Special to the Armenian Weekly

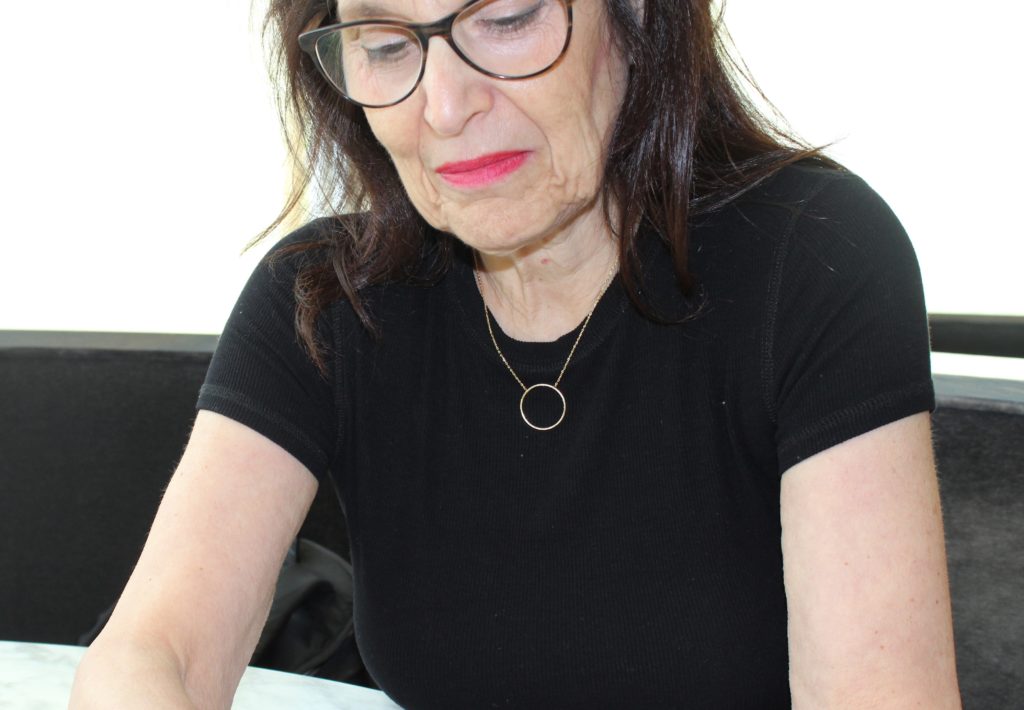

I met with Leslie Ayvazian on a Thursday afternoon in a hotel in Koreatown called The LINE—right in the heart of LA. Before we sat in a crescent-looking booth at the Commissary, Leslie was able to sense patterns about me, it was only our second encounter. A true, fervent, playwright had the aptitude to pick up on things others aren’t equipped to notice. During our conversations, the crescent booth became a full moon; it was as though eye-to-eye human interactions existed again. Leslie’s creative expressionism portrayed the industrial architecture of the hotel’s building.

Ayvazian is the recipient of the Roger L. Stevens Prize and the Susan Smith Blackburn Prize for “Nine Armenians.” Her latest play, “100 Aprils” is the epitome of back-and-forth of surrealism and realism. The play makes you think and re-think. Just as a spiral moves outwards, your perception of the play creates your very own thoughts based on true, historical foundation: the Armenian Genocide.

Directed by Michael Arabian and featuring a cast of five, “100 Aprils” is the triumph of the truth, universally explained. Throughout the play, as a viewer, the totality of the human mind experiences the raw condition of post-genocidal trauma.

In our conversation, Ayvazian opens up about her career, her experiences as a female in the theater industry, and her latest work.

Below is our conversation in its entirety.

***

Lori Sinanian: Under what circumstances did you write the play “100 Aprils?” After watching the play, the setting seems to tell the story of the genocide by universalizing it. It feels emotionally-driven, enabling the entire audience to resonate with what’s right in front of them.

Leslie Ayvazian: Well, I wrote it for the Centennial [of the Armenian Genocide]. I mean, I knew that it was coming up and I needed to write another play. The time had come to write another play.

Everything I do is in one way or another based on my childhood, which is the childhood of suffering from watching my parents suffer. Every time I have a platform, I come back to that story [of the genocide]—it is not unusual for me to tell the story in one way or another.

