutian, 1887-1963 [History of the S. D. Hnchakian Party, 1887-1962] Vol 1; Beirut, 1962, pp 480

- Hovannisian, The Republic of Armenia, pp 453

- Ibid., 458-459

- Vratzian, Hanrapetutiun, pp 264

Author information

The post The Lasting Legacy of the Second Congress of Western Armenians appeared first on The Armenian Weekly.

Source: Armenian Weekly

Link: The Lasting Legacy of the Second Congress of Western Armenians