An Interview with ‘They Shall Not Perish’ Executive Producer Shant Mardirossian

WATERTOWN, Mass. (A.W.)—During the Armenian Genocide, the plight of the Armenian people was making headlines throughout the United States. Thousands of miles away from the treacherous deserts of the Ottoman Empire, ordinary Americans were organizing fundraising efforts and raising unprecedented amounts through various aid programs to help save the Armenians.

“They Shall Not Perish” will be making its Boston public premiere on Oct. 13, at the Scottish Rite Masonic Museum, in Lexington, Mass.

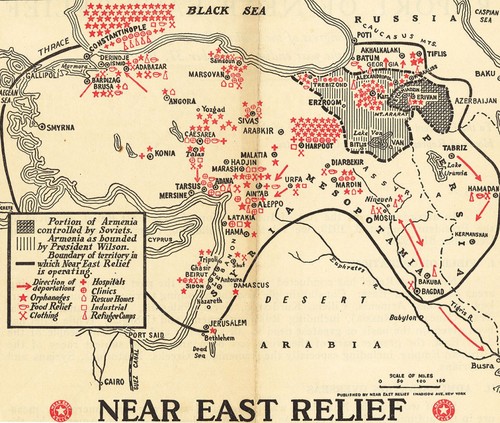

The response of the Near East Relief (NER) to reports of “race extermination” against the Armenians, Assyrians, Greeks, and other Christian minorities of the Ottoman Empire is considered to be the United States’ first collective display of overseas humanitarian aid. In 15 years, NER would raise more than $116 million and mobilize hundreds of volunteers to help the effort.

More than a century after the organization’s establishment, Near East Foundation (NEF, the successor organization of NER) Board Chairman Emeritus Shant Mardirossian decided that the somewhat-forgotten story of the NER—an intrinsically American story, he says—should be told to a wider audience.

That is when Mardirossian commissioned and produced a documentary, written and directed by George Billard, called “They Shall Not Perish.”

They Shall Not Perish: The Story of Near East Relief – Preview from George Billard on Vimeo.

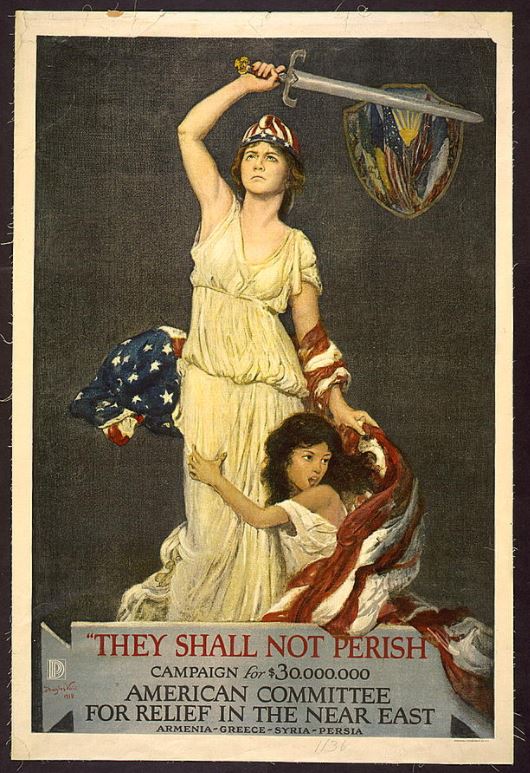

“I named the film ‘They Shall Not Perish’ after one of the famous [NER fundraising] posters, which shows Lady Liberty standing with a sword and a young orphan by her ankles wrapped around the American flag,” Mardirossian told the Armenian Weekly’s Rupen Janbazian in a recent interview, ahead of the film’s Boston premiere. “That just shows, symbolically, how committed Americans were to the effort.”

Mardirossian said his number-one priority is to get as many people to watch the film and learn about the Armenian Genocide and about the mass relief effort. He is in the process of finalizing a deal with on-demand video giant Netflix to have the documentary available to all subscribers starting next year, and he is helping to include the story of NER in high school Armenian Genocide curricula.

