An Interview with Andrew Moore, the Director of Development of the HALO Trust

Moore: ‘Karabagh is one of the Easiest Places in the World for HALO to Conduct its Work’

WATERTOWN, Mass. (A.W.)—Twenty years ago, the late Diana, Princess of Wales, was famously photographed wearing body armor with the words “The HALO Trust” written across the chest as she entered a minefield in Angola.

Twenty years ago, the late Diana, Princess of Wales, was famously photographed wearing body armor with the words ‘The HALO Trust’ written across the chest as she entered a minefield in Angola. (Photo: The HALO Trust)

And just like that, the landmine issue shot to international prominence.

“That was a key moment for landmine clearance generally, because it brought the world’s attention to this humanitarian catastrophe that was happening in so many countries around the world,” admits Andrew Moore, the Director of Development of the HALO Trust.

The minefield that Diana visited in Angola is now a thriving suburb with houses and a college. “There is absolutely no trace now that there was ever a minefield there,” Moore says.

The HALO Trust is the oldest and largest landmine clearing organization, operating all around the world. It was established in 1988 and its first program took place in Afghanistan as Soviet troops withdrew from the country. While the organization employs around 7,500 people across the world, the HALO trust is a British and U.S. registered entity with significant funding from the British and American governments.

Prior to becoming HALO’s Director of Development earlier this year, Moore was the organization’s European Regional Director for seven years. “Karabagh was one of my programs, so I would visit there three or four times a year. It’s a place that is very dear to my heart,” he explains.

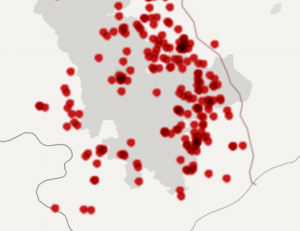

According to HALO, there have been about 370 civilian casualties in Artsakh since they began recording the figures in 1995. (Map: The HALO Trust)

HALO first started working in Artsakh in 2000. “We had conducted some work with training local capacity in Karabagh prior to that, but there were a variety of issues. By 1999 we got an appreciation of the size of the landmine problem there and realized that it was significantly greater than we had initially anticipated,” Moore explains.

According to HALO, there have been 370 civilian casualties in Artsakh since the organization began recording the figures in 1995. “Per capita, given that Karabagh has a tiny population, it has one of the highest accident rates anywhere in the world,” says Moore. “It’s up there with the conventional countries, which we expect to have landmine problems, like Cambodia and Afghanistan.”

According to HALO’s figures, a third of the recorded incidents in Artsakh have involved children.

Since officially entering Artsakh, HALO has employed as many as 280 local residents, who, among other things, have been responsible for conducting the clearance. According to Moore, HALO currently employs around 220 locals. “We are clearing mines that were left during the war by both sides,” he explains.

Anti-personnel mines—designed to be initiated by individuals standing on them—and anti-vehicle and anti-tank mines—designed to be initiated by vehicles driving over them—were used during the war of 1988-1994. In the wide, fertile, open valleys of Artsakh, the anti-tank mines were used extensively and have been the significant cause of the casualties.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nmJnTkj2Mok]

Although HALO Trust has secured substantial USAID funding for de-mining Artsakh, that funding is confined to territory within what was once the Soviet oblast of Nagorno-Karabagh, for what Moore assumes are “political reasons.” “We cannot use U.S. government funds to clear minefields in areas adjacent to [the Soviet oblast], but that are still part of Karabagh, or Karabagh-controlled territory. So, we can’t, for example, use them in Lachin,” he explains.

Artsakh de-miner Marina Barseghian is a mother of six children. Her eldest son is a policeman and her eldest daughter is a nursing student. (Photo: The HALO Trust)

Of the minefields within what was Soviet Nagorno-Karabagh, HALO has cleared about 96 percent of them with U.S. government funding. The majority of the remaining minefields are now in what Moore calls the “adjacent territories” and the organization has been seeking private funds to clear them.

Two and a half years ago, a foundation based in the U.S. with no Armenian connection, who had funded HALO on a relatively small scale previously, became interested in significantly increasing its investment in landmine clearance. Even with the substantial resources available, in somewhere like Cambodia where the problem is enormous, it would still be making a relatively small dent. “They were interested in somewhere where they could show leadership and somewhere where they could really make a difference,” Moore explains. “We said that Karabagh was the place to make that huge difference. They have since given us grant funding.”

HALO has estimated that the clearance of the mines in the remaining territories will cost $8 million U.S. dollars. The foundation, which has wished to remain anonymous, has committed to donate up to half of that on a match-funding basis. “For every dollar that we raise, we get a dollar matched from the foundation,” Moore says.

In July 2015, the HALO Trust dispatched their first all-female team of de-miners to Artsakh. (Photo: the HALO Trust)

So far, the HALO trust has raised a million of that $4 million dollars and are seeking to raise the remaining $3 million over the next couple of years, in order to make Artsakh landmine free by 2020.

The organization ran a small crowdfunding campaign last year—what Moore believes to be the first crowdfunding campaign ever conducted to clear a minefield anywhere in the world. With that, HALO raised the funds to clear one minefield in Lachin—a mission that is currently underway.

