From Persecution in Baku to Opportunity in the United States

Special for the Armenian Weekly

“I thank God every day for saving us.”

My father speaks these words occasionally whenever we discuss anything remotely related to our arrival to United States on Jan. 31, 1992. Not an extremely religious man, he puts his head up, his face grimaced in disbelief over this small chance for life, or for an opportunity to escape a life of desolation. “Can you just imagine how we would have lived, had this country rejected us.” It’s never a question; it’s a statement, followed by a brief silence and then a cheerful continuation of the conversation about present things or the future.

Our first photo in the U.S., Fargo airport around midnight on Feb. 1, 1992, after 48 hours of travel. Norik (far right), Irina and Anna (fifth and sixth from right), and little Mikhail crying with his back to the photo.

This year, as every year, my parents will receive flowers from me on this deeply personal, intensely emotional occasion, the 25th anniversary in United States—it is my simple way of thanking them for risking everything, and sacrificing everything, to give us the best chance at life. I was almost fourteen and my brother was seven. Along with our parents, four suitcases (only two of which arrived), $180 (USD), and with no language skills, nor a single friend we knew in this country, we arrived and we never looked back.

Many have heard the story. Many lived the story. But today, on this anniversary, I want my parents, Norik and Irina Astvatsaturov, to know that I thank them every day for savings us.

My brother was thankfully too young to know or understand the gravity of the giant step they took to relocate us. As a teenager, I carried this heavy burden of living with the memories my parents tried to guard us against. We escaped the atrocities against Armenians in Baku, and the hungry and dark blockaded Yerevan between 1989 and 1992.

We were given the green light to come to the U.S. two and a half years after becoming refugees, when my father was 44 and my mother 38. Throughout these events that shaped us, I was a quiet and shell-shocked girl who watched them with a curious eye. I was privy to the details of what happened, but it is hard to understand just how we got to where we are today. As a 38-year-old mother of two, it’s now unimaginable to me the sheer depth of the sacrifices and suffering her and my father accepted for the well-being of their children. It is also impossible to imagine the amount of strength it took them not only to make it out alive through the atrocities of Baku, but the ingenuity to survive in Yerevan as refugees along with the drive to succeed and propel their children and grandchildren forward in United States.

After receiving refugee status and being allowed to enter the United States, my family was sent to settle in Wahpeton, North Dakota, where a Methodist Church sponsored us through Lutheran Social Services. The town of Wahpeton is home to about 10,000 and located about 60 miles south of Fargo. It was nothing like what we imagined the United States to be or what we were used to, growing up and living in big cities such as Baku, Yerevan, and Moscow. We were the second family of refugees to the town and one of the first few refugees in nearly a century. Once we arrived, we were brought to live in subsidized housing. After filling out some paperwork with the help of the volunteers and translators, we began receiving food-stamps designated to refugees for the first six months in United States.

The first time we entered our third-floor apartment at 2 a.m. in the morning on Feb. 1, 1992, my father said it was like entering heaven. There was carpeting on the floor, a clean white bathroom with a shower and warm water, a small kitchen and heat. Electricity and heat! We hadn’t had either in Yerevan for many months. There was a glass bowl of bright yellow butterscotch candies on the table; my parents still keep that bowl (albeit disliking butterscotch candies) 25 years later as a symbol of where we came from and the little gestures of kindness from strangers that owed us nothing. There was a small wooden pendulum clock on the popcorn-textured wall. The clock, like everything else in the apartment, was donated and looked out of place in the bright small living room area. My parents still have this clock in their kitchen as a reminder of what a little time and a lot of work can accomplish.

That first time in our new apartment seems so distant now, but still so very real. We asked the volunteers about a curious little box of fluffy paper in the living room. They explained to us that Americans don’t use handkerchiefs but use Kleenex tissue instead. We thought it was funny. They showed us the full fridge and kitchen cabinets and we were so thankful, but were also bemused that the bread was pre-sliced and in plastic bags. After examining the rooms in awe—the shelves of donated school supplies, the full fridge and the warm and bright apartment we could call our own—my family felt relief for the first time in many years.