The film will be making its Boston public premiere on Oct. 13, at the Scottish Rite Masonic Museum, in Lexington, Mass. Below is the interview with Shant Mardirossian in its entirety.

***

Rupen Janbazian.: You have said that you would like to shed light on an important chapter of American history through this film. What makes the story of Near East Relief (NER) an important part of U.S. history?

Shant Mardirossian: The story of NER is an important part of American history, which identified the beginning of international humanitarianism led by the U.S. This was the first major effort on the part of American citizens, who really organized a massive fundraising campaign and logistics effort that led to the rescuing of 132,000 orphans, the saving of more than a million refugees—not just Armenians, but also Assyrians, Greeks, and other minorities that were being affected.

It was really the beginning of a national movement, and today it’s so common—we have organizations like USAID (United States Agency for International Development) or UNHCR (The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees). Before this organization—before NER—these type of organizations did not exist. They only came into being later, in the ’30s and ’40s.

NER was really a model for what international humanitarianism should look like. So, I think it’s important that it’s taught in American public schools and that it becomes part of American history. It’s very relevant.

R.J.: It’s been said that NER’s use of mass media was a first for a philanthropic organization. It’s interesting now that a film has been made about the effort and the medium is being used to tell the story of an organization that pioneered the use of film and other media.

S.M.: They clearly were pioneers in the way that they used mass media to mobilize a grassroots effort. For example, film was just being introduced to the masses—silent film.

In 1919, in order to raise awareness about the atrocities that were taking place against the Armenian people, NER commissioned the film “Ravished Armenia,” which, as you know, is the story of Aurora Mardiganian. The organization also helped Aurora get to the U.S. after she had been enslaved, raped, and seen most of her family massacred. She escaped from the harem that she was in and eventually made her way to NER workers, who helped her get to the U.S. When they brought her to the U.S., they helped write her memoir and commissioned a film around it. The film went on to become a box office success, and it toured around the country for a 30 million dollar campaign in order to raise awareness and to raise funds for the efforts. This had a tremendous impact.

And ad for “Ravished Armenia,” also known as “Auction of Souls,” in the Times-Republican of Marshalltown, Iowa