For the Centennial, I decided I will do what I would to come back to L.A. and be part of what was being experienced here—that was my goal. I started two years before the Centennial. I started doing readings in my apartment. I would invite people over just to listen to it. Also, both my parents had passed away, so I felt that I was able to write more into the truth of our life, which was the anguish and suffering of our lives.

In “Nine Armenians,” the happy side of our lives was emphasized: My parents were alive and their brothers and sisters were alive and all of them came to this. I had dancing in it, I had back-and-forth “Yavrums” and “Anoushings” (terms of endearment). This one, “100 Aprils,” is closer to the truth of my life—the enormous sorrow of my father, who was broken by the genocide. So were his brothers…broken.

My father always lived a version of life—he didn’t live the fullness of his remarkable intelligence; not the fullness of his remarkable artistry. He could draw—he drew in the margins of his notebooks—and he could write. He wrote novels, he wrote articles, he wrote for encyclopedias, but mostly, he ran the periphery of sorrow all the time, as did my grandmothers, as did my grandfathers. That was the atmosphere. For me, a woman turning 70, that was my generation. I always felt the responsibility to try to write it somehow, to make it better for him, to make it better for my grandparents, to somehow ease their pain—that’s a huge responsibility as a grandchild and a child, everybody in my generation felt that, “How can I help you? How can I make it better for you?” And then essentially you are defeated. I was defeated for my father, he literally yelled “No!” in his last breath. That is the truth. He wasn’t ready to die because he was still waiting to live-which is a line from the play. I have conjured different ways of talking about the genocide all my life, as have my sisters.

L.S.: When I entered the venue, I assumed that the first floor is where the play was going to take place, later to learn that I was wrong. One of the men in the room approached me and asked “Oh, are you here to see “1,000 Aprils?” I questioned the title, as it sounded unfamiliar. I then made the connection and thought to myself, “Man, with the significance the name of the play holds, let us hope it is not a 1,000 years that we’re still demanding universal justice for the Armenian Genocide.”

L.A.: [Laughs] Maybe I should change it. Because for Armenians, it does feel like 1,000 years. The number, to Armenians, is just an abstraction, because the day it started it was an unspeakable horror, and that can’t be quantified. My first Armenian play was named “Nine Armenians” with the attempt to quantify. I’ve put numbers in both titles and what I wanted for “Nine Armenians” when it ran at the taper was I wanted the marquee to have the word Armenian in it, and I wanted them to be identified in a number. This is nine of them, you are now going to meet nine of them. Back then you could have casts of nine. Since then, for economic reasons, you need smaller casts.

L.S.: How have your shows at the Rogue Theater been thus far post-opening night?

L.A.: Things continue to surprise me about the experience of being in Los Angeles while doing this play. It is emotional for me to do a premier of a play, just to hear it, because plays are meant to be heard—they are not meant to be read. So when you hear it for the very first time, it is a very important and significant experience of…does it sound like how you imagined it would sound? Are you learning things from that? Is it different, and therefore, better? What is it? But also, having Armenians in the audience, that just matters to me. It matters to me because I know they’re there. Without looking at the reservations list, I know when the Armenians are there, because they respond differently than other people in the audience. They respond to things people who aren’t Armenian don’t respond to. I know right away, in my first entrance, when I pulled the lavash out of my purse, I know what those laughs are. And the effect on me, to know they’re there, literally lifts me up.

I wrote this in the name of my parents and my grandparents, and it makes me feel like they’re there. They have all now passed away but I feel very much in communication with them, still, I speak to them and pray to them, and I wonder how they would feel about this play and I hope they would feel open-hearted and proud… I think they would. But to have the Armenians there feels like having family there, and it has had more of an impact on me that I even imagined.

Once I establish that there are Armenians in the audience, I have a kind of a raft I float on through the whole play because I know that what I’m saying is familiar to them, that I’m not teaching them—I’m just sharing with them. And that’s a different feeling. I don’t write plays to teach people. When I’m in an audience, I don’t want to be taught, I want to figure out what I’m experiencing and I don’t go to the theater to be taught—I go to the theater to have my heart opened so that I can have my own lessons there. This plays goes out on a limb and really does put in information—a lot of exposition about what we experienced—and I had to find a way to make that theatrical and that is why it took me five years. I had so much information to pull from, and you have to sort through what you are actually going to say. Things that were full pages are now just a couple of lines, so experiencing this play with an Armenian audience is giving me, I think, the best premier I can have. I have my tribe, and it helps me do something that’s very hard.