I was too tired to cry but we hugged and went to sleep after the first hot shower in many, many days. The next day the volunteers took us to the grocery store even though our refrigerator was full. We didn’t buy anything but walked around the store. A few years later I learned that it was a recommendation for the sponsors to any incoming refugees; a psychological band-aid of sorts. Seeing perfectly stacked, polished red and yellow apples, and rows and rows of thoroughly-packaged food in a clean and quiet environment was an unbelievable experience after spending the last four years scavenging for food in empty Soviet stores. Especially after hunting for firewood, or standing in unending lines for six hours for a dozen eggs or a single loaf of bread. The strategy apparently was obviously well thought out because my first diary entry in the United States was about food. The entry first describes the fact that my mother went to the grocery store to get us the food eleven days after arrival. I speak in detail that she spent 75 food-stamp dollars, and we received $409 a month for the next six months.

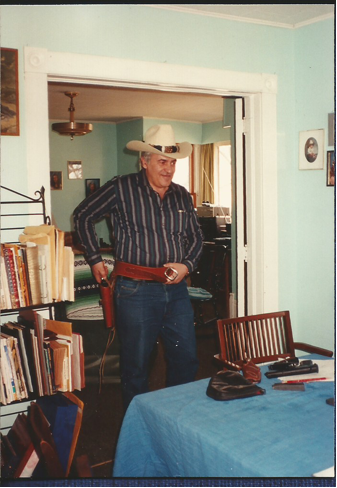

Norik (back left) and Irina (back) right with Evergreen Methodist Church volunteers in Wahpeton, N.D.

The first weeks in the U.S. were surreal to us, to say the least. We were driven to doctor appointments, English classes, and church by church volunteers. Many of them did not understand for years, and some of them will never understand, precisely what we endured and why we came here, but all of the volunteers in this tiny town in the middle of a desolate North Dakota donated their time and their patience to us out of the Christian call to help those in need.

Almost immediately after jet lag wore off, my parents began learning the language—not an easy task; my mother was my age, my father seven years older. Neither of them knew any English at all. In school back in Baku, my father studied a few years of German and my mother a few years of English. It was not enough. They began inviting volunteers over for dinners they paid for with food-stamps, just to get the conversation with English speakers. Despite studying English since the second grade in specialized English school, I had a hard time translating for my parents. Americans spoke so fast; I knew theory, but had no practice speaking or listening to the language. Finding work was impossible for my parents at first. No one would hire them without basic English skills. I remember waking up in the middle of the night finding my father huddled over the English dictionary, writing out English words in his quirky Russian cursive. He did this daily, starting hours before dawn and continuing throughout most of the day. The mere shock of relocation didn’t shake my parents’ determination to work and make life as they saw fit for their children.

During these first months, we faced some interesting misconceptions of who we were. The fabric of our determination was tested. Most people we encountered didn’t know where Armenia or Azerbaijan were located, let alone that Armenians were Christian, or that it was a part of the Soviet Union, and hence modern and industrialized. People were continually surprised at my parents’ education and knowledge, stumped by their broken English and rough and foreign exterior of a newly arrived refugee. We could tell by the reception which members of the Methodist Church actually agreed to the sponsorship and which didn’t. That delineation was also clear decades later. Many people didn’t understand who we were and what the sponsorship meant, especially that we didn’t receive any of the Church’s funds, just their time and volunteerism. Even a few years after arriving, when we scraped and saved every penny to buy our first little home, there was a misconception that somehow we got a better rate or cheaper home because we were refugees or someone gave us extra money. One day in church a man shook my father’s hand and sneaked a five dollar bill into the palm of his hand. My father, thankful yet proud and troubled, looked down at the money in his rough and giant hand and said in his broken English, “Don’t give money, give work.”

No work came until about six months later when my father was hired at a wood processing factory working the night shift, basically 3 p.m. to 3 a.m. We never really saw him after that. He was either sleeping or working. We didn’t own a car and with no public transportation in this rural North Dakota town, my father walked miles in the dead of winter of North Dakota, with -20 to -30 Fahrenheit being the norm.