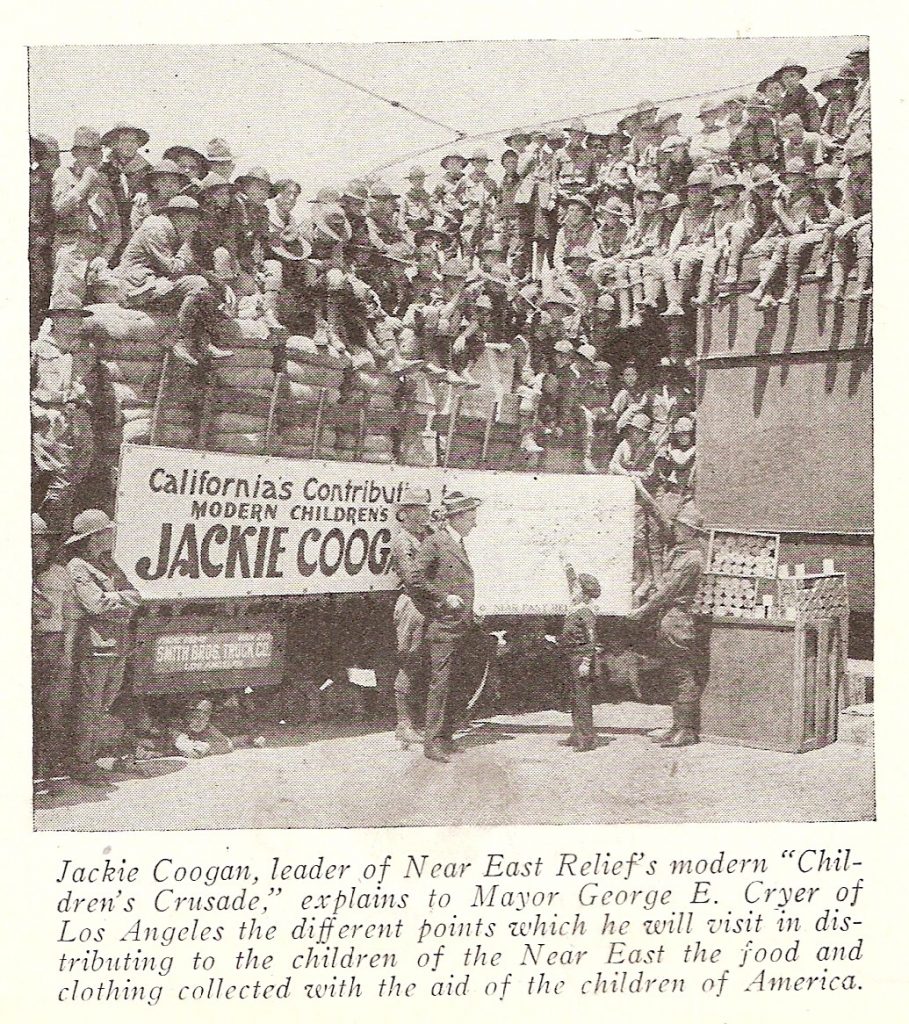

Subsequently, after that, NER used the first celebrity spokesperson Jackie Coogan—the child actor who appeared in Charlie Chaplin’s films. He portrayed an orphan, so what better actor to use to save the orphans. He was a success known around the country, so they enlisted him to promote the film and to go around the country and raise money and collect clothing. He even escorted a ship to Athens, where they delivered, firsthand, humanitarian aid—clothing, food, supplies, etc.

(Below: A restored, 24-minute segment of “Ravished Armenia” was produced by the Armenian Genocide Resource Center of Northern California – https://archive.org/details/RavishedArmenia1919)

[archiveorg id=RavishedArmenia1919 width=640 height=480]

Today, we are so accustomed to celebrity spokespersons—form George Clooney to Angelina Jolie. This was the beginning of that. A hundred years ago, this kid was the George Clooney of his time.

R.J.: The NER campaign was also well known for its beautifully designed posters to raise funds for the Armenians and other minorities. Tell us more about that.

S.M.: NER hired the best graphic artists at the time to develop posters for the campaigns. The posters were used as a way to touch on emotions: They were usually of women and children refuges under the protection of something symbolic of an American.

Patriotic posters were made to appeal to Americans appreciation of their own freedom; this poster, which inspired the name of film, was designed by Douglas Volk 1918 (Photo: Near East Foundation)

I named the film “They Shall Not Perish” after one of the famous posters, which shows Lady Liberty standing with a sword and a young orphan by her ankles wrapped around the American flag. That just shows, symbolically, how committed Americans were to the effort. Americans saw themselves as a protector. They saw the Armenians as a persecuted Christian minority; they identified with them because, since the 1800s, there was a real connection there through the missionaries who were there—there was a lot of news and discussion about Armenians. Moreover, many Armenians were going back and forth from the U.S. and were participating in communal affairs, literature, politics.