I didn’t expect to be in this play. I expected someone else to do the role, but John Flynn (one of the cast members) needed me to do it. He saw me do the reading and he knew that I carry the world of it in me. Performing it is one thing, writing it is another. When you write it, you are objective. When you’re in it, you become subjective, and that’s a big bridge to cross when you’re doing it for the first time.

L.S.: I believe that those are two different kinds of perceptions as well: performing it and writing it.

L.A.: Yes, exactly. They really are, and they require different parts of your brain. I had to spend a lot of time evaluating the script, making notes in the back of my head, and then trying to also inhabit the script. So the rehearsal process was vigorous to say the least, but now that we are actually running, I feel very much a part of it. I’ve come to trust the script.

The play is 87 pages, it’s 75 minutes, and it’s five years in the making, so it’s been polished like a jeweler polishes an opal. I really had thought of every single word and how they all start here and end there and I think it’s a complete journey. I’m proud of the play. It was a lot of hard work. It’s hard-hitting, but it’s a family, they are a family, and I think you sense that and they have a journey and everything in it is true.

L.S.: It takes a lot for someone to say that they’re so proud about their own play. I think feeling that about your own play is the most satisfying statement because it justifies your abilities and talents—being happy about your own creation, it brings it all to life.

L.A.: Amen… And that’s especially true for women, I could go off on a whole thing about that…

L.S.: What is it like to be a woman playwright? I was wondering if you can tell me more about that, being a woman in this sort of creative industry.

L.A.: What it is to be a woman playwright; that is very real for me. The subject matter we choose to deal with and the entrance we have, there are still not that many women playwrights, women directors, women designers—it’s still an unbalanced field. Yes, this is the world I live in right now, in which I have always lived. The world of consciousness around the inequality of the female experience and the male experience. I have a wonderful husband and a wonderful son and I don’t bash men, but I am very, very sensitive and very alert to the different systems that we live under.

Ever since I was in my 20s, I had headed up writing groups just for women, once a week, and I’m turning 70 this summer! Just so that women can get together and write, and discover, and investigate, and listen to each other’s voices. I have been extremely sensitive to the language that is used around women. I just launched a series at Columbia called “Women in language” where I invite women in their 60s, 70s, 80s, and 90s, to sit on stage and talk about how they have prevailed in this business to the younger people who are my students—to the women in their 20s and 30s who ask questions. I start out with a list of words that apply to women and then how do we cope with them: Aggressive, abrasive, abusive, assertive, ambitious bitch, ball-buster, castrator—I go all the way from A-Z. I have collected over 450 words that are used just for women and they are used in the world all around us, we use that language for ourselves, and that’s the saddest thing—that we define and accommodate the language of diminishment. That’s what I try to look at squarely, respectfully, and name it. If I know someone is speaking to me in a way that they wouldn’t speak to a man, I call it, I say it, I point it out. I say, “If you were speaking to a man, how would you say that sentence? Tell me the truth.” I go through life with this ultra-sensitivity about the language of diminishment and I try to substitute words for those words. I’ve been called aggressive so many times. Men can be aggressive, but it doesn’t have the same sphere…

L.S.: Right, it does not have a negative connotation.

L.A.: It definitely does not, it’s a plus for a man…

L.S. & L.A.: [Simultaneously] And a minus for a woman.

L.A.: If you’re calling me aggressive, then what I need to do in my mind is that I need to think: Maybe the word is actually courageous, maybe the word is destined, maybe the word is good example, maybe the word is heroic, maybe the word is skilled or prepared, maybe the word is hungry. Those words can be used instead of aggressive, assertive, abrasive. Those words are not used for men in the same way. What I’m telling you is, I’m sensitive. I hear the language and as soon as I recognize that it is trying to do something to make me smaller, to make me less intelligent, to make me feel that I’m behaving badly, I re-frame it.

I am a work in progress of a woman who is looking for true liberation from the language of oppression, which is the language we all speak and at this age. And I’m going to say it over and over again, because I cannot believe I’m turning 70 in four weeks, and yet I’ve never felt more empowered, I’ve never felt better looking. I’ll say it, straight out. I walk into a room and I have presence and that presence doesn’t have anything to do with any of that. I am keeping the face of an aging woman, I am keeping the neck and skin of an aging woman, and I am hoping that what is there in me shines past that and then I can be a true crone with full pride—that I am serving as some example for younger women to identity what is keeping you back, what is keeping us back. Under any circumstance, in the arts, as a playwright, under any circumstance, it is the same battle. Just identity, what is the language that is being used for you, and help you change that so that the dialogue you have with yourself is positive and allows you to access your intelligence.