HALO’s crowdfunding efforts really took off though, when the organization partnered with U.S./Armenia-based OneArmenia, which wished to make HALO the focus of its first campaign of 2017. “Although we are a large organization in many respects, in terms of communications and especially the work that is required for crowdfunding, it’s all very new to us,” Moore admits, “so, working with a partner—especially one that is so engaged—was very appealing to us.”

Moore says that he was incredibly impressed with the enthusiasm, inventiveness, and dedication of the people at OneArmenia. “They were a fantastic partner to work with and did a wonderful job bringing the campaign alive. They worked really hard to achieve the goals and now, the de-miners who will be clearing there are being trained as we speak and will start their clearance any day now,” he says.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GTdbzzhNnCc]

Most of donors to the joint crowdfunding campaign were Armenian—from Karabagh, Armenia, and the worldwide Armenian Diaspora—Moore explains. “We also got donations from non-Armenian sources. People are interested in the region. People are interested about Armenia and Karabagh,” Moore says.

A majority of the million dollars that HALO has raised for Karabagh so far has come from non-Armenian sources.

However, for most of the countries that fund landmine clearance and for most Western donors, Karabagh is politically contentious. “That is our biggest obstacle,” he says.

Though funding has been one of the key challenges from the outset, one thing that has not been a challenge for HALO is actually working in Karabagh itself. “We have absolutely excellent cooperation with the [Artsakh] authorities. They allow us to work and there is no interference in what we do. Of course, everything we do is coordinated with [the authorities]. They trust us and we have a longstanding relationship,” he explains.

According to Moore, from an operational perspective, Karabagh is one of the easiest places in the world for HALO to conduct its work.

When asked why he thinks that is the case, Moore says that one reason may have to do with trust. “There is no suspicion or distrust in Karabagh. Very often, in countries that are emerging from war or have had longstanding wars, people are suspicious of our motives and why we’re there. That isn’t really the case in Karabagh. We have extremely strong support at all levels and it’s a very welcoming environment altogether,” Moore says.

In a global first, the HALO Trust launched a $30,000 crowdfunding campaign to clear a minefield in Myurishen village in Artsakh. Photographed are Mikhail and Zabella Merjumian of Myurishen. (Photo: The HALO Trust)

It has not always been easy to work in the region, however. There have been major security challenges, especially since the 2016 April War, that HALO had not encountered previously in Artsakh. “When we are working closer to the Line of Contact (LoC), we have to be more mindful of that. We’ve had instances where we have had to temporarily suspend work on minefields close to the LoC. That’s been a real challenge in recent years,” Moore explains.

One of the other main challenges the HALO Trust is constantly up against is what Moore calls “Azerbaijan’s objection to all activities regarding Nagorno-Karabagh.”

To help overcome these challenges, this month, Boston-Armenians Nina and Raffi Festekjian, the Co-Chairs of HALO’s “Safe Steps for the People of Karabagh” campaign, will be opening their home and hosting a special fundraiser to help complete the de-mining in the small, but growing, Armenian republic. The Festekjians have become the figureheads for HALO’s Karabagh fundraising and are what Moore describes as “great advocates” for the organization’s work. “Raffi and Nina instinctively connect with what we’re doing and the reasons why we’re doing it,” he says.

According to Moore, the purpose of the June 10 fundraiser is two-fold. “We obviously want to raise money, and every dollar raised that evening will be matched by our donor and go towards the $4 million,” he explains. “In addition, we have five exclusive photographs of Karabagh taken by [famed Armenian-American photojournalist] Scout Tufankjian that will be auctioned that night. We’ve also had a donation from Zorah Wines, which we will be auctioning off. These are award-winning wines that are not currently available in the U.S.—or certainly not in Massachusetts.”

Following the Boston event, there is a second fundraiser planned in New York on June 15, which will be hosted by Sandra Shahinian Leitner—a longtime HALO donor and supporter.

There is no doubt that HALO’s work has hugely aided Artsakh and its people. A recent USAID evaluation estimated that of the population of around 150,000, close to 125,000 people have directly benefited from the work that HALO has done since 2000.

Nor Maragha village school in Artsakh’s Martakert region was built after HALO had cleared the area and returned the land back to the community in 2006. (Photo: The HALO Trust)

“The impact has been huge,” Moore says. “For example, the gas and water supplies to Martakert town were put in through minefields that we cleared. There have been irrigation channels and water supplies to many villages that have been installed. Huge areas of agricultural land has been freed up to be used for cultivation of wheat and grapes,” he explains.

The impact of HALO’s work in the country is manifold—from stopping people from being killed and injured, to allowing land to be used productively, all while employing 220 Armenian staff. “We’d like to increase that to 300 if we can raise all of this money,” Moore says. “That provides investment in Karabagh.”

Around 90 cents of every dollar collected is spent directly in Artsakh—on employment, supplies, fuel for the vehicles, food for the de-miners, accommodations, and so forth.

“As you know, Armenian families are extended families—it’s not like we’re supporting typical American or European nuclear families; we’re supporting grandparents, brothers, sisters, grand-kids… generations, really,” Moore says. “This leaves a huge impact.”

Source: Armenian Weekly

Link: Twenty Years after Princess Diana’s Iconic Walk, a Landmine Free Artsakh is in Sight