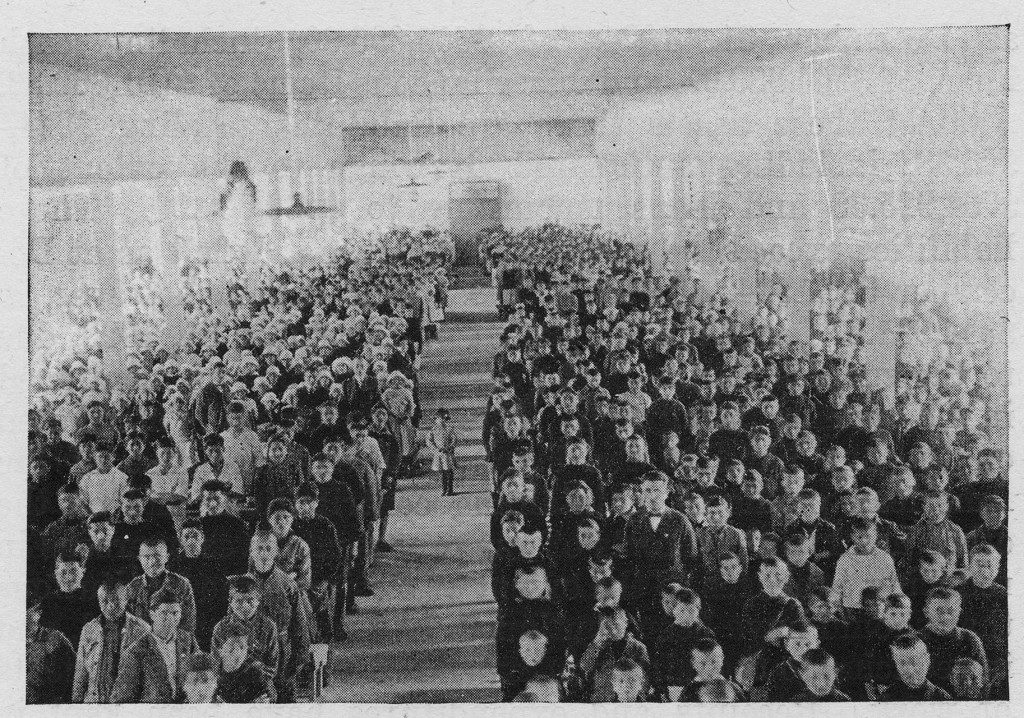

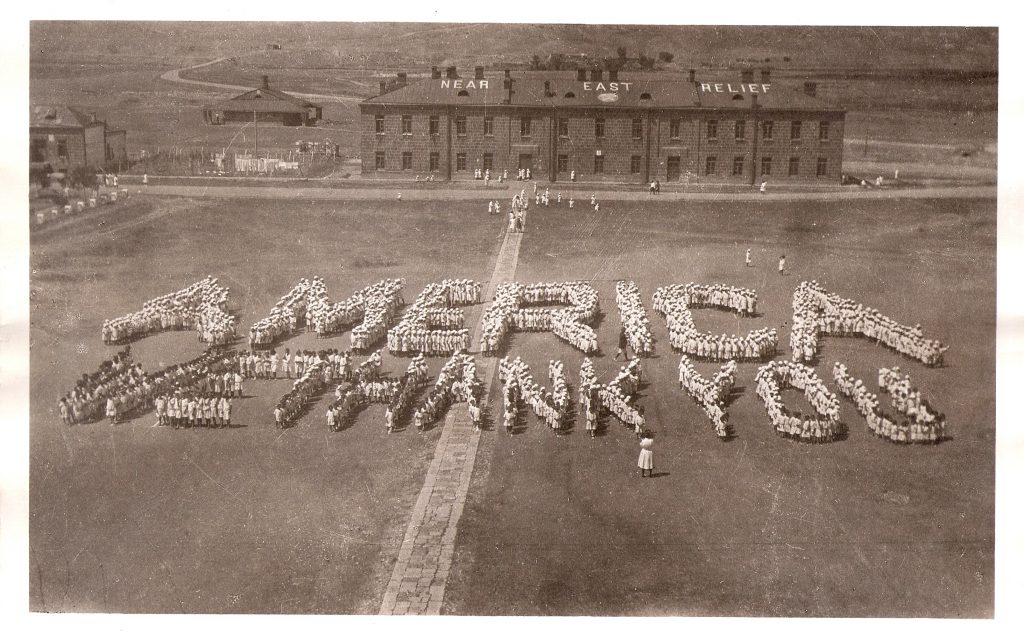

2,500 orphans at Near East Relief Alexandropol spell out “America We Thank You” (Photo: Near East Foundation)

So, there was an awareness of who the Armenians were and Americans felt like there was a real connection with them. They saw them as brethren in the East.