Anyone who is pushing aside our intelligence needs to be addressed, so that we can cling our intuition as intelligence. Women are intuitive, men are intuitive too, but they don’t allow it and they haven’t been raised to allow it. Women have innate intuitions and innate instincts, we have children inside us, we know these secrets, we know this breath of life, we need to defend it in ourselves. When we are together, we can be tribal when we are together. I love that word: tribal. I love that ancient women in ancient societies truly raised children as a village. What existed when we lived in the time of the matriarchies, were peaceful environments. They were about life and instincts and death and earth. We have lived away from that and the planet has suffered so that’s what a big deal I think it is, that when women write what it is inside themselves, the play writes itself. Sadly, this terrible place of living with misogyny and racism, things have hurt us, hurt the planet, hurt the universe, hurt God, and it’s up to us to claim ourselves and we could do that by becoming alert to what we’ve gotten used to.

“Hey Bitch!” you would never hear me say that. You would never hear me call another woman a bitch. Never. I will not co-opt the language of the patriarchy. I won’t make it mine because all that does is give me swagger—and swagger isn’t power. Power is authenticity (points at her stomach to put focus to her organs) It’s not here (as she points to her physical features), it is not attitude! It is authenticity—you hold that and you weld some power. So, that’s how I deal with it, every day. Every day I confront what it is that is slightly different because I’m a woman.

L.S.: Even through your portrayal of words, I feel it, without needing to experience it. I feel as though modern-day matriarchy is evident in a sense that women know it exists. Life for women, it’s challenging, but we’ve becoming prone to defeating those challenges, we seem ready for the challenges in life merely because the determining components of everyday-life for women has raised us to be ready for whatever comes forth.

L.A.: Yes. I mean, good for us. Life I believe is an athletic event and we need to be athletes—We need to train and be athletes. That’s the other thing I’m an advocate of. When I realized that I was hitting 70, that I was postmenopausal, I realized that there is a lot of language around about what happens to a woman after menopause: the kind of giving in and settling down kind of thing. What I did is, I just accelerated—I just decided I’m going to be as disciplined as I can be, so I can have as much energy as possible to I can just push back the clock. Because now is the time I’m meant to be alive. I want my 70s to be my most “alive” decade, and I think it will be.

L.S.: Feeling so certain about 70 being your most alive decade yet, what can you tell your 20-year-old self?

L.A.: My 20-year-old self was in the 60s and the 70s. I was pretty, and didn’t know what that meant. I was pretty so I didn’t think I was smart because my sister was smart. I didn’t think I was athletic because my other sister was athletic. We each had a tag and we each had a title and being pretty was mine and I didn’t know how that served me and I got in a lot of trouble. I rode motorcycles, I had a lot of boyfriends, I did not believe I was smart and I suffered. I didn’t join the women’s movement, I saw women as competitors. But you know something, I wouldn’t say anything to that girl, because I needed to have that to have this. I was a product of my time, I was a hippie, I was outside the box, uniformed, risky, good hearted, but confused.

Yet we learn our lessons, don’t we? Hopefully, life is about gaining wisdom, and I don’t think I would lecture that young girl. I have this show called “Mention My Beauty” which is me, one person on stage standing at a music stand, talking to the audience about my life. I actually read the story of my life to the audience. There are no production values and you call it a play. I don’t call it a reading, I don’t call it a cabaret act. It’s a play and the audience just sits there and looks at me for an hour and 20 minutes and imagines the whole thing in their mind.

I tell them what it was like, riding motorcycles in my 20s and having basically no purpose in living with a great amount of danger. I tell them what it was like to join VISTA and go to the south end of Columbus, Ohio, and teach African American kids. I had no idea about their culture and I was trying to teach them to be white. I was useless. What it was to be confused, lost, uninformed, and competitive with other women and how each decade has changed for me, and what it is to prevail. That’s my show.

Now I’m going back to do a one week workshop at Dartmouth through New York Theatre Workshop the first week of August. I’ve been invited to work this play [“Mention My Beauty”] for them and I’m thrilled about it. It’s starting to gain traction and ultimately it will be a book that I will sell.