Work was a God-sent development as the food stamps we received as refugees ran out around the same time. My father worked in this factory until the day of his retirement twenty-three years later. It was a grueling job in the dead of winter and even worse in the over 100-degree heat of the summer. At that same time, my mother began working odd jobs around town, shops, garden nurseries, ironing clothes for several locals, and then few years later in the high school cafeteria. During my senior year of high school, she began teaching art around the state as an Artist in Residence, a state program to expose high school students to alternative art mediums. During those first years when my brother was little she was able to be home part of the day when we arrived home. After school, we attended English classes taught by a fellow refugee who was barely fluent in English. At that time, there were no specialized ELL programs or materials. When we got home, my brother often cried about his difficult days in First Grade where kids teased and sometimes hurt him for not speaking the language. The school was not equipped to deal with the non-English speakers and when my brother began exhibiting stress and anger in school, the school administration cited our socio-economic status. With their broken English, my parents were able to retort that their daughter’s successes in school were the fruits of that same socio-economic family situation and that the schools needed to try harder with my brother.

Little by little, life stabilized. The intense drive lead my parents to forgo the new furniture, the new car, and new clothing, and live instead with the donated office furniture we had in our living room and the donated clothes that made me an odd duck in high school. The temptation was there, as many other refugee families began arriving, working and buying new things. But my parents were determined that their children deserved the best life beyond the material, and high expectations in ourselves was a given. It was a surprise to many when we bought our house two years after arriving. It was a surprise that I attended University of North Dakota, four years after landing in Fargo. In the meantime, my mom clipped coupons, shopped at garage sales and curbed our enthusiasm at the new style of clothing or electronics. The focus was on bettering ourselves by speaking the language and receiving the best grades. They believed that we, as well as our children, deserve the best world had to offer us and that started with the language, education, and then achievements. There were several opportunities for my parents to leave North Dakota, but they chose to stay for the sake of our stability.

Pride had a lot to do with it. My father instilled in me the pride of carrying the millennia-old DNA of a survivor, a fighter, and a leader. He began creating his metal embossing Armenian artwork the very first year of arriving to United States. His first piece of a metal Armenian Khatchkar (cross-stone) was gifted to the Evergreen Methodist Church that helped us. In this country, he could create Armenian and religious pieces, unlike the portraits of Lenin and Soviet themes he was forced to make in Azerbaijan.

My father worked a 12-hour shift, ate, and then went into the basement to pound out his Armenian-themed repoussé. My mother’s paintings and bead work also brought the Americans around them to appreciate the Armenian culture. The Armenian identity didn’t come to me organically, growing up removed from the center of Armenian culture in Baku. My parents not only made us survive physically, but tried their hardest to make us survive intellectually and culturally. These lessons at the dinner table, of our history, our arts, the pride in the generations that came before us came from my father, and in many other ways from my mother.

She and I butted heads throughout my teens and early twenties. Growing up in North Dakota, social expectations and culture was a confusing and painful time for a young woman who was among a handful of Armenians in a group of American friends. She taught me by example that the pride in the Armenian woman, pride in myself, is what defines me and no Feminist book can teach me that. All those things shaped the work that I do and the person I am today. However, this Armenian culture often clashed with the Armenian community in United States. We were removed from it geographically, and in many ways culturally. Until I moved to the East Coast, the Armenian- American culture was so distant from us, yet we were intensely conscious of the lack of awareness within the diaspora of Armenian refugees from Azerbaijan in the United States. One of the very few Armenian college scholarships that answered my application was located in Los Angeles. In response to my request they requested a photo for proof of my “Armenian-ness.”

My parents live and breathe what many try to verbalize, to identify, to define – their Armenian culture, their Armenian pride, and their Armenian identity. My parents’ drive to create, to improve, to grow cannot be beat out of them with violence, hatred, hunger, cold and discrimination, whether from Armenians or non-Armenians. This same drive and story is replicated and multiplied over and over again by many Baku Armenian Americans who are unheard and unseen living in all corners of this country. By honoring my parents publicly, I honor them all.

To my own parents, I thank you both for the sacrifices you’ve made in the prime of your life, for all the countless times you thought of us and never of yourselves, and for the betterment of our family and of our people through your art, your storytelling, and your love. Everything I do and will continue doing, whether it’s in my personal or public life, is because of the people you are and the way you raised me by example.

I love you.

Source: Armenian Weekly

Link: This New Year, I Thank You for Saving Us