R.J.: Was this largely due to a shared religion?

S.M.: It’s clear that there was an affinity for the Armenian because of the common religious connection. There is no question. The Protestant missionaries had—over a hundred years before that—been in the Ottoman Empire and largely served the Armenian community and had helped establish a Protestant Armenian community there. They were also enlightening them to a certain extent. They were bringing in Western education, Western political ideas, Western ideas of equality, and all of these had an impact on the Armenian population. They were going through persecution during the late 1800s and identifying with these ideas, which were American and European. Armenians were agitating for equal rights: Can a Christian be an equal of a Muslim in the Ottoman Empire? That was the question that was being asked. They did not have equal rights, they did not have equal protection, so they were seeking that.

It’s ironic, because similar issues were occurring in the U.S. at the time. This is when the suffrage movement was being fought for. This was also not that far after the Civil War had ended, at a time when the issues of segregation, civil rights, and all of these things were being dealt with. It’s ironic that the missionaries felt that way about the Armenians overseas and did not necessarily believe that those same issues were happening in their own country and weren’t necessarily dealing with it.

It’s an interesting period around the world. The U.S. was only beginning to emerge as a superpower. When WWI broke out, the U.S. tried to stay out of it, as long as it could, until it was finally dragged in on the European front. It chose not to enter the war on the Ottoman front, interestingly enough. It felt like it could potentially protect its own assets there. There was a selfish aspect to it, which is mentioned in the film. At the same time, if the U.S. had entered the war, it would have lost its ability to protect and provide humanitarian assistance to the Armenians. So there was this kind of hypocritical stance that the U.S. had to take, in a sense, not to intervene militarily, but to intervene from a humanitarian standpoint. Could that have prevented the Genocide? Could it have “lessened” the Genocide? No one knows for sure. But had it not been for the humanitarian efforts, hundreds of thousands more Armenians and other minorities would have perished.

Let’s not forget, this was not a governmental action. These were ordinary citizens who had day jobs. They organized, raised an enormous amount of funds, and even risked their lives to go over there and to provide aid and care. Many doctors, nurses, and other professionals volunteered to go during the Genocide and helped in the rebuilding and re-establishing process. The orphaned children had no skills and no parents. They needed help to learn to read and write, to learn how to organize themselves as a community again, to learn a trade and skill. These volunteers often acted as their parents.

My own grandmother from my father’s side and all of her siblings, who were left orphaned, relied on American orphanages to help them survive for four years. They learned how to read and write, they preserved their religion and culture, and they were able to learn skills that they could make a livelihood with when they matured. Had it not been for these efforts, they would have likely perished.

R.J.: You’ve mentioned in the past that in making this film you were inspired by the story of your grandaprents’ survival. Tell me a little about your connection to NER and the Near East Foundation and why you chose to tell this story.

S.M.: It was somewhat by coincidence. A partner at the firm at which I worked, Geoffrey Thompson, was the grandson of Barclay Acheson—the first operations director of NER. When we met, Jeff told me he was the chairman of an organization called the Near East Foundation, and that there was a historical connection to Armenians; he had noticed I had an Armenian name.

Barclay Acheson with girls Babek and Lea at the Seversky Girls’ Camp, c. 1925 (Photo: Near East Releief)

We spoke about it, and I had no idea about the organization and the work it had done. He invited me to some board meetings and asked if I wanted to get involved. Of course, NEF was doing development work in the Middle East, and given that my family—including myself—had emigrated from the Middle East, I always had a connection and interest in those countries and wanted to help.