Do you ever come to New York?

L.S.: I’ve been before, only twice. It’s an amazing place to be. I would love to go back one day.

L.A.: You really should come back. I will take you places, I will show you things. It’s an extremely exciting city.

L.S.: I have so much I need to see, so much life I still need to experience.

L.A.: New York is a great place do it. I mean, it’s also harsh, it’s relentless, it’s brutal.

L.S.: I think I need that.

L.A.: I do too. I think we all do. If you want to challenge your life, not everybody does, but if you’re an artist, you’ve got to rub up against the sandpaper, you have to figure out who you are, because that’s what you’re giving people. You’re giving your information, your intelligence, your spirit to the world, so you have to be very ready to do that—you’ve got to become fit and I think that happens through challenge.

That’s one of the reasons why I said yes to John Flynn, and he said yes when I asked him to do the role. That was a challenge for him. I mean, he’s the artistic director of the Rogue Machine, he has a wonderful reputation, he’s a hard-working guy, and he took on this hard role after not being on stage for 30 years. That’s a challenge! and he decided to do that in his thirties. Since we both made that leap, we feel like a married couple on stage.

L.S.: What is a maxim you live by?

L.A.: “To be wide inside.” It’s a provocative thing to say, you’re not sure what it means, but that’s good too. Think about it. Contraction limits, wideness expands your own intelligence and allows you to access your intelligence. It’s a job to be available to yourself, it’s worth putting your time and thought into it.

L.S.: The word “wide” to me is very abstract as well, and it’s not limited either, so yes, wideness allows you to access intelligence, but the overall self… The inner-self.

L.A.: The inner self, to fill out to the margins of who you are.

L.S.: Or expand from the margins!

L.A.: Or beyond! I mean, once you get here, there’s no place to go but out here (pointing outwards) and then you can access everything around you, and give to it. I think the key to life is giving and that’s what I think artists really want to do. A lot of artists aren’t very good business people. Some of them are, but not necessarily. Artists want to give what they have: Here’s my drawing! Here’s my music! Here’s my painting! Here’s my language! I hope it has some impact on you. Thank you for listening, thank you for looking, thank you.

L.S.: It’s a reciprocal experience, the want to share.

L.A.: It is, and it’s a wonderful way to go instead of just taking. What can I take? What can I have? But what can I give? And I really do think that’s why actors work for free, hard jobs. They work for free because they’re out there giving what they’ve got, and ultimately, that’s what makes them feel alive. It’s the rock concert of life.

L.S.: I concur. I believe that art is a conversation starter. With art, it is always about giving, never about taking. The only thing you take from art is the experience, which is priceless and irreplaceable. Life is an unfolding experience—an educational lab.

L.A.: Yes, it is, and that’s what we have to aim for. It’s a choice. We get to make choices in this life, sometimes, some of us are luckier than others.

L.S.: But the choices we don’t get to make, that makes it a challenge and I don’t think that’s unfortunate at all.

L.A.: No, I don’t either. But I don’t think the game is always fair. People are born into situations that can be too challenging. It’s how we rise up—it’s always how we rise up. It’s not about getting knocked down because we all do. None of us are living in the Garden of Eden.

When you rise up, you have a shot at living the challenge of life and giving to it and making a difference even on a small level— a day to day small level. That is what I think I do, sometimes the things I do is not grand, it’s not important

L.S.: Even getting out of bed can sometimes be challenge.

L.A.: I wrote a short film about that. The process of getting out of bed. It’s called “Every Three Minutes,” and it’s only three minutes long. It ran on Showtime and even won an award. The fascinating smallest moments of life can hold all of life. If you can take a picture of something authentically, it has the whole world in it; it doesn’t always have to be the major things.

Thanks for coming to my show.

L.S.: Of course.

***

“100 Aprils” will run until July 16 (Mondays, Saturdays, and Sundays) at the Rogue Machine in the MET Theatre (1089 N. Oxford Ave, Los Angeles, Calif. 90029). For more information and for tickets, visit: https://roguemachine.secure.force.com/ticket#details_a0N2A00001oiafnUAA

Author information

The post To Be Wide Inside: A Conversation with Playwright Leslie Ayvazian appeared first on The Armenian Weekly.

Source: Armenian Weekly

Link: To Be Wide Inside: A Conversation with Playwright Leslie Ayvazian