So when I learned more about the history, I discovered this story, which I knew very little about. Frankly, I knew my grandmother had been rescued by orphanages, and Americans had come to help them, but I did not know the background of the story around it. I learned about the organization’s archives that were stored in warehouses in Brooklyn and Manhattan. I learned that they were all deteriorating and the board was trying to figure out what to do with them. I was shocked. I couldn’t believe that these materials and thousands of photographs of orphans in orphanages in Alexandropol [Gyumri], Jerusalem, Lebanon, Syria, and all these places were sitting there, and nobody in our community knew about it.

Birds’ Nest (Lebanon) children playing on carts made by older boys at Mamelstein Orphanage (Photo: Near East Foundation)

Along with another Armenian on the board, we organized an effort to get all of those materials out of the warehouses and put into the Rockefeller Archive Center so that they could be properly curated and people could start researching it.

We organized an exhibit in 2003 for the first time, where we showcased some of these photographs, and at that point it became an obsession for me. I started doing more and more research about it, finding out that there was more of these photographs and materials hidden in other archives and pretty much forgotten.

At the same time, others were also discovering this. Many people were writing books and papers about it, and I got involved with a community of independent searchers and scholars who were working on this subject. However, we were only able to speak to our own community. We were going around speaking to churches, Armenian organization events, when I said to myself, “This is an American story, and we need to tell the American public about it.” Of course, the Armenian audience is important—we should all know about it—but this is an important part of American history that has pretty much been forgotten.

A group of boys from Antilyas Orphanage attend lessons on the beach c. 1925 (Photo: Near East Foundation)

During the campaign for the Centennial of the Armenian Genocide, we decided to create a traveling exhibit, which was shown around the country. We also created a website—a virtual museum—and started putting up these stories and catalogues of photographs.

I had also been working on a film so that we could get this story on public television and in schools around the country. This is a decade-long effort, which ultimately led to the completion of this film. It officially premiered in the April of 2017 at the Times Center in New York and has been on public television across the country—over 40 times at this point.

R.J.: Are there plans for wider distribution? On-demand services, for example?

S.M.: We are currently finalizing an agreement with Netflix, which will have it be available to Netflix customers starting Jan. 2018. We’ve also partnered with Facing History and Ourselves, an organization that promotes the teaching and education of the Holocaust, the Armenian Genocide, and other dark chapters of history that need to be taught. They will be using the film as a part of their revised Armenian Genocide curriculum.

A doctor and nurses conduct medical examinations in an orphanage hall; some children received daily medical care, depending upon their health conditions (Photo: Near East Foundation)

R.J.: And the film will have its Boston public premiere on Oct. 13.

S.M.: Yes. The NEF has been a longtime partner of NAASR (The National Association for Armenian Studies and Research), with which we have collaborated to premiere this film to the Boston audience. We held a sneak-peek showing to a smaller audience in Boston back in March, and there was so much interest and demand that we promised everyone that we would have a public premiere as well.

An image of the Armenian Orphan Rug, 11’7″ x 18’5″, and composed of 4,404,206 individual knots. It took the Armenian girls in the Ghazir Orphanage of the Near East Relief 10 months to weave. The White House displayed the rug in 2014. (Photo Near East Foundation)

R.J.: What’s it like working with an organization like NAASR? Did it have any input in the film itself?

S.M.: It’s really an honor to be working with an organization like NAASR that has done so much for the preservation and research on Armenian Studies and Armenian Genocide-related work. Before we launched the film, the people at NAASR saw it and helped me verify some of the historical facts and descriptions used.

Knights of Columbus of Rochester, N.Y., collect a “mountain of clothes” for Near East Relief in 1923 (Photo: Near East Foundation)

R.J.: How is the NER story still relevant today?

S.M.: Although this story is about the Armenian Genocide and the relief efforts that took place, it is also a universal story. It’s also a reminder of what America once was and what it can be [again]. Today, we are all struggling with some of these issues—particularly how we deal with the Syrian refugee crisis, or the Iraqi refugee crisis. I’m pleased that at least the NEF is doing its share and is involved in helping refugees in Lebanon, Jordan, and now in Syria as well. We’re doing our part, I just wished the American government was doing more. Though a lot of NEF’s funding is coming from the American government, it can still do more.

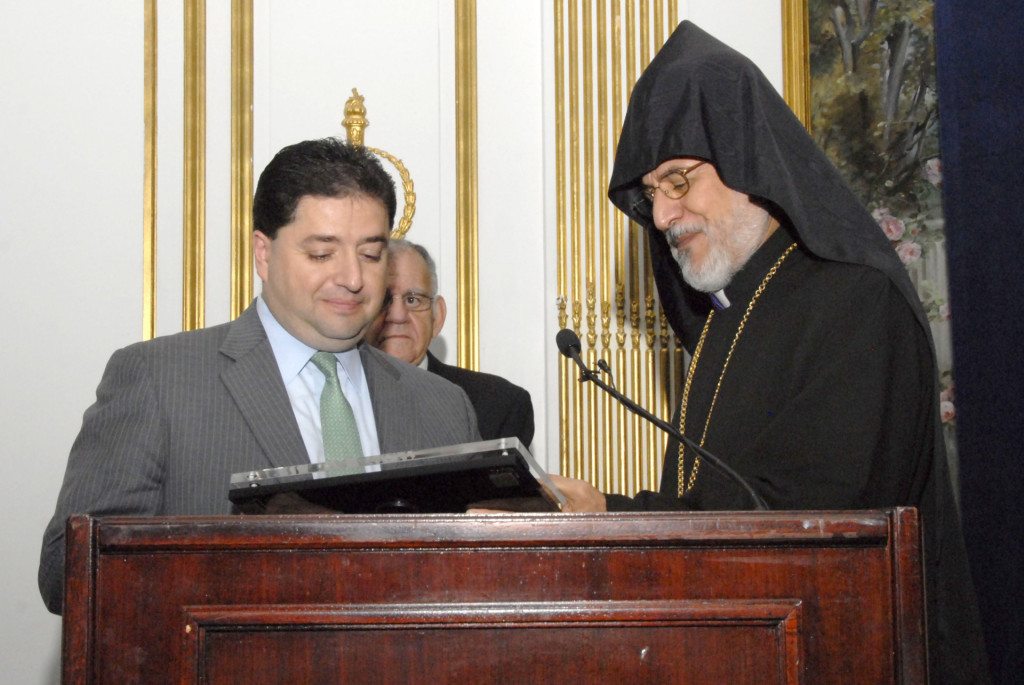

Executive Producer Shant Mardirossian (L) (then chairman of the Near East Foundation) accepts an award from Archbishop Oshagan Choloyan (R), on behalf of Near East Relief. The award was given by the Eastern Prelacy of the Armenian Apostolic Church of America, in 2012. (Photo by Zenop Pomakian)

Hopefully this is just the beginning for the film and its distribution around the country. Public television, Netflix, and Facing History should allow us to reach a much broader audience than just the Armenian community. I hope that others in the community will help us with this effort—whether it’s public television, or public school education—in getting this important story out.

***

The Boston public premiere of “They Shall Not Perish” will take place at the Scottish Rite Masonic Museum, on Oct. 13, at 7:30 p.m. A post-film discussion will feature NEF Board Director and “They Shall Not Perish” Executive Producer Shant Mardirossian and a panel of scholars. The program is free and open to the public, and will be followed by a reception.

The Scottish Rite Masonic Museum (formerly National Heritage Museum) is located at 33 Marrett Road, in Lexington, Mass., at the intersection of Route 2A and Massachusetts Avenue. For additional information about this event, please contact NAASR at 617-489-1610 or hq@naasr.org.

The post ‘They Shall Not Perish’: Telling the Story of Near East Relief through Film appeared first on The Armenian Weekly.

Source: Armenian Weekly

Link: ‘They Shall Not Perish’: Telling the Story of Near East Relief through Film